Bottle Rocket and Fargo: How Wes Anderson and the Coen brothers brought ‘peak quirkiness’ to cinemas 25 years ago

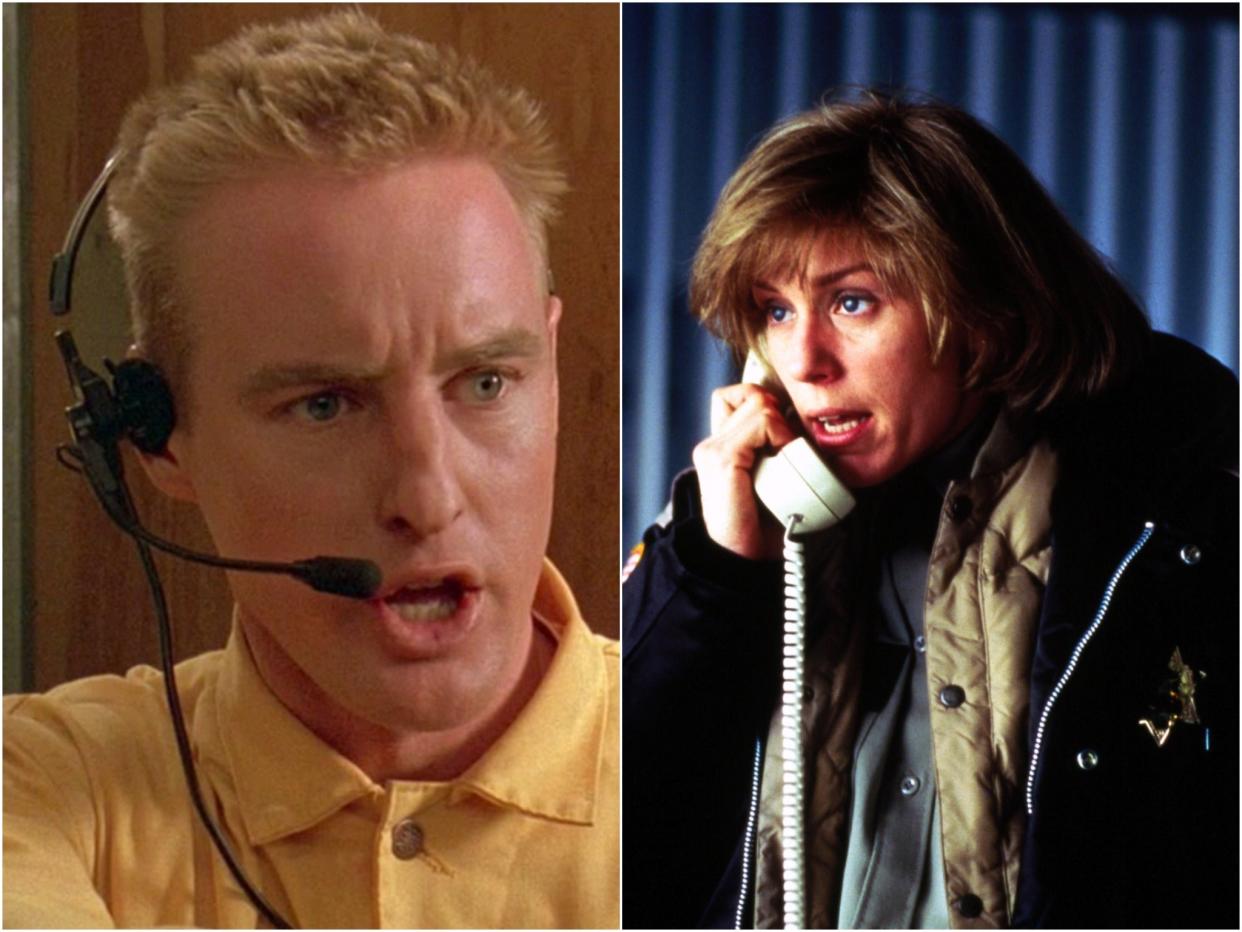

Owen Wilson in ‘Bottle Rocket’ and Frances McDormand in ‘Fargo’

(Sony, MGM)Two movies, released two weeks apart, but connected by an almost overpowering quirkiness and a fascination with people on the fringes of society. On 21 February 1996 – a quarter of a century ago today – 26-year-old Wes Anderson’s feature length debut, Bottle Rocket, tip-toed into some 30 cinemas around the United States. Just over a fortnight later, on 8 March, the Coen brothers put out their sixth film and their first mainstream hit, Fargo.

