21 ancient wonders that you are BANNED from seeing

Off-limits treasures

FredChimelli/Shutterstock

The world is full of ancient wonders, but sadly many cultural treasures are off limits to international visitors. Whether they're out of bounds due to their location in areas of conflict or dangerous structural instability, or simply because they are extremely hard to get to, we take a look at some age-old treasures that you’re highly unlikely to ever see in person…

Palmyra, Syria

Waj/Shutterstock

One of the many archaeological treasures irrevocably and intentionally damaged during Syria’s ongoing conflict, the ruins of the ancient city of Palmyra rise out of the Syrian Desert in Homs province. The historic Silk Road hub has been off-limits ever since it was twice occupied by and desecrated by Islamic State fundamentalists. Among the wonders destroyed were the temple to Mesopotamian god Bel and the Arch of Victory.

Palmyra, Syria

Waj/Shutterstock

Dating from the 1st to the 2nd century, the desert city’s art and architecture reflects the traditions of several civilizations, marrying Graeco-Roman techniques with local traditions and Persian influences. Already a wealthy caravan oasis, the settlement came under Roman control in the mid-first century AD, consolidating its power as a key city connecting the east with the Mediterranean. Efforts to reconstruct parts of the site began in 2021, but the country remains extremely unstable and progress is slow.

Krak des Chevaliers, Syria

WitR/Shutterstock

With its formidable defenses and impregnable position, this colossal hilltop castle is one of the finest crusader castles still standing. Along with another nearby medieval fortress, the more dilapidated Qal’at Salah El-Din, it forms one of Syria’s six World Heritage cultural sites, which are all on UNESCO’s endangered list.

Krak des Chevaliers, Syria

xyuzu2020/Shutterstock

Originally built for the Emir of Aleppo in 1031, Krak des Chevaliers was later commandeered and extended by the military order of the Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem as the crusader forces battled Muslim armies in the region. The mighty limestone structure was occupied by anti-government forces several years ago and suffered some irreparable damage. The UK and US governments advise against all travel to Syria under any circumstances.

Leptis Magna, Libya

BigRoloImages/Shutterstock

The imposing ruins of Leptis Magna, on Libya’s Mediterranean coast, are considered among the finest remains of a Roman city in the world. Buried for centuries under the sand, it was said to be one of the most beautiful cities in the Empire. However, its history stretches back far earlier – it was most likely founded by the Phoenicians around the 7th century BC. Sadly, the site is strictly out of bounds to international visitors due to ongoing conflict and political instability – the UK Foreign Office (FCDO) and the US State Department have both advised against all travel to Libya for almost the last decade.

Leptis Magna, Libya

Norman Krauss/Shutterstock

The handsome harbor city reached its height during the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD. It was even the birthplace of a Roman emperor, Septimius Severus, who ordered the construction of many of the larger structures that remain here. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1982, the sprawling remains were added to the international heritage body’s danger list in 2016 along with Libya’s four other UNESCO sites.

Sabratha, Libya

tourdottk/Shutterstock

Famed for its vast amphitheater, Sabratha was a Phoenician trading post rebuilt by the Romans in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD and an important trade center on the trans-Saharan caravan route. As well as the vast theater, the ruins include several temples, a forum, part of a colonnade, fountains and public baths. This jewel of the Roman Empire was assessed as endangered by UNESCO in 2016, after the site was damaged and looted during fighting between rival militia.

Simena, Turkey

Lestertair/Shutterstock

Destroyed by a series of earthquakes in the 2nd century, the remains of this Lycian civilisation are tantalizingly out of reach to visitors today. While some of Simena’s incredible structures, including ornate tombs, rise above the water level and can be seen from dry land, much of the remains of the sunken ancient city lie beneath the surface off the uninhabited island of Kekova. Diving and snorkeling are banned to protect the fragile ruins, with the region categorised as a Specially Protected Area, though some tour boats are allowed to pass by slowly.

Sana’a, Yemen

javarman/Shutterstock

Rising spectacularly out of a mountain valley, Yemen’s capital Sana’a is one of the world's oldest cities, having been inhabited for more than 2,500 years. Its UNESCO-listed old town is notable for its rammed earth-built tower houses with striking geometric patterns and high clay walls that encircle numerous mosques, including the 7th-century Jami’ al-Kabir, ancient palaces and baths. But due to the devastating civil war, governments from all over the world advise their citizens to stay away from Yemen.

