From billions to broke: The countess who is auctioning off her life

Everything must go. From the ruby red antique ikat cushions to the Regency japanned cabinet, and even her children’s doll’s house, the contents of Countess Alexandra Tolstoy’s haute bohemian home in Chelsea are to be sold at auction at Christie’s next month. She flashes a smile. ‘I thought I’d be devastated, but I’m not,’ she says. ‘I’m excited to be passing these things on to someone else who will love them.’ Does she ever feel a wobble? ‘Only in the middle of the night. Then I feel very shaky.’

As the partner of the oligarch Sergei Pugachev, she was, for a time, super-rich. ‘I’m glad I experienced that crazy world,’ she says. A BBC documentary, The Countess and the Russian Billionaire, which aired in April, revealed their lavish former lifestyle. They had three yachts, worth a total of $65 million, two private jets and a beachfront house in St Barts, as well as a mansion in Russia, a chateau in France and a beautiful family home in Chelsea.

But his status and empire began to crumble after the collapse of his Russian private bank – he was accused of siphoning off money from its bailout, an allegation he has denied. In 2014 his assets were frozen by a London court, part of a dispute with Russia’s state deposit agency. The couple’s relationship imploded on camera for the documentary, which was filmed over five years.

A key moment was when Pugachev failed to turn up at Tolstoy’s father’s 80th birthday. He had disappeared and surfaced in his well-defended Côte D’Azur chateau. Tolstoy says he hadn’t even told her he was going.

‘I felt the documentary glamorised him too much,’ she tells me. ‘It made him into a Scarlet Pimpernel. I think they were quite seduced by him and in awe of him as he’s so rich and powerful. Yes, he clearly did fall out with Putin, and I still don’t know why. But he’s not a political martyr…’ She adds: ‘Sergei running off was the best thing that happened to us.’

She claims that he cut her off when she refused to stay with him in France, where he still lives in exile. She returned to their multimillion-pound Chelsea house and remained there with their children, Aliosha, now 11, Ivan, 10, and Maria, eight, until they were evicted this summer by Pugachev’s Russian creditors. The jasmine is now growing over the windows as it sits unoccupied.

‘He hasn’t given us a penny since 2016. And I don’t ask him for anything,’ she says matter-of-factly. ‘I don’t want to be under his control… I’ve come to terms with it now and I’m so happy to let go of these things.’ She is selling her furniture and objets d’art in order to fund her future, and walking away with her freedom, her kitchen table and her rocking horse.

Is the rocking horse really essential? ‘Well my children do still ride him!’

Tolstoy is very likeable, though she comes from a different planet to the rest of us. She is 47 and has lived her life like a character in a novel, sometimes like one by her distant relative Leo Tolstoy, sometimes more Jilly Cooper. When I meet her in south London, near her new home, she is cheerful and looking fresh as a daisy in a folk blouse and a raspberry cardigan. She has a plummy English accent, a title (though she never uses it) and a peaches-and-cream beauty.

As a girl she had a burning desire to escape her upper-middle-class Oxfordshire upbringing. At 30 she married a penniless Uzbek horseman, Shamil Galimzyanov, set up home with him in Moscow and spent a large chunk of her inheritance buying him showjumpers. ‘They were ruinous,’ she sighs. ‘More expensive than children!’

To keep herself, Galimzyanov and their horses afloat she took on jobs including teaching English conversation to oligarchs, which was how, in 2006, she met Pugachev. He was then a Russian senator, known as ‘Putin’s banker’ and one of the President’s inner circle, worth at least $1.3 billion (or $15 billion at his own estimation), with properties in Red Square, shipyards and a bank.

They didn’t get together until two years later, when her marriage had broken down and they met again at a charity ball in St Petersburg. Tolstoy says she felt frumpy next to supermodel Natalia Vodianova, who was also at their table, but riveted by Pugachev’s powerful demeanour she spoke with him in Russian all night about Soviet history, books, family, everything. ‘There was just the most intense attraction.’

Soon she was being ferried around the world on private jets and choosing cabinets for Pugachev’s favourite yacht. Within a year, she was pregnant. ‘I was living at Claridge’s,’ she says, with a twinkle at the absurdity of it, ‘and I realised we needed a London base. I didn’t want to give birth in Moscow.’

They rented an artist’s studio in Glebe Place, and liked it so much that they bought it, along with the one next door, knocking them together to make a six-bedroom, five-bathroom house. ‘It was playful and cosy,’ says Tolstoy. ‘Not pompous or grand like a big up-and-down house in Belgrave Square.’

She decorated it with the help of England’s longest established interior decorating firm, Sibyl Colefax & John Fowler, in traditional country house style mixed with Slavic treasures from her travels. Next month 130 pieces will be sold at Christie’s London, among them antique bookcases, armchairs, linen cupboards, precious artworks that once hung in the children’s bedroom, and a chalkboard that they used to play with designed by Linley, the furniture maker founded by Princess Margaret’s son David Linley.

