Author A.J. West on the queer riot that history forgot: ‘Nearly three centuries on, it’s a spirit we can still identify with’

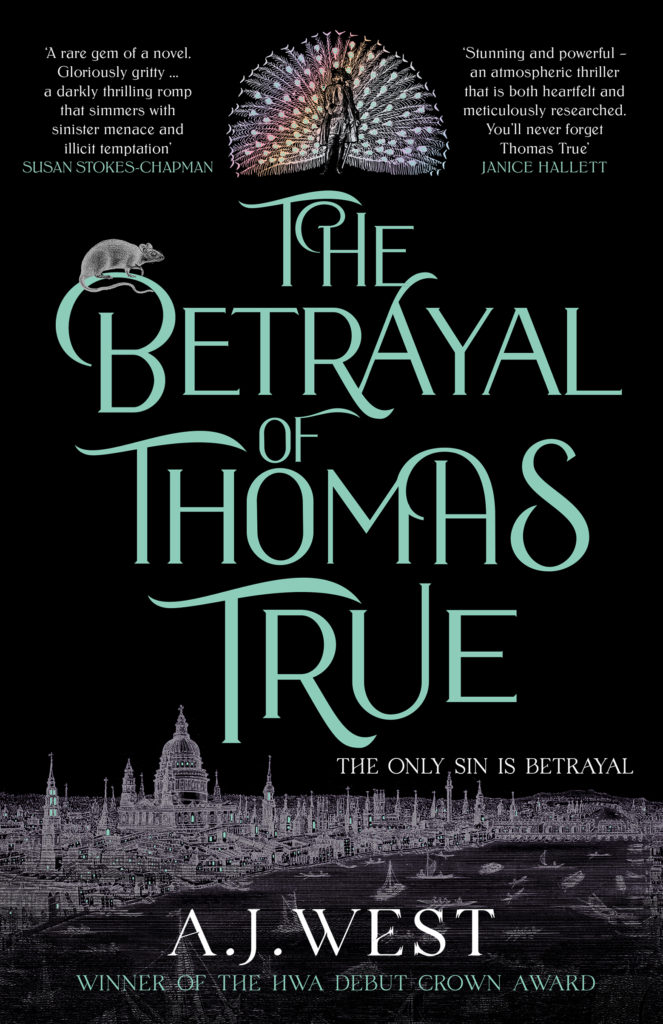

Sunday Times bestselling author A.J. West weaves a tale of intrigue and forbidden desire in his latest novel, The Betrayal of Thomas True, available from 4 July.

Set in the shadowy heart of 18th-century London, the story plunges readers into a world of clandestine societies and hidden queer subculture, as the titular protagonist navigates treacherous alliances and dark secrets in the search for truth and love.

While researching for this work of fiction, West discovered a remarkable true event that may well be Britain’s first recorded queer riot. Here, he shares with Attitude this forgotten story of defiance and solidarity that helped inspire his novel.

It is 2 May 1727, and the atmosphere on Catherine Street, just off the Strand, is tense. An event is about to take place that is a significant milestone in gay history, yet it’s been all but forgotten.

A man in his early fifties is brought to the pillory; his hands and neck are locked into the wooden framework, his back bent forwards, while constables stand around him in anticipation of a riot.

Something highly unusual is taking place. Not the pillory itself; these are commonplace across London. Prisoners prosecuted for minor crimes are often punished with a few hours in the stocks, where they are subjected to whatever the mob throws at them — excrement, rocks, dead animals and more. It’s a humiliating test of any convict’s endurance, but this shackled wretch is in grave danger, and the events of the following hour — indeed, the next few minutes — are destined to play a grim part in his eventual death seven months later.

The pillory: a stage for London’s first queer riot

How his fortunes have changed. The prisoner is Charles Hitchin and he holds the title of Under Marshal of the City of London, responsible for supervising watchmen long before the establishment of a police force. His qualifications for the role? None were required. In fact, he was nothing more than a cabinet maker before he bought his title and position for the considerable sum of £700. It must have seemed like a wise investment at the time because, although the role itself offered little in the way of compensation, it allowed Hitchin to run illegal rackets in collusion with the criminal underworld. He blackmailed thousands of cutpurses, thieves and every type of villain, extorting them for protection money and seizing their stolen goods.

