How 'Black Panther' Changed Stunt Work Forever

In the minds of most Marvel fans, there is only one Black Panther: the late Chadwick Boseman, who played King T’Challa in four Marvel films before dying in August 2020 after his battle with colon cancer. But underneath the suit, three stuntmen – Gui DaSilva-Greene, Daniel Graham and Anis Cheurfa – all doubled Boseman, working behind the scenes to give the character that superhero swagger. Whether he was sliding down a 100ft wall effortlessly, jumping from one moving car to another with feline dexterity or going punch for explosive punch and kick for percussive kick with Killmonger, Black Panther always moved with grace and power.

Coincidentally, DaSilva-Greene, Graham and Cheurfa began their ascent into Hollywood stunt pre-eminence while living together in a tiny apartment in north Hollywood, a decade before Black Panther premiered. Collectively, these three friends have performed stunts in six of the top 25 highest-grossing films of all time, including the four films in which they doubled Boseman: Captain America: Civil War, Avengers: Infinity War, Black Panther and Avengers: Endgame. It’s a body of work that not only changed their lives, but also signifies a turning point for the black stunt community, following decades of fighting to increase opportunities for people of colour in Hollywood. Through years of training, hustling, and at times luck, these men are now at the top of an industry that hasn’t always accepted performers who look like them.

Up until the mid-1960s, there were no black stunt performers in Hollywood. Instead of hiring black bodies to fill in for black actors, directors applied dark make-up to white actors – a technique known as ‘painting down’. Things started to change in 1965, when first-time actor Bill Cosby refused to have a white stuntman double him on the TV show I Spy, the first national television series to feature a black male actor in a lead role. Calvin Brown, a black actor and stuntman, doubled Cosby instead, launching his career as the first black stuntman recognised by Hollywood. After shattering his leg during a stunt a few years later, Brown founded the Black Stuntmen’s Association, an effort to pass on his skills and knowledge to other black performers looking to break into the industry.

Since then, the Black Stuntmen’s Association has filed dozens of anti-discrimination lawsuits seeking more inclusivity with regard to hiring in Hollywood. Although painting down and wigging – when a stuntman puts on a wig to double a woman – happen less frequently now, dozens of stunt performers still felt it necessary last year to petition their union to end the practices. The petition noted that employers and stunt coordinators still pass over qualified women and performers of colour ‘via nepotism, racism, intimidation and slander’, while ‘our talents are overlooked, denied and discredited, our professional opportunities foreclosed, our careers foreshortened’. It’s part of a history of anti-blackness within Hollywood, says actor and activist Kendrick Sampson, who spearheads BLD PWR, a non-profit working to dismantle racism in the entertainment industry. He adds that for stunt performers, ‘since they’re not as visible as actors, it’s hard to make progress’. Both seen and unseen, invisible to most eyes yet thrillingly, undeniably alive on screen, they’re helping to drive the long-overdue change in who gets to be a hero and kick some ass in Hollywood blockbusters. But breaking barriers was never really a goal for Cheurfa, DaSilva-Greene and Graham. They started out just wanting to kick each other’s asses.

The Real Hustle

The future roommates first crossed paths competing against one another at national martial arts tournaments, but they really bonded for the first time in 2008 at a ‘gathering’ at Loopkicks, a Santa Clara, California, gym specialising in tricking – a mash-up of martial arts, capoeira and gymnastics. A gathering is like a meet-up for martial artists where they can show off their tricking, similar to the way rappers and breakdancers congregate in a circle, during what’s known as a cypher. Instead of rhymes or dance moves, the battles at gatherings feature tricks, acrobatic flips, kicks and other gravity-defying martial-arts moves. Tricking became increasingly popular in the 1990s before ramping up even more during the early 2000s. Graham, DaSilva-Greene and Cheurfa are pioneers in the space, and tricking nourished their friendship and fuelled their careers.