A standout lot is a 19th-century pine model of St Sergius monastery outside Moscow, set on a mirror on a slate table (estimate £2,000-£3,000). ‘It does make me sad to part with that,’ Tolstoy says. ‘I visited there in the early 1990s when I went on my own to Russia for the first time, just as it was opening up to the West, when I fell in love with the language and Russia itself.’

Pugachev turned out to be, shall we say, unreliable. They never married, though he repeatedly promised her father that they would. ‘Had we married, it would have been a lot easier to get maintenance. But as it is, I have no rights at all,’ she says. ‘I could go to France and take him to court but it would be so negative – I’d rather get on with my own life and my own projects.’

She seems much happier now than last year, when I first interviewed her for this magazine. We sat at Glebe Place among burning candles, icons and exquisite objets as she told me her priest had advised her to leave Pugachev for the sake of their children. She was also aware that Pugachev’s creditors might claim her house at any moment, and she was tense, like a canary in a gilded cage.

‘It was a wonderful home but it was also a place where I had been frightened and at the mercy of his many moods,’ she tells me. (He rejects her description of their relationship entirely.)

It was where they had ‘so much fun’, too, Tolstoy continues. ‘Children’s parties, musical statues, hide and seek in laundry baskets and up ladders, hilarious dinner parties, where I’d cook all day… We made the most of that house, I must say.’

In May this year the axe finally fell and, at the height of the coronavirus pandemic, she received the long-dreaded letter: 'You will be required to vacate the property 53-54 Glebe Place.'

‘This was our home, where I brought our children back to from hospital,’ says Tolstoy. ‘It’s painful, of course. But I have to make the right choice for them long-term.’ She sent the children off to their aunt’s and got on with it. A decluttering guru helped her for free. ‘Moving to a much smaller place is a challenge and literally nothing fits – the one rug I’m keeping is going to have to be cut down to size for two rooms.’

She was comforted by the fact that the children didn’t seem too upset. ‘They’ve become very philosophical [about selling the furniture],’ she says. ‘I always ask them first before making a decision and we discuss it.’ They were more worried about keeping their Star Wars posters than the pair of rare felt and velvet collage pictures by British folk artist George Smart that had hung on their bedroom wall for 10 years – and are now set to go under the hammer (for an estimated £3,000-£5,000 for the two). Many of the other items to be auctioned were sourced from attic sales at Chatsworth, Denham Court and Spencer House.

She handed the keys to the estate agent, and moved back in with her parents in Oxfordshire for the remainder of lockdown. ‘We were so lucky, the children could do boating, tree climbing, absolute freedom.’ Her father read aloud from The Hobbit and the children sometimes slept outside in her showman’s wagon, an exquisite little painted caravan of the type beloved by Mr Toad, with an interior including tiles and a real stove. ‘It needs more maintenance than we can afford to give it,’ she says. ‘So that will be in the Christie’s sale too. The children were understanding. Instead we built them a Baba Yaga tree house in the poplars.’

The Tolstoys have a romantic approach to life, perhaps born of their many reversals of fortune. Alexandra’s paternal family lost their estates in the Russian revolution. Her father, Count Tolstoy, an author and historian, continued the tradition of jeopardy. In 1989, he was ordered to pay libel damages of £1.5 million to Lord Aldington, whom he had accused of war crimes, a landmark sum at the time.

Time with her parents during lockdown was ‘wonderful, of course, but as an adult you want to be self-governing’. The new place, a rented Victorian terraced house south of the river, allows her to keep her children at their school. They have their own rooms for the first time. ‘They always shared a bedroom. So much more fun for them, so many shared jokes. And I could read to all of them tucked up in their beds.’

Fairy tales have helped save their sanity, she tells me. ‘It was the same for my father, who grew up in the middle of the most appalling divorce and lived in the world of Ivanhoe.’ That romance by Sir Walter Scott was a refuge for him as he was prevented from seeing his mother after she left his father, Count Dimitri Tolstoy QC, for the writer Patrick O’Brian, author of the Aubrey-Maturin novels, including Master and Commander. But her father’s disrupted childhood brought an unexpected financial legacy. The proceeds from those novels was shared between O’Brian’s step-grandchildren, so Alexandra still receives an annual payment. ‘We’re very lucky,’ she says.

Her share of the inheritance from his estate also allowed her to buy a small cottage in Oxfordshire, which she decorated in a stylishly traditional manner. It is now her main source of income, rented out as a holiday home. ‘The cottage has been the best investment because of Covid,’ she tells me. ‘It’s in real demand and pays our rent in London.’