That off-kilter sensibility – a wry laying bare of the absurdities that ripple through everyday life – is one of the qualities uniting the films. And it made them part of a wider 1990s trend. Independent cinema in America, having had its “Smells Like Teen Spirit” breakout moment with Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs in 1992, was by the latter half of the decade tilting in an increasingly idiosyncratic direction.

Lovable weirdos were popping up everywhere. In music, self-proclaimed “creeps” and “losers” such as Radiohead’s Thom Yorke and Beck woke up to discover they were pop stars. Slacker culture had pushed into the mainstream the idea of apathy as a form of political resistance. Fashion was likewise going its own way, with oversized cardigans, and vintage dresses paired with Dr Martens boots de rigueur, and stars such as Kate Moss and Gwyneth Paltrow turning up at premieres without make-up. The same values were being celebrated on the big screen. From the hapless store attendants in Kevin Smith’s Clerks to Vince Vaughn and Jon Favreau’s failing actors in Swingers, outsiders were in. And no filmmakers were better positioned to take advantage of that fad than Anderson and siblings Joel and Ethan Coen.

This wasn’t necessarily new. As far back as the 1970s, there had been cult curios such as Hal Ashby’s Harold and Maude – about a romance between a man in his early twenties and a woman nearing her eighties – and Terrence Malik’s lovers-on-the-lam masterpiece Badlands. The difference is that, by the Nineties, these tendencies were achieving a critical mass. And, amid grunge and the alternative scene, they were suddenly in tune with the wider culture. The hour of the outsider had arrived. Offbeat was cool. “[There] was a coming together of various elements that saw independent films blossom in the 1990s,” says Phil Edwards of movie blog Live for Films.

In addition, more people were going to cinemas, so more films were needed to fill them. In 1990, there were 97.4 million cinema visits in the UK, according to the the UK Cinema Association. By 1996, that had shot up to 123 million and would reach 139 million by the end of the decade.

Filmmaking technology was undergoing a major shift, too, with the advent of digital cameras. “That meant low-budget films could be made and still look good,” says Edwards.

Bottle Rocket and Fargo were a case in point. Not only did they look similar, thematically they had a great deal in common. Both are about inept crooks – exploding the myth, so beloved of cinema, of the master criminal. In Bottle Rocket, actor siblings Owen and Luke Wilson – Owen having also helped Anderson write the script – play friends and would-be robbers (the title refers to the cheap fireworks Owen Wilson’s character constantly sets off). The tragicomedy flows from their incompetence as they try and fail to pull off a series of heists.

Fargo, meanwhile, tells the story of equally flailing used-car salesman Jerry Lundegaard (William H Macy). He gets in over his head when hiring a duo of bungling thugs (Steve Buscemi and Peter Stormare). Their mission is to kidnap his wife (Kristin Rudrüd) in order to extract a ransom from Jerry’s minted but disapproving father-in-law (Harve Presnell).

The hero in Fargo is policewoman Marge Gunderson (Frances McDormand), who investigates the chain of killings the botched kidnapping sets off. But it’s Macy as Lundegaard who haunts you. He’s the spiritual twin of Owen Wilson’s Dignan in Bottle Rocket. Each is living in a fantasy world in which they think crime will solve their problems. Bottle Rocket and Fargo have their moments of silliness, yet ultimately serve as a caution against knee-jerk optimism. Amid the brightness of the humour creep long shadows.

“The Coens were plugging into a current filmmaking trend – the vogue for intertwining elements of crime and comedy in deliberately exaggerated ways that had taken on considerable momentum thanks in part to their own previous work, most notably Blood Simple and Raising Arizona,” writes David Sterritt in his 2004 essay “Fargo in Context”. “Other such films released to American theatres in 1996 include Wes Anderson’s Bottle Rocket and Benjamin Ross’s Young Poisoner’s Handbook, both of which show signs of influence by the Coen approach.”

Another reason Bottle Rocket and Fargo stand out today is that comparatively few movies were being made. Just over 300 feature films were released in American cinemas in 1996, according cinema data site The Numbers. By 2018, that had jumped to 873. Even in 2020, the year of Covid, the total topped out at 329. So even though more people were going to the cinema, fewer films were coming out. And for two significant indie touchstones to be in cinemas at the same time was, in retrospect, noteworthy. Twenty-five years ago, simply putting out a feature was an achievement unto itself. Once a film did see daylight, it stood a good chance of garnering attention. There simply wasn’t an awful lot of competition.

“The 1980s and 1990s was the age of straight-to-video cinema. So many first-time filmmakers could make films on a low budget and sell them for profit relatively easily,” says filmmaker and blogger Amy Clarke.

“Think about Clerks, Reservoir Dogs, El Mariachi, and Sundance film festival. Then came along digital and everyone could make a film. And everyone did…. If you made Clerks today it wouldn’t win awards, because anyone can make that film without money or training. So the 1990s was the golden age of independent cinema, and it came to end by the early 2000s.”

Bottle Rocket and Fargo were each based on true stories – to a certain extent. The Coens told their cast and crew that the events in Fargo had really happened. And the action opens with a title card that reads , “The events depicted in this film took place in Minnesota in 1987. At the request of the survivors, the names have been changed. Out of respect for the dead, the rest has been told exactly as it occurred.”

There were twinklings of verisimilitude in this boast. The Coens had indeed been inspired by the case of a General Motors Finance Corporation employee who committed fraud by manipulating car serial numbers, as Jerry Lundegaard does. In addition, they drew on the tragic demise of Helle Crafts, a Connecticut woman whose husband killed her and disposed of her body in a wood chipper – the grisly fate suffered by Buscemi’s character.

In the case of Bottle Rocket, the inspirations were closer to home. The rooftop heist at the end of the movie was based on a break-in that flatmates Anderson and Owen Wilson staged in their own apartment in Austin, Texas. They’d faked a robbery in the hope of persuading their landlord to fix a draughty window (through which the “robbers” had entered). Just as on the screen, their incompetence tripped them up, with the police immediately clocking their amateurish subterfuge.

With Bottle Rocket and Fargo as launch pads, Anderson and the Coens would go on to be become the masters of American whimsy. Their work could be bleak (No County for Old Men) or strange (Isle of Dogs), hilarious (The Big Lebowski) or ominous (The Grand Budapest Hotel). But they always adopted an outsider perspective and approached the familiar from an unusual angle. And thus they have each, across the arc of their careers, made the everyday seem strange and new. To this day, it’s what unites them as filmmakers.

The Coens, it is true, were already off to the races, whereas Anderson was just starting. And yet Fargo was in many ways a reset for the siblings. Having won acclaim for early films such as Blood Simple and Miller’s Crossing, they had crashed and burned with the 1994 Paul Newman/Tim Robbins grand folly The Hudsucker Proxy, which earned just $2.8m on a $25m budget. Coming through that disaster, they found their true voice – deadpan yet dark, humorous but unnerving – in Fargo. And it would, of course, inspire the present-day Noah Hawley TV spin-off, series four of which stars Jessie Buckley and will air in the UK this year.

For Anderson, it was the beginning of everything. It was also nearly the end – his own miniaturised Hudsucker Proxy. And just like the Coens, who had felt on top of the world going into Hudsucker, he never saw the looming disaster. He naively assumed everyone would love Bottle Rocket.