Sana’a, Yemen

MOHAMMED HUWAIS/AFP/Getty Images

Many of the city’s ancient buildings have been damaged by the armed conflict and left in a state of severe disrepair. The old town was placed on UNESCO’s List of World Heritage in Danger in 2015, with the body citing serious damage to the neighborhood of al Qasimi, near the famous urban garden of Miqshamat al Qasimi. The 12th-century al-Mahdi Mosque was also damaged. "The majority of the colorful, decorated doors and window panes characteristic of the city’s domestic architecture have been shattered or damaged,” said the body.

Baalbek, Lebanon

iryna1/Shutterstock

The Phoenician city of Baalbek, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, has long been one of Lebanon’s prime tourist attractions, but visiting the area is highly inadvisable at present. Situated close to the Syrian border, many governments warn their citizens against exploring the impressive ruins, which contain some extraordinary structures from when the city came under Roman control in the 1st century.

Baalbek, Lebanon

FredChimelli/Shutterstock

Named after Baal, the Phoenician deity, the site was known by the Romans by its Greek name, Heliopolis (City of the Sun). The sprawling complex of colossal temples and well-preserved architecture is described as “one of the most impressive testimonies of the Roman architecture of the imperial period” by UNESCO. It was one of the most celebrated sanctuaries of the ancient world and the remains of its mighty Temple of Jupiter are among its most impressive out-of-reach treasures.

Tigray, Ethiopia

Framalicious/Shutterstock

Ethiopia's northern highland region of Tigray, near the Eritrean border, is home to numerous cultural and religious treasures. Up until November 2022, when a truce was agreed, it had seen horrific violence during a period of civil war. As well as the UNESCO archaeology site of Aksum, its remote rock-cut churches and monastery of Debre Damo (pictured) were under threat. In January 2021, it was reported that the isolated monastery, which dates back to Aksumite times and the 6th-century reign of King Gebre Meskel, was attacked and looted. The UK government advises against all travel to the entire Tigray region, with the US asking citizens to reconsider travel to Ethiopia.

Aksum, Ethiopia

Framalicious/Shutterstock

The capital of the ancient Aksumite kingdom, Aksum was said to be the birthplace of the biblical Queen of Sheba, who traveled to Jerusalem to visit King Solomon. Their son Menelik I allegedly brought the Ark of the Covenant (containing the stone tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments) to the city where they remain. They are said to lie hidden in the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion in modern-day Aksum and guarded by Ethiopian Orthodox monks. The most sacred place for all Orthodox Ethiopians, the church was also the scene of an appalling massacre in the recent civil war.

Ciudad Perdida, Colombia

Joerg Steber/Shutterstock

While it’s possible to visit the so-called Lost City, which was uncovered in the thick tropical forest on the northern slopes of Colombia’s Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in the 1970s, it is no mean feat. It's thought to have been built by the Tairona people more than 1,000 years ago and getting to the remote archaeological site involves a six-day hike through dangerous terrain and ends with a thigh-burning 1,200-step climb up to the ancient citadel that was carved into the mountainside.

Ciudad Perdida, Colombia

Joerg Steber/Shutterstock

Known locally as Teyuna, the site can only be visited with a licensed guide who will lead travelers on the 27-mile (43km) trek up mountains and across rivers, all in extremely hot and humid conditions. A group of tourists hiking to the Lost City was kidnapped in 2003, but now, unlike some areas of Colombia which come with a very high risk of crime and terrorism, the Magdalena department is deemed safe for tourism.

Agadez, Niger

Homo Cosmicos/Shutterstock

Security issues mean the many ancient wonders of Agadez in Niger are out of bounds for tourism. The FCDO advises against all travel to the city, which sits on the southern edge of the Sahara Desert, due to political unrest, while the US State Department urges would-be travelers to Niger to reconsider. Among the treasures in the city's historic center, which dates from the 15th and 16th centuries, is the mud minaret of the Great Mosque of Agadez. It is the highest mud brick structure in the world.

