Best graphic novels of 2023

Comics have always been interested in the strangeness that lurks beneath everyday life, and many of 2023’s best graphic novels dig into weird places. Why Don’t You Love Me? (Drawn & Quarterly) follows a couple struggling through parenthood and blagging their way in baffling jobs. British cartoonist Paul B Rainey builds his story from bleakly humorous page-long strips, while the larger question – how, exactly, did these absurdly underqualified people get to where they are? – slowly moves into focus, giving his inventive drama a real emotional weight.

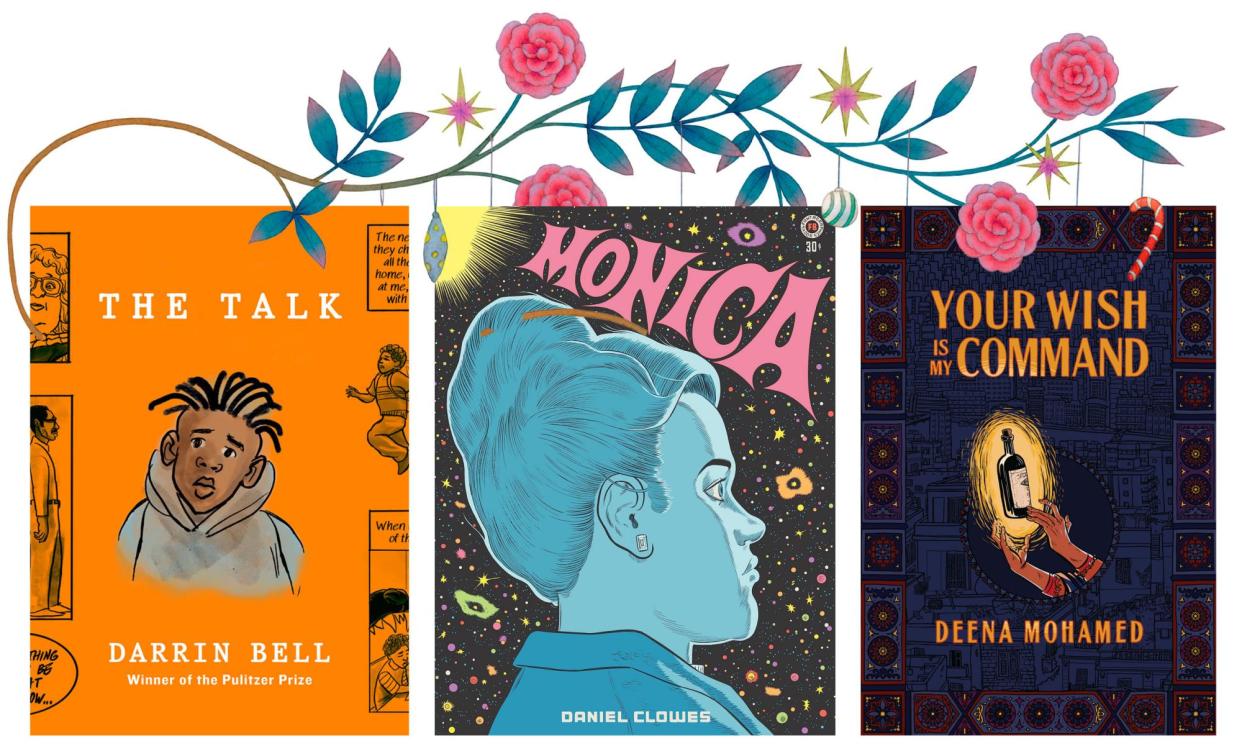

The year’s most eagerly awaited work, Daniel Clowes’s Monica (Cape), follows a woman’s search for her mother. The veteran cartoonist gives us strange cults, conspiracy theorists and episodes that skip from genre to genre, in a book that’s philosophical as well as playful, and one of his best.

Pulitzer winner Darrin Bell produced another American classic. His memoir The Talk (Cape) tells of suspicious cops and store assistants, playground bullies and smirking professors – all of whom singled out Bell because he is Black. Bell places these incidents of bias and thuggery alongside his family life and growing success as a comics artist in an expressive and direct work about racism’s impact, and the problems we have discussing it.

