Beyond the Wall by Katja Hoyer review – the human face of the socialist state

East Germany is one of Europe’s ghosts. Katja Hoyer is just old enough to remember its demise. In October 1989, when she was four years old, her father took her on a trip to the top of Berlin’s Fernsehturm, or Television Tower. Then, and now, the tallest building in Germany, this “masterpiece of socialist architecture” was built between 1965 and 1969 as a demonstration of East Germany’s technological prowess. But on that day in October, when Hoyer looked down, she saw squads of the “People’s Police” arresting protesters on the massive cement square below. Neither policemen nor the protesters could have known that in a mere month, the Berlin Wall would fall. Nor would they have imagined that in a year’s time, the German Democratic Republic (or GDR) would cease to exist.

Thirty years after its passing, Hoyer, now a journalist and historian, has returned to the land of her birth, with this rich, counterintuitive history of a country all too often dismissed as a freak or accident of the cold war. Hoyer’s East Germany is not, though, the walled-in, Russian-controlled “Stasiland”, whose citizens suffered from constant surveillance and intimidation at the hands of the Ministry for State Security. Rather, in her telling, it was a place where people shaped their own destinies and lived lives in “full colour” – a far cry from the “grey, monotonous blur” conjured by the western imagination.

Unemployment barely existed. Housing was universally available and relatively cheap

Hoyer’s East Germany was also a state whose leaders, although propped up by the Red Army, and dependent on the Soviet Union for critical raw materials (in particular, oil), sought to navigate an independent path at home and on the international stage. Her account is largely a political history, although one interspersed with interviews with ordinary East Germans, “teachers, accountants… factory workers” and, more tellingly, the “police officers and border guards” who made the state work.

Originally under Soviet army occupation following the end of the second world war, East Germany became an independent country on 7 October 1949. But the story Hoyer tells in Beyond the Wall starts much earlier with the German Communist party’s struggle to survive “between Hitler and Stalin”. In the run-up to the second world war, party members faced arrest and torture in Nazi Germany. This drove much of its leadership into exile in the Soviet Union, where most eventually perished, either in the gulags or by firing squad, as victims of Stalin’s purges.

The remnant of the party that survived to take over East Germany after the war was battle-hardened and utterly loyal to its Soviet masters. Brought to Germany by the invading Red Army, the party’s leaders – most notably Walter Ulbricht and Wilhelm Pieck – began establishing a communist-led dictatorship in the Soviet occupied zone. In a few years, they succeeded in rapidly transforming the social, economic and political organisation of the east by redistributing land, nationalising industry and quashing any organised political opposition. In the process, they triggered a mass exodus across the still open border to the west.

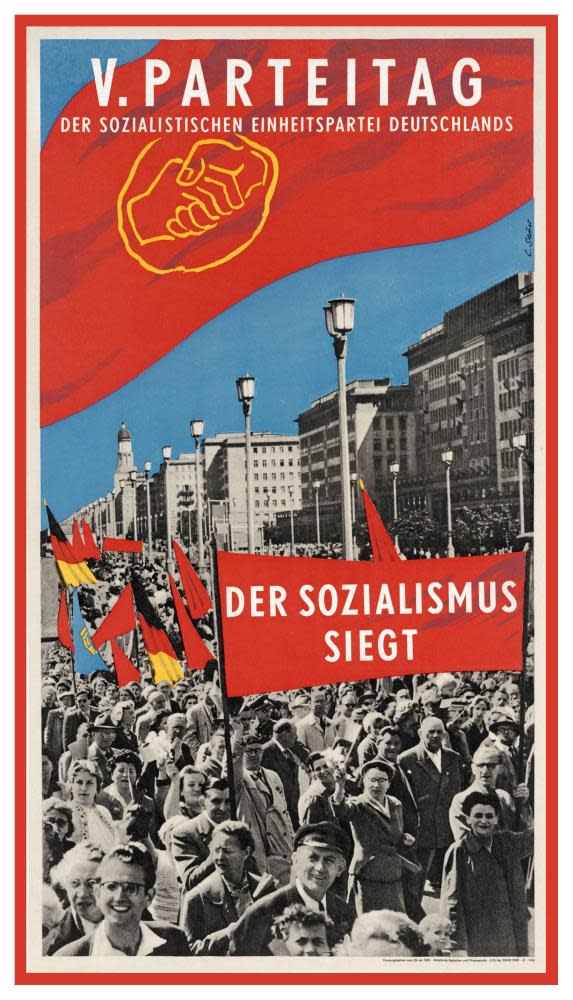

Following Stalin’s death in 1953, the Communist party (restyled as the more inclusive-sounding Socialist Unity party, or SED) ruled East Germany with a mixture of repression and accommodation. On one hand, the role of state security – the dreaded Stasi – expanded enormously. On the other, the party leadership did what it could to ensure that all East Germans were at least gainfully employed and had their basic needs met. But it was not enough; as long as an escape route remained open in the divided city of Berlin, East Germany continued to haemorrhage skilled workers to the west. By 1961, almost 300,000 people were leaving the GDR every year. That year, the GDR’s party head and unquestioned leader, Ulbricht, decided to put a stop to this flight once and for all by building the Berlin Wall – something he achieved (at least in its initial, wood-and-barbed wire phase) practically overnight and against the objections of his Soviet minders.

Trapped behind barbed wire, but increasingly prosperous, East Germany began to resemble the gilded cage of the eastern bloc, at least in the eyes of its socialist neighbours. However, as Hoyer points out, at least the gilding was real: East Germany really did enjoy the highest standard of living of any socialist state. Unemployment barely existed. Housing was universally available and relatively cheap. Abundant, accessible childcare allowed women to enter the workforce at a higher rate than in any other country in the world. As Erika Krüger, one of the workers Hoyer interviewed, recalled, life in the 1970s and 80s was “quite happy”: “We worked, received our regular wages as well as bonuses for hard work. We got by and had nothing to worry about.”

It was only when Krüger visited her sister-in-law in West Germany that she realised the gap in living standards between east and west. But if East Germany lagged behind in the production of consumer goods, and especially luxuries, one of the many surprises of Beyond the Wall is the revelation of the extreme lengths the East German leadership was willing to go to keep its populace supplied with the imported goods and foodstuffs it considered essential to their emotional wellbeing.

People were provided with stability, relative prosperity and social mobility. It was a workers’ state that catered to workers’ interests. All of which prompts the question – why did it also build the largest per capita security system the world has ever known? Hoyer places most of the blame on “paranoia”, especially on the part of the Stasi’s shadowy boss, Erich Mielke. But one man does not a system make.

It is here where one occasionally wishes that Hoyer broadened her vision from East Germany to the eastern bloc as a whole. A comparative viewpoint might have made clearer the peculiarity of East Germany’s achievement and its tragedy. Both were rooted in the same geographic fact. As part of a larger, pre-war Germany, East Germany was faced with the constant counter-example of the neighbouring Federal Republic. Its proximity just over the Wall encouraged its leadership to make their version of socialism as effective as humanly possible. It also pushed them to create one of the most extensive systems of control the world has ever seen.

Goodbye Eastern Europe by Jacob Mikanowski is published next month (Oneworld)

• Beyond the Wall: East Germany, 1949-1990 by Katja Hoyer is published by Allen Lane (£25). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply