Andrew Scott: ‘I didn’t hide being gay – it just didn’t come up’

Andrew Scott has a curious kind of fame. Being with the 47-year-old “hot priest” from Fleabag in a busy London hotel at night reveals both sides of it. The Irishman can pass unnoticed by some, while other passersby nudge each other as if to say, “Look! Star in our midst.”

When he played Hamlet at the Almeida in 2017, a group of young, mostly female fans would wait at the stage door for him every night, drawn by the devilish Moriarty he had played to Benedict Cumberbatch’s Holmes in Sherlock. Does he still have those fans? “I do, yeah,” he says. “I find that really moving. That people would come from not just England, but from all around the world. It’s the power of those kind of television shows.”

He is handsome, suited, glamorous in a way that contrasts with a sort of guarded innocence; the two meet and combine in a glittering smile. Phoebe Waller-Bridge – who created and co-starred in Fleabag opposite Scott – described him as having the charisma of 10 people rolled into one. It’s not hard to see why his sensitive, introspective Hamlet was such a revelation. But there’s rarely a role that doesn’t also reveal his wit, from his seen-it-all lieutenant in Sam Mendes’s 1917 to his libertine Lord Merlin in the BBC’s otherwise underwhelming Nancy Mitford adaptation, The Pursuit of Love.

At the back end of last year, he performed all the roles in Vanya, Simon Stephens’s reimagining of Chekhov’s classic play into a one-man show, a theatrical feat that had Scott wondering each morning how he could possibly get up and do it again. “You wake up, and you have to psych yourself up for around six in the evening, and then you go through these huge emotional peaks and troughs, and by the time you get back home, you’re exhausted, but you’ve still got all this adrenalin going,” he says. “And then you wake up again, and you’re just completely spent.

“It was an amazing thing to do,” he adds, “and absolutely f---ing mental.” In one scene, playing both a weary-yet hot doctor and a fading film director’s glamorous young wife, he shared a sexy embrace – with himself. “Oh my God, it was so weird … it was always incredibly, massively silent in the room. You could hear a pin drop.”

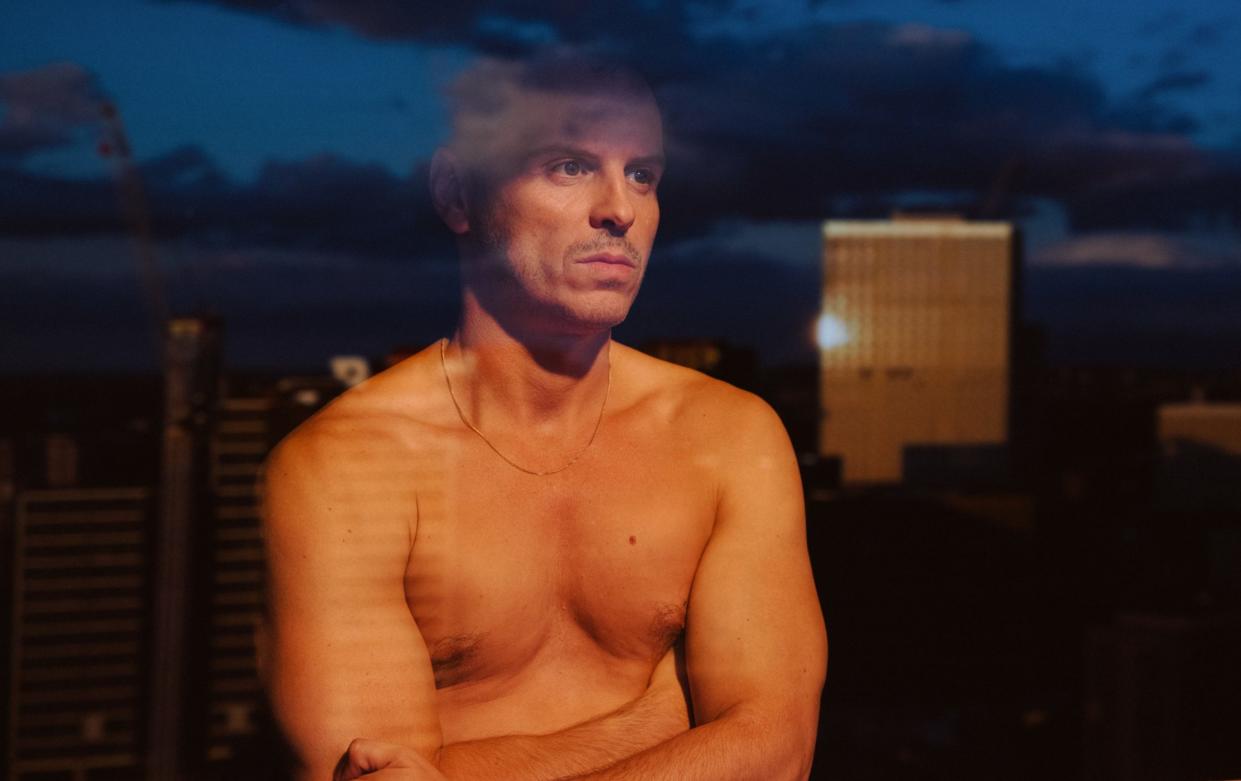

The play was filmed for National Theatre Live and will be shown in cinemas next month. First, though, comes the release of Andrew Haigh’s subtle, mysterious and very moving new film All of Us Strangers. In it, Scott plays Adam, a screenwriter who lives alone in a mostly unoccupied high-rise London apartment building, from which he looks down over the city without being a part of it. He has begun writing about his parents, who died in a car accident when he was a boy, when sex and romance push their way into his world in the shape of Harry, played by Paul Mescal, of Normal People and Aftersun fame.

There are tremendous supporting performances from The Crown’s Claire Foy and Billy Elliot star Jamie Bell as Adam’s parents, whom he sees and speaks to as if they were still alive. This week, the film was nominated for six Baftas, including acting nods for both Foy and Mescal, though Scott – who already had a Golden Globe nomination under his belt – missed out. He doesn’t like talking about awards, anyway. “The only thing that I really genuinely care about is how much the movie’s having an effect on people,” he says. “I just really hope people go and see it.”

The film – which is a loose adaptation of the ghostly 1987 novel Strangers by Taichi Yamada, the Japanese author, who died in November – deals with grief, family and the afterlife. Its elusive narrative contrasts with a pin-sharp evocation of time and place, mirrored by Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch’s haunting score and the unmistakable 1980s hits of Frankie Goes to Hollywood and the Housemartins. “It’s not necessarily autobiographical, but [Haigh’s] emotional biography is in there,” Scott says. The actor, too, tried to bring as much of himself to the character as possible – a process which he has described as “not acting, not pretending to be somebody else”. “When I read the script, I felt I didn’t want to go and make up a backstory for the character that wasn’t my own.”

Small clues in the film highlight this: Adam says, for example, that his grandmother took him to Dublin after his parents’ death. Scott grew up in the Irish capital, the middle child of three, in a middle-class family, with an elder and a younger sister; he went to Trinity there, too, but dropped out to act at the Abbey Theatre. “It isn’t my autobiography either,” he stresses. “But there are certain things about that struggle, you know, he says it in the script – it doesn’t take much for you to go back to that place where you felt fearful and scared.”

Scott came of age in the 1990s, when the widespread public paranoia about Aids was beginning to recede, but for the greater part of his teenage years, homosexuality was still criminalised in Ireland. Returning to his younger self imaginatively, he notes, creates a conflict for the character Adam is now. “He doesn’t really want to come out to his mother in his 40s, to have to explain himself in the way that he might have done when he was 16. There’s a kind of dignity there that he’s trying to hold on to, so he tries to sort of tell her in passing this enormous, significant part of his personality.”

For Scott, the experience of acknowledging his own sexuality to friends and family was “much more important” than when he did so in public, only broaching the subject in interviews for the first time in 2013 while promoting the film Pride. “It wasn’t that I was going, I really want to hide this,” he says. “It just didn’t come up, but then I started to do more interviews, and I thought, it just feels right.”

Privately, he notes, “some people aren’t lucky enough to be accepted by their family, but one of the things that I think that gave me, actually risking something and telling somebody who you are, whatever that might be – in my case, it was my sexuality – but to be able to say that to your parents and go, ‘I wonder, would they love me no matter what?’, and to find that they do, it’s something that I got very early in my life.”

Haigh has said that it was important to him that a gay man play the role. “There’s so much nuance that I was trying to get to,” he told the audience at a New York screening, “I didn’t want to have an endless conversation with somebody who’s trying to understand it.”