Kibyra, Turkey

Mete Caner Arican/Shutterstock

The huge monumental structures of ancient Kibrya in southwest Turkey’s Burdur Province are little-visited but open to tourists. But an incredible Medusa mosaic, which was only discovered among the ruins of the ancient Greek and later Roman city in 2009, is one wonder that’s mostly off limits. The delicate tiles were found in the bouleuterion (which was used as a courthouse, theater and parliament house) and are covered for nine months of the year to protect them from the elements.

Ashur, Iraq

Véronique Dauge/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

First established in the 3rd millennium BC, the ancient city of Ashur is one of Iraq’s many ancient treasures that are unlikely to receive international visitors anytime soon. It was once an important center of trade and became the first capital of the Assyrian Empire between the 14th and 9th centuries BC. It was also the religious capital of the Assyrians, associated with the god Ashur, and the burial place for its kings. Ashur was sacked by the Babylonians, but revived during the Parthian period in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD.

Ashur, Iraq

Véronique Dauge/ Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

Located near the modern-day city Qal'at Sherqat, Ashur’s excavated remnants were added to UNESCO’s danger list in 2003, due to the prospective construction of a dam that would have flooded the site as well as its location in a highly volatile area. More recently, the site has been endangered by the Islamic State, with extremists severely damaging Iraq’s ancient archaeological and historical monuments, including the ancient Assyrian cities of Nineveh (the empire's oldest city) and Nimrud. The UK and US governments advise against all travel to Iraq under any circumstances.

Hatra, Iraq

Staff Sgt. JoAnn Makinano/Wikimedia/Public domain

The fortress city of Hatra, which dates back to the days of the Parthian empire in the 3rd or 2nd century BC, was the capital of the first Arab Kingdom. It's known for its mighty walls and towers, which helped it withstand two Roman invasions in the 2nd century AD, and has numerous temples and sculptures dedicated to gods including Apollo and Poseidon. The important archaeological site in northern Iraq was taken by Islamic State in 2015, who used sledgehammers and guns to destroy carvings and statues. It is in the process of being restored.

Timbuktu, Mali

Peter Langer/Zuma Press/PA Images

A hub of Arab-African trade and ancient center of Islamic learning (it established one of the world’s earliest universities in the 12th century), Timbuktu has a wealth of historic and spiritual buildings. Founded by Tuareg nomads around 1100 AD, the desert city flourished due to its trade of salt and gold. But today it’s threatened by the encroachment of the desert sands and prolonged armed conflict. After the 2012 military coup, Islamic fundamentalists destroyed some of Timbuktu’s ancient mausoleums and manuscripts.

Timbuktu, Mali

Peter Langer/Zuma Press/PA Images

The city in northern Mali is famous for its three magnificent mud-and-timber mosques – Djingareyber, Sankore and Sidi Yahia – which are symbols of its former glory. They date to the 14th and 15th century but their fragile earthen structures need continuous restoration. Ongoing conflict and risk from terrorism means that FCDO advises against all travel to Timbuktu (and most of the rest of the country), while the US State Department instructs citizens not to visit the country at all.

Laas Geel, Somaliland

Janos Rautonen/Shutterstock

Decorating several caves in Somaliland, the well-preserved rock art of Laas Geel is some of the best in all of Africa. A host of world governments advise against traveling to Somalia and the self-declared independent Republic of Somaliland due to security risks, so the age-old paintings are unlikely to get many international visitors in the near future. Ranging from 5,000 to 10,000 years old, the images in the rocky shelters depict scenes of pastoral life and include animals that no longer inhabit the region, such as giraffes.

Minaret of Jam, Afghanistan

David Adamec/Wikimedia/Public domain

With its spectacular landscapes, rich mix of cultures and ancient history, Afghanistan is an alluring travel destination that has been largely inaccessible for decades, and became even more so when the Taliban returned to power in 2021. One of its most significant monuments is the medieval Minaret of Jam, which is tucked into a plunging river valley between soaring mountains. Dating to the 12th century, the leaning tower was built by the great Ghurid Sultan Ghiyas-od-din and is lauded as a fine example of the architectural styles of Central Asia's Islamic period.