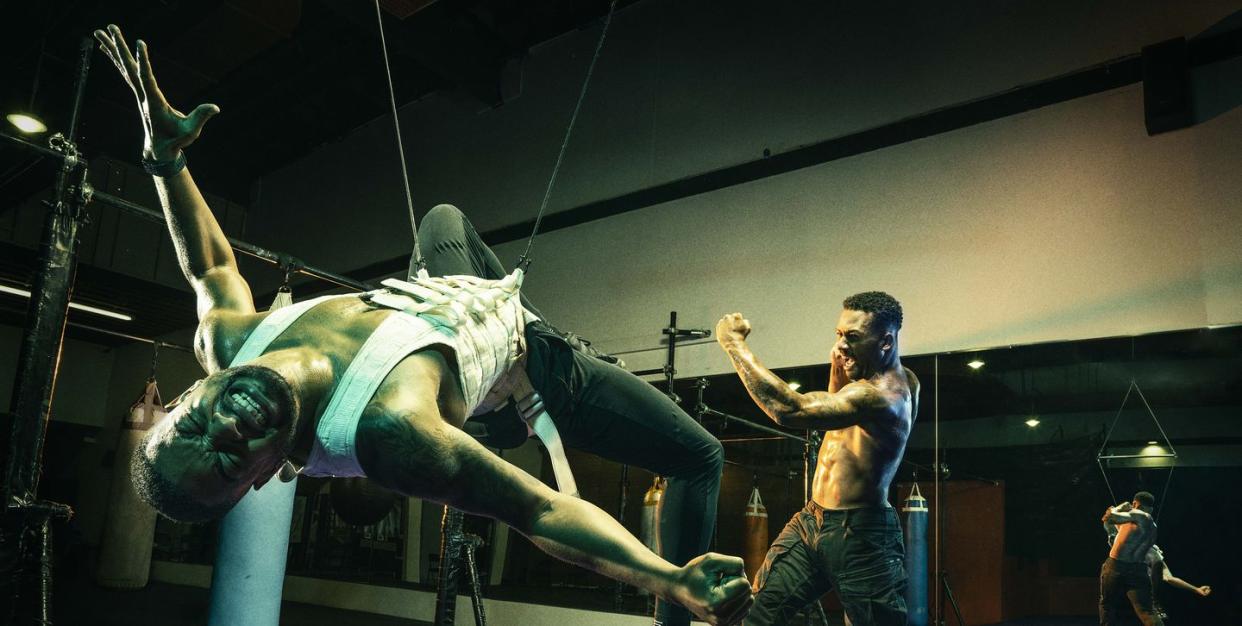

When MH meets up with Graham, 36, and DaSilva-Greene, 31, in August, both men are doing motion-capture work at a giant stunt gym called Joining All Movement in Reseda, California, for a movie franchise that has grossed several billion dollars worldwide but that they can’t name. Graham had drawn recent acclaim for his stunt work on Tenet, doubling John David Washington. ‘Danny’s the best, don’t get it twisted,’ says DaSilva-Greene as they embrace. (Cheurfa, 33, who is of French-Algerian descent and grew up

in Paris.) Graham and DaSilva-Greene seem as close as brothers, often finishing each other’s sentences and relishing their similarities and differences with laughter. Both are just about six feet tall with ripped physiques and around nine percentage points of total body fat between them. That’s where the similarities end. Graham is a softly spoken, meat-eating, Tesla-driving family man. DaSilva-Greene is a boisterous, vegan, single guy who roared up on a BMW S 1000 RR, a superbike. Over lunch – lobster burger for Graham, red-bean torta for DaSilva-Greene – the two poke fun at each other as they reminisce about the grind of their early days.

‘Every month was a new move,’ says Graham. ‘Somebody invented flares [in which you balance yourself on alternating hands as you continuously swing your legs beneath you]. And then somebody did air flares. And then one-handed air flares. Everything just evolved so quickly,’ he says, describing the scene in the 2000s. ‘Tricking used to be our life,’ says Cheurfa later, via Zoom.