Charles Hitchin: from cabinet maker to corrupt Under Marshal

He was, to put it bluntly, a crook, but an outwardly pious one because, in addition to his work as Under Marshal, he happened to belong to an organisation called The Society for the Reformation of Manners. This self-appointed religious group of righteous vigilantes was responsible for a network of paid informants and enforcers which spread across the city, supposedly suppressing profanity, immorality and other lewd activities. Sponsored by the clergy, business leaders, the gentry, the judiciary and politicians, they took pains to bribe people into turning traitor, effectively forcing victims through the courts to be tortured, pilloried and, in a few cases, hanged.

The Society for the Reformation of Manners: vigilantes of morality

Naturally, Hitchin’s Society associates took an interest in the mollies or ‘he-whores’ of the City of London. These men cavorted in women’s gowns and assumed the language and behaviours of milkmaids, shepherdesses, tavern wenches and harlots.

In modern terms, these were gay or queer men, who existed in an underground world of secret coffee houses, boarding houses and makeshift taverns, where they could assume alter-egos, subvert gender roles, drink, dance and fuck. Blow jobs, by the way, were seen as filthy back then, even by cudgel-lovers. This was perhaps understandable in a time before shower gel, deodorant and antibiotics. Pustules, rashes and pungent slimes were commonplace on cocks, so it was wise to keep them at arm’s or bottom’s length, while lube was nothing more advanced than spit.

Inside the molly houses: Georgian London’s secret queer subculture

Hidden away from ridicule and the very real threat of imprisonment and execution, Georgian ‘pretty fellows’ were free to ‘marry’ (fuck) each other in rooms known as ‘chapels’, often cheered on by their enthusiastic spectators in the parlour beyond. This subversive and satirical sub-culture mocked the church and emulated ‘doxies’ and ‘whores’, while allowing farriers, butchers, masons, apprentices, guardsmen and all sorts of men to have a play with each other’s tools, while experimenting with their own identities. They initiated each other with names like Pomegranate Molly, Dip-Candle Mary and Old Fish Hannah.

The molly houses were places for defiance as well as lust, and the men who frequented them did so knowing their livelihoods, reputations, souls — even their lives — were at risk. For years, they’d been allowed to hide in plain sight, even wearing their molly garb in public in some cases, but pride can so often lead to prejudice, and an increasing number of raids were being carried out by the Society for the Reformation of Manners. Those convicted for sodomy, particularly bottoms, could be hanged at Tyburn. Meanwhile, lesser ‘offences’ like hand jobs or even kissing could lead to a spell in the pillory, if not capital punishment.

The dangerous double life of Charles Hitchin

And so we return to Charles Hitchin. Despite being a member of the Society for the Reformation of Manners, he had been concealing a secret, as the details of his trial at the Old Bailey reveal.

The queer historian Rictor Norton recounts in his book, Mother Clap’s Molly House: “On 29 March 1727, Hitchin met Richard Williamson at the Savoy gate and asked him to have a drink. They went to the Royal Oak in the Strand ‘where, after we had two Pints of Beer’, according to Williamson, Hitchin ‘began to make use of some sodomitical indecencies’. They then went to the Rummer Tavern where, while imbibing two pints of wine, Hitchin ‘hugg’d me, and kiss’d me, and put his Hand—’.

Court records from the Old Bailey often redacted lewd details, but it isn’t very hard to fill in the blanks here. They fucked. Under Marshal Hitchin was himself a practising homosexual. A servant later told the court that Hitchin was well known at the tavern, often frequenting it with soldiers and ‘other scandalous fellows’. It seems Richard Williamson woke up the next morning full of regrets and confessed all to a relative, so the pair sneaked back to the bedchamber, where they spied Hitchin having sex with another man. In his subsequent trial, Hitchin was acquitted of sodomy but found guilty of the lesser offence of attempting buggery, and sentenced to a fine of 20 pounds, as well as six months behind bars and a spell in the pillory.