I ask if Scott has a view about actors having the lived experience of the characters they play. “I think to try and answer that question in some sort of succinct fashion is really dangerous,” he says. “The thing that we have to be careful about is extremism. The question that I would ask if someone were to make a film about my life – which I can see would not, you know, get very much funding – would be: do I want just gay actors to be considered to play me?

“And I suppose I’d have to say, well, what are my other attributes that people can play? Of course, my sexuality is important, but so are many other attributes, and sometimes I would say that they’re more important.

“Also, you know, people’s sexuality is fluid. I have friends who are in relationships with people of the same sex who used to be in relationships with people of the opposite sex. So how do you legislate for that? I don’t believe that you should have to trade on your sexuality in order to get employment.”

Sex is important to the film, though. A scene in which Mescal’s Harry knocks at Adam’s door and tries to invite himself inside has a transgressive quality. When Adam refuses to let him in, Harry asks, “Do I scare you?” Is that what we recognise as “sexy”? “Yeah, there’s the element of risk, isn’t there,” says Scott. “Because falling in love is scary. And I like the fact that the film represents love in that way, that it’s pretty dark and complicated. It isn’t this walk in the park that some movies would have us believe.”

He has said in the past that the straight community could learn from the gay community’s greater openness about sex. “I think if you’re operating outside the so-called norms of society, then you have to really embrace who you are,” he says. “And I think there’s a huge amount of emancipation from shame that’s very important. As I grow older, the thing that I value is being able to talk with gay friends about our experiences in a very open way.”

One of the things he draws from those frank discussions, he says, is that “being your authentic psychosexual self doesn’t preclude you from being a kind, honourable member of the community”.

In a recent interview, Mescal was quoted as saying that Scott had told him that “the only thing you’re left with after love is grief”. Mescal concluded that it was “a bleak thing, but I think it’s just a fact” and it was widely taken to be a reference to the 27-year-old’s break-up with singer-songwriter Phoebe Bridgers.

“I suppose grief is the price you pay for love, isn’t it,” Scott says, quietly. “I certainly have grief in my life about love.” He doesn’t want to get into it too much, he says, or talk about his current romantic situation, although he was previously in a long-term relationship that ended some years ago.

There is a little refrain in the film about Adam having to fend off questions about why he didn’t have a girlfriend – something that happened to Scott, too, he says. “I guess the world is a place where the assumption is that everybody is straight. I think if we all just paused a little bit, and were able to not make that assumption, it would do a huge amount of good. Because that’s the thing that leads to an insidious sense of a lack of belonging.”

He talks of “the accidental cruelty of families – something that I really think is very alive in the film – the fact that our families can say things that are pretty brutal, unseeing and fearful, but at the same time, they really love you more than any other people in the world”.

The film highlights the loneliness of its main character, in an age when society is said to be experiencing an epidemic of loneliness. Scott notes that “you can experience loneliness sitting on the couch with somebody else. To me, the most important thing is to connect to lots of different types of people.

“I still really like people,” he adds, “and one of the things that I’m anxious to protect is my ability to be able to walk down the street, and not feel like, ‘Oh, here’s a person coming up to me, and it’s going to be tiresome’. I don’t want people to become the enemy”

We chat about Fleabag, and perhaps its most famous line, the priest’s response to Waller-Bridge’s character when she tells him that she loves him: “It’ll pass.” Scott says that “when I first read that line, I remember thinking, ‘Is that a cruel thing to say?’ But actually, I think it’s incredibly compassionate. Because of course it does. It may not pass without a great deal of pain. But it does pass.”

He’s been cast in Netflix’s forthcoming series Ripley, playing Patricia Highsmith’s dangerous con artist Tom Ripley, opposite Johnny Flynn as Dickie Greenleaf. After swearing off glamorous baddies for a while, post-Sherlock, what tempted him to take on one of the iconic villains of our time, one already played on screen by Alain Delon, Dennis Hopper and Matt Damon?

“Well, I wouldn’t say that he’s a villain,” Scott says with a flashing smile. “I don’t think of him in any way like that. He’s an antihero …” He’s a serial killer, I suggest … “OK, fine, he’s a serial killer,” he says. “I did find it dark to play it, definitely, but I don’t, I don’t, I don’t …” he shifts unwillingly. “I suppose I was happy to consider that Moriarty was a villain, even though I probably was a bit resistant even to calling him that.”

He pauses. “The only interesting thing is trying to find the humanity in a character, even though he does extraordinary things.”

All of Us Strangers is in UK cinemas from January 26