‘We all would trick and train every day. It was crazy, bro,’ DaSilva-Greene says. After they all connected at Loopkicks, DaSilva-Greene moved in with Graham and Cheurfa to a two-bedroom apartment in 2009. Their rent came out to about $300 per month each. ‘We were sharing a room,’ DaSilva-Greene recalls. ‘You know, it was like, “Y’all three are in this room, and y’all two are in that room”’ – two other aspiring actors shared the other room. Most nights, they went to a martial-arts gym called White Lotus, run by Aaron Toney (who later co-founded Joining All Movement and was also a stuntman in Black Panther). ‘Everybody was trying to one-up each other, constantly pushing each other to be better in the gym and playing video games,’ adds Graham. ‘You want to be around people who lift you up, even when you’re flat broke, eating ramen or 80-cent tacos.’

The guys have interesting origin stories. Graham had been running a karate school in Florida but moved to Los Angeles to pursue his childhood dream of being a stuntman. ‘I remember when I was little watching The Last Dragon and seeing Bruce Leroy [played by Taimak Guarriello]. It was the first time I’d seen someone who looked like me doing martial arts, and it was like, “Oh, I could do this!”’ By age 10, he was competing nationally. He earned a black belt in taekwondo at 12 and eventually became a karate instructor. DaSilva-Greene grew up as a comic-book nerd in Harlem and aspired to be the first black Bruce Lee or Jackie Chan, martial-arts action stars famous for doing their own stunts. He trained in martial arts and worked as a back-up dancer for Chris Brown. ‘I had no family on the West Coast. It was just like, “Yo, you come out, you got to do something, you got to make it happen,”’ he says. Cheurfa’s background was also in martial arts and tricking. He’s a black belt in taekwondo and earned YouTube fame by performing 18 corkscrews – in which you jump on one leg, spin your body at an angle, then land on one leg – in a minute.

Cheurfa scored success first, playing Rinzler in 2010’s Tron: Legacy, a role involving lots of tricking moves. Graham and DaSilva-Greene picked up dance and stunt work in music videos and on television shows like NCIS. Then Cheurfa and Graham were hired by 87Eleven, the action-design team behind the John Wick series. Founded by Chad Stahelski – the stunt performer who doubled Keanu Reeves in The Matrix and went on to direct the John Wick films – 87Eleven is known for its level of accuracy and authenticity in choreographing fight sequences. Both men say the training was intense, eight-hour days rehearsing elaborate sequences again and again. ‘Everything is real fighting techniques,’ says Cheurfa. ‘We had to train for months and months at a time to look like we knew what we’re doing.’ DaSilva-Greene wasn’t invited to be part of that team because, as he says, ‘I wasn’t anywhere near the calibre of those guys then. Nor did I have a connection to get pulled in. So it was like, “Okay, you guys are doing that. I got to fend for myself.”’

While Graham and Cheurfa established themselves as bona fide stunt performers, working all over the world on films like The Hunger Games, Divergent and the Fast & Furious series, DaSilva-Greene continued to hone his skills. ‘I was lucky to maybe double a small-time actor, or I was like goon number five or police officer number three, you know? It was like very small things,’ he says. ‘I come in, I throw a right punch, I get hit and I hit the ground. That was my job.’ Like some of his role models, DaSilva-Greene dipped his hand into the indie-film world to build up a portfolio. ‘There’s always been like an indie martial-art film world, like the Shaw Brothers films, Jackie Chan movies, Van Damme’s early work. And with that comes imitation,’ he says. YouTube has allowed creators like him to put together tricking and stunt highlight reels, called samplers, and reach hundreds of thousands of viewers while also landing on the radar of people in the industry. ‘Some of those videos got noticed. And a lot of people in the stunt community, especially stunt coordinators, the guys who do the hiring, they’re watching, they’re looking to see what’s new, who’s out there, who can they pull in.’ That’s how DaSilva-Greene garnered the attention of Tom Harper, a stunt coordinator for Captain America: The Winter Soldier, and found himself getting beaten up in a lift.