The pandemic forced her to mothball her adventure-travel company based in Kyrgyzstan, so she has set up an online clothes and furniture boutique, The Tolstoy Edit. She resells friends’ clothes, spots interiors gems and is collaborating with designers. ‘Last month we turned over £20,000,’ she says, sounding a little surprised. The Christie’s sale – which should have a global reach, enhanced by Tolstoy’s 62.8k Instagram following – will allow her to invest in the project long-term.

Her vision of what a home should be was moulded by growing up in her parents’ farmhouse. It was, she says, ‘full of antiques, faded textiles and rugs, all with that air of scruffiness so essential to an English country house’. Meanwhile Glebe Place was a beautiful creation, layered and warm. ‘Everything I bought I tried to make original and unusual in its own right,’ she says.

‘Obviously it’s heartbreaking to be moving on from a home you love,’ says Benedict Winter, head of sale at Christie’s, ‘but Alexandra has a real passion for interiors… She’s a doyenne of style. Her travels and her personal, rather quirky taste are very much in evidence here.’ Winter picks as his personal favourite lot the coveted John Fowler waste-paper bin: ‘So chic!’ When I look it up, I see the estimate is £300-£500 (albeit for three).

‘I don’t miss any of that excess, that crazy, super-charged lifestyle,’ says Tolstoy. She spoke to a therapist who told her that people who remain hopeful of regaining their former status are the ones who struggle to be happy. She is thrilled to be setting up a new home, where her new furniture will be painted with folk-inspired stencils and the walls are a strong ochre. ‘I feel more focused here. A smaller house is just simpler to live in. I think of Sergei in France surrounded by hundreds of the silver art deco decanters he collects… It bogs you down, all that stuff.’

She used to have a private chef who would make them fresh blinis, sushi, anything they wanted for breakfast; now her Instagram feed shows cornflakes. There are some things she misses. ‘Of course I would love to be able to afford to take my children skiing,’ she says. She recently sold a diamond necklace, a Cartier Rivière, so she could buy a second-hand Aga. But she adds: ‘It’s a release, in a way. Owning jewellery like that is stressful, it’s a liability. I don’t want to wear it and it’s the only thing I had left.’ Apart from her taste and her style, which, of course, can never be lost – although it can be sold.

‘I’m glad I lived that life,’ she says. ‘I learned that if you’re unhappy you’re unhappy, your emotions are the same whatever your financial circumstances. It’s very tempting to be judgmental of rich people. Lots of people are. The assumption is that a rich person is a bad mother, not engaged, absent, frivolous… These are really bad, unfair assumptions.’

Well, someone had to speak up for those poor misjudged oligarchs. Millions wouldn’t. Perhaps it could only be somebody who has had it all and moved beyond it.

Christie’s London, A Private & Iconic Collections auction. Alexandra Tolstoy: A Sibyl Colefax & John Fowler Interior. Online 4 November for bidding and browsing, until 25 November (christies.com)

Follow Alexandra on Instagram: @alexandratolstoy

A HOME FOR SALE

Alexandra Tolstoy’s most treasured pieces to be auctioned at Christie’s London next month

English Mahogany wing armchair

19th century and later; £1,200-£1,800

‘A good armchair is so key and this one is particularly comfortable and sweet.’

Anglo-Dutch black and gilt Japanned linen cupboard

Early 18th century £2,000-£3,000

‘Against a white wall, japanned furniture always looks sumptuous.’

Hermes Balcon Du Guadalquivir Porcelain service

20th century £2,000-£4,000

‘These are new but have a vintage look. I love the strong red and white swirls, which look almost Uzbek. I had so many dinner parties but somehow didn’t break anything.’

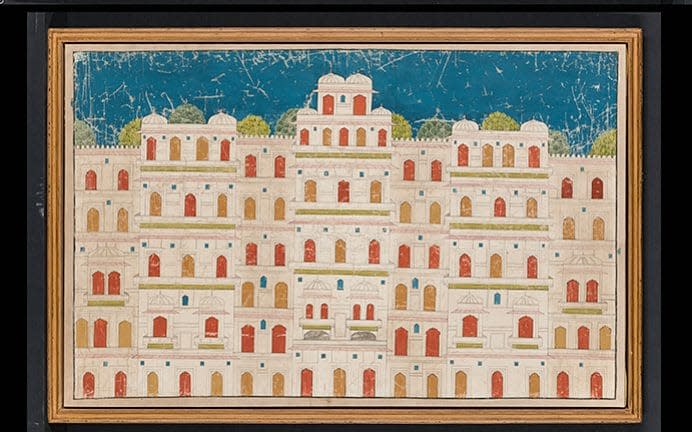

Pair of Indian Architectural paintings (one shown)

20th century £1,000-£2,000

‘These were chosen for their huge scale and stunning colours.’