Thomas Girtin: The Forgotten Painter (SelfMadeHero) is Oscar Zarate’s best work yet. The Argentinian graphic novelist, who has lived in Britain for half a century, sets the tale of Girtin, the watercolour pioneer who was overshadowed by his contemporary JMW Turner, alongside an account of the increasing bond between three modern-day drawing-class buddies. It’s a heartfelt tribute to both friendship and Girtin’s art, which is reproduced in lovely fold-out spreads.

Two fine graphic novels explored horror this year. Sammy Harkham’s Blood of the Virgin (Pantheon) follows a Jewish American scriptwriter’s attempts to make a low-budget horror movie in 1970s Hollywood while helping to raise his young son. It’s a richly evocative account, from the inventive special effects, cheesy dialogue and frantic pace of shoestring film-making to the rosy glow of palm trees and boulevards in the post-party dawn.

Emily Carroll’s A Guest in the House (Faber), meanwhile, tells of a young newlywed who is visited by the ghost of her husband’s former wife, but starts to wonder if her taciturn partner is the bigger threat. Imagination and the supernatural bring bursts of febrile colour into the mostly black-and-white pages of an atmospheric and unsettling book.

Supernatural forces also loom large in Deena Mohamed’s Your Wish Is My Command (Granta), which imagines a world where wishes are real. Three Cairo residents – a persecuted widow, a conflicted student and a pensive stall owner – agonise over what to do with theirs in an imaginative, thoughtful and dynamically drawn debut.

There’s drama aplenty in Roaming by Jillian Tamaki and Mariko Tamaki (Drawn & Quarterly), which follows three Canadian students on a trip to New York City. They encounter grumpy gallery workers and Times Square hustlers, scoff pizza, try on clothes and bicker. It’s a fizzing, brilliantly observed tale of the kind of youthful city break that might only last days but can echo for a lifetime.

Roaming is set in 2009, with social media not yet quite everywhere, but French manga fan Léa Murawiec’s The Great Beyond (Drawn & Quarterly; translated by Aleshia Jensen) tells of a near future where “presence” is essential for survival. Lack of social exposure leaves Manel close to death until she’s involved in a fracas that goes viral. This fun satire is distinguished by its wonderfully fluid artwork: a startling geometry of soaring tower blocks, teeming streets and outstretched limbs.

The power of comics to surprise remains undimmed. Begun more than 30 years ago, Anke Feuchtenberger and Katrin de Vries’s W the Whore (New York Review Comics) has been collected in its entirety in English (translated from the German by Mark David Nevins) for the first time. Its heroine negotiates desire, marriage and childbirth in a stark, intimate and sometimes very funny book about life and gender roles. What Awaits Them (Breakdown) brings British artist Liam Cobb’s short comics together in a violent, vivid collection. Strange fruit are eaten, buildings are reborn and a grudge over a horse escalates as Cobb’s characters teeter on the edge of madness or destruction.

Two very different epic histories were published this year. Okinawa (Fantagraphics) collects Susumu Higa’s manga Sword of Sand (1995) and Mabui (2010) in a translation by Jocelyne Allen. It begins as a Japanese garrison arrives on an Okinawan island in the 1940s and ends some 50 years later, with US military bases still a dominant presence. Higa brings this vast sweep to life with affecting, instantly approachable episodes that touch on war, faith, local politics and stolen antiquities, shining a light on an often marginalised region.

Ed Piskor has been making comics about the early years of hip-hop for a decade. His Hip Hop Family Tree: The Omnibus (Fantagraphics) connects all four volumes in a biblical opus that features Kurtis Blow, Grandmaster Flash and Beastie Boys. But rather than the big names, it’s the small touches – bit-part players, intriguing asides and a vintage palette – that really bring classic rap to life. On the 50th anniversary of a genre that rose from the back streets of the Bronx to rule the world, it’s hard to think of a better present for a hip-hop head.Alt-rock fans might prefer Leslie Stein’s Brooklyn’s Last Secret (Drawn & Quarterly), a sharp-eyed, addictively affectionate account of a never-quite-made-it indie band who, propelled by hummus, weed lollipops and chugging guitar riffs, embark on one last tour and gain something like closure. Until the 2043 reformation tour, of course.

• To browse all graphic novels included in the Guardian and Observer’s best books of 2023 visit guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.