Pulling Stunts

It’s one of the most iconic action sequences of Winter Soldier, the Marvel epic filmed in 2013. Cap is in a lift surrounded by nine rogue agents who want to capture him, and he asks, ‘Before we get started, does anyone want to get out?’ Gui DaSilva-Greene knew he wanted in: it was a minor stunt, but a chance to prove he belonged. ‘It was only supposed to be like, I think, two weeks of work,’ he says. ‘You see my dumb ass walk in, in the beginning behind Frank Grillo. We practised 10 days to shoot that three-minute fight scene.’ When the brawl broke out, DaSilva-Greene had to do a challenging manoeuvre that involved getting kicked by Cap, launching horizontally in the air, spinning, and then hitting the glass lift wall before landing on the floor. ‘I don’t have much space, and there’s a bar that’s, like, at three-feet high,’ he says. ‘So I have to clear the bar and then get down on the floor.’ As one of the youngest and least experienced people on set, DaSilva-Greene felt the stress. ‘Everybody’s in their early thirties. They’ve been in the game for a while, and so they treated me like the little scrub, which I was.’

As a black performer in a white-male-dominated industry, DaSilva-Greene says there’s an existential pressure to be great at all times, but also not too great, to the point that you threaten other people’s confidence, a tricky, inequitable predicament that people of colour in all industries are forced to reckon with. And there are very few second chances. ‘You get one shot. If you fuck up, that’s just the end of you,’ he says bluntly. He performed the move in Winter Soldier flawlessly, earning him the respect of his peers. ‘They’re like, “Okay, new guy’s talented. That’s how he got the job.”’ Despite his character getting knocked out early in the fight, DaSilva-Greene’s performance in the lift led to Harper offering him a couple more weeks on the shoot. There was a catch, though. Harper asked if he was afraid of heights. ‘I’m like, “No, whatever. I’ve been on roller coasters before,”’ DaSilva-Greene says. Whether he felt comfortable or not, he knew that he had to take chances to get to the next level.

What he didn’t realise at the time was that he’d be rappelling roughly 100 feet off a ship down to a concrete pier at night, 12 hours a day for another two weeks, just to rehearse the scene. ‘I can show you one of my first clips of me jumping off that thing. I am stiff as

a board,’ says DaSilva-Greene, laughing. ‘It’s a completely different type of fear from being afraid of heights. It’s like, “Do you trust the rigging system that you’re about to be using?” And that’s what some people will consider makes you a great stuntman, trusting the coordinator.’ After watching one of his initial attempts, Harper wasn’t impressed. ‘He sees me and he’s like, “Yo, who is that up there?” And they’re like, “Oh, that’s our new kid.” The stunt coordinator’s like, “Tell him he sucks.”’

With practise, DaSilva-Greene got the hang of descending from the ship. Making an impression while being put in uncomfortable situations, he caught the attention of Phil Cervera, another stunt coordinator on the film, who offered to help him out. ‘Phil liked my energy. He’s from New York, so we kind of vibed.’ Opportunities snowballed from there. ‘You meet more and more people, get more and more opportunities.’ DaSilva-Greene worked on Guardians Of The Galaxy and Deadpool, as well as on smaller productions. Then, in 2014, he put doubling Boseman in Captain America: Civil War on his wall as a goal.