“I was never more confident in my life when we made it,” he told friend and collaborator Noah Baumbach in a 2009 public interview. “And never less confident when we screened it. When we screened it, that was part two of my life. Up until then, my attitude was like, ‘Just wait until they see this.’ We screened it in Santa Monica AMC for an audience of 400 people. Sitting in the back row with all the studio executives, I began to see people leaving. They were leaving in groups. People don’t go to the bathroom in groups. They’re not coming back.”

The film was a flop, having been pushed by Columbia Pictures from its original late 1995 release date to the dead calm of February where it was correctly presumed it would sink without a trace. Preparing for Fargo, the Coens encountered their own studio resistance, as Warners, spooked by The Hudsucker Proxy, dropped out, despite a relatively puny $7m budget.

Bottle Rocket’s budget was in the same range – $5m – and, if anything, it had the bigger star in James Caan, who plays an organised crime mentor to the inept Dignan. But it would implode humiliatingly, bringing in just $560,000, whereas Fargo earned $25m, five times its production costs and 10 times the total generated by The Hudsucker Proxy.

Fargo was heralded on release as an instant classic. The Radio Times described it as a “modern masterpiece” and Variety praised it as “strikingly mature”. (One dissenting voice was The Independent, which stated that, “in effect, the Coens have written an action film that disregards the basic principle of the genre: that character is expressed in action”).

Bottle Rocket, by contrast, took its time building a reputation. That said, initial reviews were positive. “A confident, eccentric debut about … shambling and guileless friends … Rocket feels particularly refreshing because it never compromises on its delicate deadpan sensibility,” said the LA Times. A road movie that “meanders pleasantly” went The New Yorker.

These kind notices were enough to allow Anderson to continue to have a career and to begin work on 1998’s Rushmore. There, he would find his definitive style of playful camera movement and symmetric composition of shots.

A little of both are in Bottle Rocket. But, unlike everything else he’s made, it doesn’t look like a “Wes Anderson” film. Indeed, it was only in the following decade that it would receive its dues, when Martin Scorsese proclaimed his fandom. Scorsese instinctively got a film that had soared over the heads of so many cinemagoers. It was, he observed, “about a group of young guys who think that their lives have to be filled with risks and danger in order to be real. They don’t know that it’s OK simply to be who they are.”

Watch it today and it’s striking that, for all their contrasts and for all the violence in Fargo, the two films are steeped in a quintessential 1990s capriciousness. Bottle Rocket was filmed in Anderson’s native Texas under aching blue skies, while Fargo, shot by master cinematographer Roger Deakins in North Dakota, unfolds against a canvas of white and grey. But their souls feel entwined. Bottle Rocket and Fargo are about lost people seeking salvation through crime.

But the two films go further in persuasively arguing for boring wholesomeness. In Bottle Rocket, Luke Wilson’s Anthony is constantly pushing back against Dignan’s dreams of becoming a big-time crook (he really is only going along out of loyalty). And in the end, it’s Dignan who goes to prison, whereas Anthony hooks up with Inez (Lumi Cavazos), the Paraguayan chambermaid whom he meets while he and Dignan are on the run. In Fargo, the avatar for good is McDormand’s Marge Gunderson, a competent policewoman and someone who fundamentally cannot comprehend why ordinary people would be driven to evil.

Bottle Rocket and Fargo each also walks a deft line between tragedy and comedy. “We are often asked how we manage injecting comedy into the material. But it seems to us that comedy is part of life,” Joel Coen would say while promoting the film. It is an outlook with which the eternally droll Anderson would surely agree. Half a lifetime ago, Bottle Rocket set him on the road to his current position as dean of American incongruity. And Fargo did much the same for the Coens. How strange to think that these pivotal moments in their careers should occur almost simultaneously and have so much in common.

This article was amended on March 4, 2021. The article originally stated that the Bottle Rocket character Inez was from Mexico, but in the film she says she is from Paraguay.

Read More

The Big Lebowski at 20: The enduring legacy of the Coen brothers' zonked-out cult classic