Homosexuality in Georgian London

In Georgian London, the notion of homosexuality — and sodomy in particular — wasn’t just taboo; it was seen as subhuman, the most egregious sin against God imaginable. Meanwhile, the leading thinkers of the day, including the celebrated novelist, journalist, spy and pamphleteer Daniel Defoe depicted mollies not so much as men attracted to other men, but as a sort of infestation, liable to corrupt any right-thinking Christian in its vicinity. In his periodical A Review of the State of the British Nation, Defoe responds to a spate of molly arrests in 1707, describing those pilloried as ‘bestial’ and ‘hellish creatures’. He campaigned for mollies to be punished out of the public eye to spare good men and women from their infectious crimes, concluding: “I believe, every good Man loaths [sic] and pities them at the same time … So in their Crime they ought to be … spued [sic] out of Society, and sent expressly out of the World, as secretly and privately, as may consist with Justice and the Laws.”

Daniel Defoe and the demonisation of mollies

It has been claimed in recent years that Defoe might himself have been gay or bisexual, but there’s no real evidence for the theory, only somewhat imaginative speculation. The suggestion has been widely discredited, and if he was hiding a secret behind his wife and five children, he certainly showed no sympathy for the mollies.

Nor did the 1700s satirist Ned Ward, who described a ‘Gang of Sodomitical Wretches’ in his History of the London Clubs, and gleefully mocked the men for their dress and behaviour: “There are a particular Gang of Sodomitical Wretches in this Town, who call themselves the Mollies, and are so far degenerated from all masculine deportment, or manly Exercises, that they rather fancy themselves Women.”

He goes on to describe the mollies gossiping, extolling the virtues of their husbands, and even giving birth to a wooden ‘jointed baby’. He finishes by celebrating the routing and ‘open punishment’ of the mollies by the agents of the Society for the Reformation of Manners. Such popular accounts ensured that gay men were reviled by women as well as men, with female sex workers particularly scathing in their disdain for ‘buggerantoes’ and ‘he-whores’ who stole their business from them.

Pillory showdown

Back on the strand, constables are shifting nervously in the dust, readying themselves for a fight to the din of a baying crowd. The racket rings out against the sides of the tottering buildings, drowning out Charles Hitchin’s prayers. The crowd are determined to mete out their most vitriolic punishment for his disgusting acts. His enemies want to enjoy his terror and his pain. They want to lust in it. After all, his pillorying promises to be one of the most thrilling in recent memory.

Their violence, however, is being thwarted. The side streets surrounding the raised wooden platform have been barricaded with carts and coaches, impeding the riotous crowds. That’s strange enough, but there’s something else peculiar about this scene, because the ‘friends and brethren’ who have blocked access to the site of the Under Marshal’s punishment are not members of the Society for the Reformation of Manners, nor are they associates from his office, nor are they members of his family. They are criminals themselves, loyal to their master in spite of his sins. And a good number of them are mollies.

Unexpected allies

This goes some way to explaining the rage of the harlots who are now clambering over and in between the coaches and carts circling Hitchin in the pillory. They have broken through the barricades with their various missiles swaddled in their skirts, ready to pelt Hitchin as he whimpers and rattles in the pillory, knowing what’s to come. And so it does. There is a violent confrontation, the mollies and villains on one side; the angry women and men on the other. For the next half an hour, a battle rages with much blood spilled as the mob tries to attack Hitchin and his friends and the police officers do their futile best to keep them at bay.

Eventually, Hitchin is let down from the pillory, covered in filth, his britches and nightgown torn away to reveal his naked body. He collapses in a faint and is dragged away to begin a gruelling stint in the infamous squalor of Newgate Prison. He was released after six months of incarceration, when he sold his position as Under City Marshal for £700. He died only a few weeks later, likely due to the injuries he received in the pillory.

Aftermath

Queer historians have suggested that Hitchin’s pillorying could well be the first recorded queer riot in history, predating the Stonewall Uprising by more than two centuries. It’s extraordinary to think that back then, in a fervently religious age, and even though Hitchin was a nefarious individual, gay men rose up to defend one of their own. We’ll never know the full story, or understand why Hitchin deserved their loyalty, but for some reason, those mollies decided to make a stand and revolt. Nearly three centuries on, it’s a spirit we can still identify with.

The Betrayal of Thomas True is published on 4 July by Orenda Books. Click here to order.

The post Author A.J. West on the queer riot that history forgot: ‘Nearly three centuries on, it’s a spirit we can still identify with’ appeared first on Attitude.