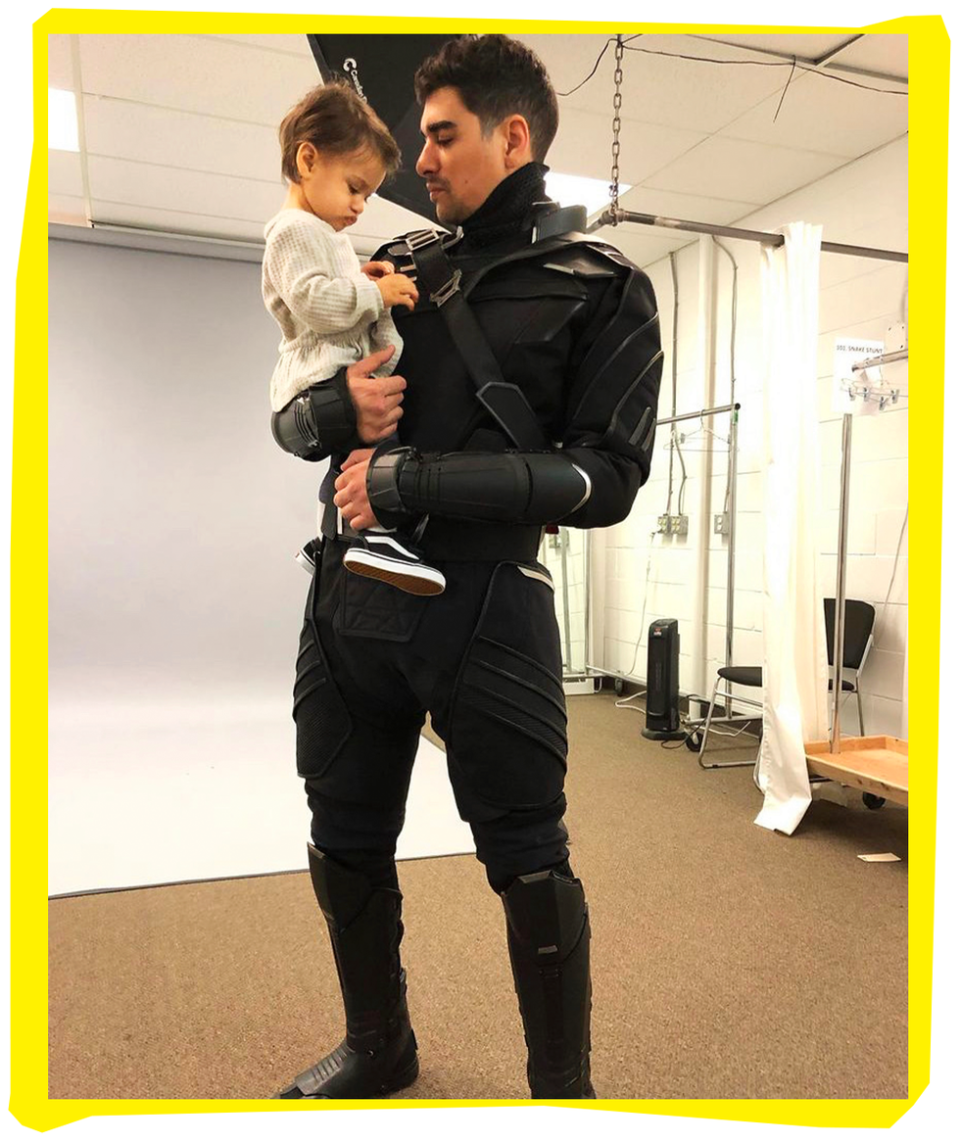

Most stunt jobs don’t require auditions – usually stunt coordinators hire by word of mouth – but for this role DaSilva-Greene got called in to audition and perform choreographed moves at 87Eleven. He knew the stunt coordinators doing the hiring and felt confident. ‘I’d worked to be in this position and knew I had to do what I do. Everybody can flip off one leg and spin, and so it’s more about how you perform it. I tried to make every move look as panther-y as possible.’ He adds that he once auditioned for Madonna, ‘all-day dance choreography, non-stop. This wasn’t that.’ Then he waited a year.

‘I finally get a phone call from Sam Hargrave’ – the stunt coordinator for Civil War. ‘He’s like, “Hey, buddy. I would like to invite you to be a part of Captain America: Civil War’s stunt team as Black Panther’s stunt double.”’ Working as a stunt double for a major character is a step up from doing utility stunts. He was in a car when he got the call. ‘I got out and was screaming. It was probably one of the biggest things that ever happened, you know, especially for a black kid from Harlem who’s read the comics.’ The following month, he was on set. ‘Now I’ve reached the pinnacle: black superhero. I got to be the

first time you see this black superhero on film.’

‘When I found out Gui was Black Panther in Civil War, I was happy for him,’ says Graham, who was busy doubling Raphael in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and O’Shea Jackson Jr, as Ice Cube, in Straight Outta Compton. ‘We all are happy for each other, because there is work everywhere.’ DaSilva-Greene describes working on Civil War as epic. ‘I got to do a lot of things I thought I’d never do. Survived a lot of things I thought I’d never survive. And of course, they made me jump off shit all the time,’ he says. He’s especially proud of the scene in which he leaps off the back of one car on to the back of another.

