Blue Ruin by Hari Kunzru review – art monsters

Blue Ruin opens with the protagonist, Jay, delivering groceries to a palatial home in a rich enclave of upstate New York. On the doorstep his customer stands masked; this is happening in the early days of the Covid lockdown. Thus it takes him a moment to recognise Alice, his girlfriend from another life.

Twenty years before, Jay and Alice lived together in London. He was then an up-and-coming Young British Artist, and she an aspiring curator. They had one of those relationships that made people run their names together: Jayanalice, Aliceanjay. Now she is “radiant with the kind of health that’s made of yoga and raw juices and massage and money”. She’s also married to Rob, Jay’s erstwhile best friend and rival, for whom she left him without a word. Jay, meanwhile, is prematurely aged from poverty and the punishing jobs that go with it. He’s sick with long Covid and filthy from weeks of living in his car. “See me, Alice,” he thinks. “Nothing but a ragged membrane. A dirty scrap of ectoplasm, separating nothing from nothing.” She does see him; she calls out his name. A moment later he collapses, struggling to draw a breath.

Alice takes Jay in, hiding him in a barn to conceal him from Rob and the other two members of her lockdown pod. In Jay’s long, fevered days of convalescence, he is haunted by memories of their past.

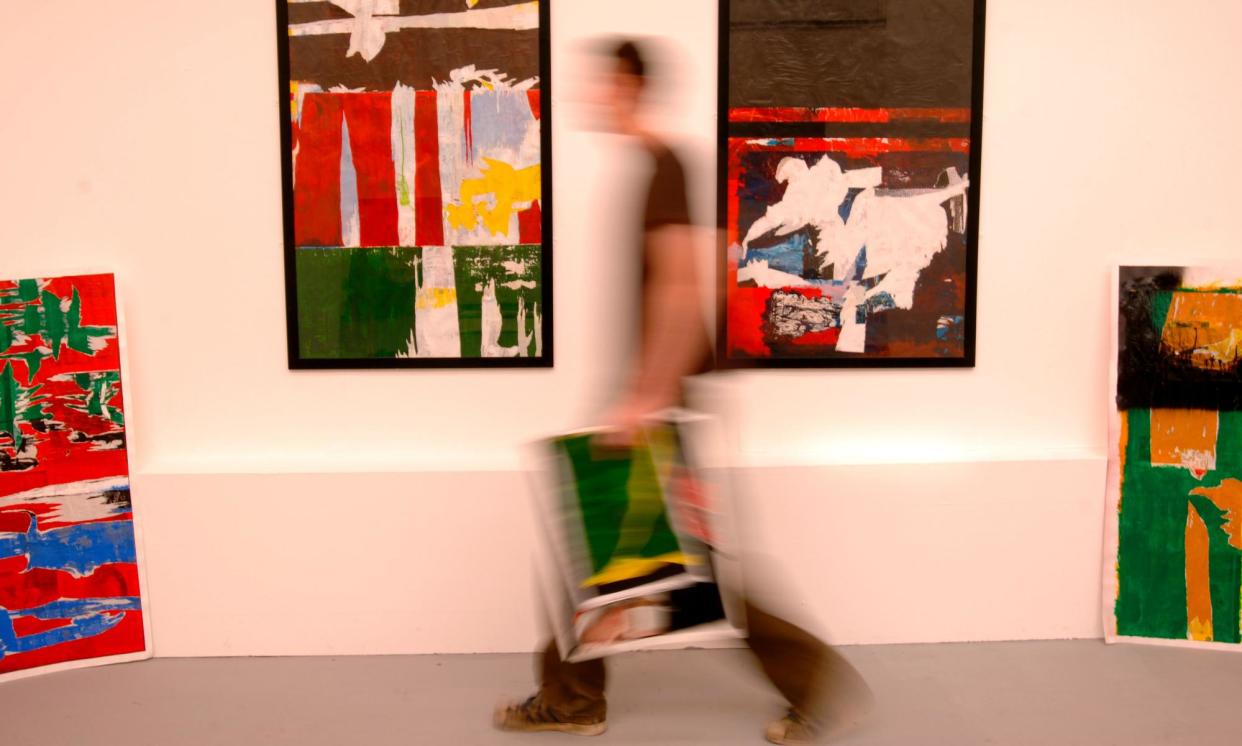

These long flashback sections, which take up most of the book, are what is most remarkable in Blue Ruin. The seamy, drug-crazed, millenarian atmosphere of the 90s British art world, with its intermingled idealism and cynicism, is brilliantly evoked. Here radical artists squat in derelict industrial buildings, but fill them with paintings that pander to the tastes of wealthy collectors; any quest for authenticity immediately becomes just a cannier way to sell out. Not only art but artist is reduced to a commodity. Against this backdrop, Jay and Alice seek solace and humanity in each other, but are ineluctably brought down by demons of past and present.

The British art world, with its intermingled idealism and cynicism, is brilliantly evoked

The use of artworks – a difficult trick in fiction – is especially impressive in Blue Ruin. Kunzru effortlessly makes us see why Rob’s art-school still lifes, “executed with a few washes of watercolour that gave each object real volume and presence”, intimidate Jay and fill him with a sense of his own fraudulence. We feel viscerally why the diagram-drawings Jay makes about his relationship with Alice are an artistic dead end, while his performance pieces are both artistically transformative and personally dangerous.

Kunzru also does a great job at conveying the outsider life into which Jay falls. “I have walked for miles along roaring highways, strafed by lights. I have been chased by feral strangers, who tried to throw me off a bridge … I worked construction during the fracking boom in New Mexico, watching the gas flares rise up over the sagebrush like portents of doom. I would be lying if I said I never thought about art.” I tend to be sceptical of this gothic treatment of working-class reality, in which being broke and doing unskilled jobs becomes a descent into the underworld and a purifying ordeal. But I have to admit it works here, if only because Kunzru does it so well.

When Kunzru returns to Jay and Alice in the present day, the book is less successful. It becomes a relatively familiar social satire of privileged people, who are unsurprisingly revealed as self-centred, weak-minded and spiritually empty. Rob, once a brilliant firebrand, now spends his days drinking and trying to sleep with his gallerist’s young girlfriend; Alice fumes about having to deal with the #MeToo accusations that gather in his wake. The gallerist, with whom they’re quarantining, has amassed an arsenal and fallen into fantasies of defending the house against a Covid-inspired breakdown in society.

No doubt there’s a point here about how the indulgence of the 90s led people to this decayed condition, in which all capacity for pleasure is exhausted, and no one feels strongly enough about anything even to drum up cynicism. But it gets a bit lost in long stretches of dialogue in which characters snipe at each other to demonstrate how shallow and unattractive they are. It’s also jarring to find Alice flattened into the two dimensions of satire, when we’ve previously known her as a complex, fully realised human being.

But as a whole, Blue Ruin is bracingly intelligent and often just plain beautiful. It’s a reminder that fiction, at its best, is a place to encounter new experiences and dwell in big ideas. Kunzru is known for ambitious novels that bring politics to rich, imaginative life; Blue Ruin shows him at the top of his game.

• Blue Ruin by Hari Kunzru is published by Scribner (£20). To support the Guardian and the Observer buy your copy from guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.