Meanwhile, Graham’s reputation had gone from strength to strength. He was tapped to double Boseman in the Black Panther movie, directed by Ryan Coogler. That news hit DaSilva-Greene, after doubling Boseman in Civil War, hard. ‘I’m like, damn, that kind of sucks,’ he says. ‘But at the same time, I’m like, “Yo, that’s one of my closest friends. We went through the grind of coming out here and trying to make it work.” So fuck yeah. Like, why not share it?’

It was a huge moment for Graham. ‘Black Panther represented the first black superhero movie; it’s, like, so big in our community. To be a part of that, I think that’s cool,’ he says. Because Marvel shot the Black Panther movie at the same time as the Avengers films, the directors needed another stuntman, which led to Cheurfa being recruited. ‘So all three of us got to play Black Panther... pretty amazing,’ Cheurfa says. All three of the performers say the films changed their lives and created a monumental shift in the stunt world.

Screen Time

‘Black Panther was very important both in front of and behind the camera,’ says Eric Sigmon, an editor of Black Action Stars, a website that covers black stunt performers and other minorities in the industry. ‘Basically every major department, a black person was either heavily involved or they led the entire department.’ Sigmon adds that playing Black Panther required DaSilva-Greene, Graham and Cheurfa to show proficiency in a wide range of skills. ‘They can do physical stunts, falling, getting hit. But they also do the fighting stunts and the wirework and all this. So yes, definitely a turning point.’ Prior to Black Panther, there were only a handful of black stunt performers considered to be at the top of their field. Now DaSilva-Greene and Graham say there are dozens. The Black Panther movie in particular created many chances for new talent – more than 200 stunt performers worked on it, including Toney and several other stuntmen who doubled Boseman in and out of the suit. ‘There’s all these dudes that were given opportunities and given the shot because they had to be given a shot,’ DaSilva-Greene says. ‘Before, it used to be like, “Well, we don’t need the black guy.”’

As dismal the pandemic was for movie business, it also marked a milestone as far as representation in Hollywood goes. For women and people of colour, 2020 was the first year that they reached ‘proportionate representation among film leads’, meaning that their share of lead film roles was representative of their general population share, according to a study from the University of California, Los Angeles. Among cast members overall, 2020 was the first year that minorities exceeded proportionate representation, according to the same study. Nearly one in five of all film roles went to black actors two years ago. Still, actors and stunt performers are pushing for more than just equal representation. ‘I’ve personally witnessed, you know, trying to paint up white actors for stunts, right?’ says Sampson, the actor and activist. ‘Where I’m like, I know there are black people available. The stunts aren’t dangerous... It takes people like actors and people in higher positions of privilege or more visible positions of privilege to join in solidarity and speak out against those things publicly so they can change, and it takes significant investment by producers, studios. Making sure we have black stunt coordinators and making sure they’re invested in our liberation, not just diversity and inclusion.’

After Boseman died, Marvel announced that it would not be recasting the role of T’Challa in Black Panther 2, and Cheurfa agrees with the call. ‘I think that’s the way it should have been,’ he says. But not all the former roommates feel that way. The decision not to recast T’Challa didn’t sit well with DaSilva-Greene. ‘These characters are meant to last forever, and they do because we as fans see ourselves in them, and to close the door on someone so iconic hurts just as much as losing Chadwick,’ he says. Plus, he notes, Superman and Batman have been recast over and over. Remember all the Batmen? Michael Keaton, Val Kilmer, George Clooney, Christian Bale, Ben Affleck, Robert Pattinson. It’s a tough one, adds Sampson. ‘I think what is here is an opportunity to allow black creatives to create a character just as iconic, or lift up a character that is already in that universe of Black Panther that will be iconic.’

Marvel knows how to keep a secret, but there are already rumours (based on existing Black Panther storylines) that the third film might involve a new Black Panther, and so the character may live on. DaSilva-Greene, Graham, and Cheurfa aren’t holding their breath, though. That’s not how the stunt world works. Instead, it’s the type of job that always calls for having a bag ready to go. One week, they might be doing prep work in a giant gym in Reseda, California. The following week, they might get called to be the next black superhero. This is the life they dreamed of living.

You Might Also Like