Abu Mena, Egypt

Peter Langer/Zuma Press/PA Images

The archaeological site of Abu Mena, near Alexandria, houses the remains of an early Christian holy city, which was built over the tomb of Saint Menas of Alexandria, who was martyred in the 3rd century. Sadly, the foundations of some of the great ruined buildings have collapsed thanks to changes in the water table. The fragile site remains very unstable and it was inscribed on UNESCO’s endangered heritage sites list in 2001.

Pyu ancient cities, Myanmar

Benjamas Pech/Shutterstock

The political situation in Myanmar, which has been in a state of armed conflict ever since a military coup in 2021, puts its beautiful temples, palaces and historic monuments out of bounds for now. This includes the ancient Pyu cities of Sri Ksetra, Halin and Beikthano in the north, which were declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2014 and have some of the world's most ancient Buddhist temples. The Pyu dynasty was at its peak from BC 200 and 900 AD.

Pyu ancient cities, Myanmar

PHATSAWAT/Shutterstock

The three brick-walled and moated cities remain only partially excavated, but what has been uncovered includes the remains of palace citadels, burial grounds, water management features and monumental brick Buddhist stupas, such as the Payama Stupa at Sri Ksetra, pictured in the previous slide.

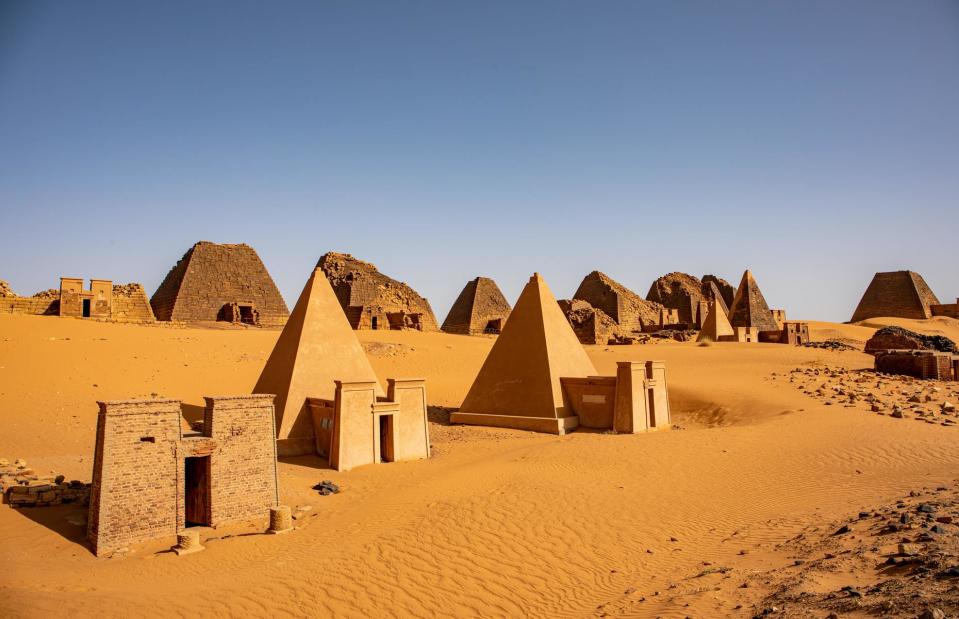

Meroë pyramids, Sudan

evenfh/Shutterstock

It might have more ancient pyramids than Egypt but very few people know about, let alone will get to visit, Sudan’s extraordinary collection of ancient wonders. Lying on the east bank of the Nile, northeast of capital Khartoum, nearly 200 pyramids lie scattered among the dunes at Meroë. They were built by the rulers of the ancient Kushite kingdom, a major power in the ancient world from the 8th century BC to the 4th century AD. The small (in comparison to Giza's monumental pyramids) but impressive monuments are off the table for tourism thanks to political instability and conflict in the east African country.

Naqa, Sudan

Thomas Markert/Shutterstock

To the west of Meroë lies the archaeological treasures of Naqa, an ancient city that was part of the Kushite kingdom. Known for its well-preserved temples, Naqa's key features are the temple of Amun and the temple of Apedemak (or Lion Temple), which is prized as a classic example of Kushite architecture. It also has a Roman kiosk (pictured), lying just to the east of the Lion Temple, which reveals Pharaonic Egyptian, Hellenistic and Kushite influences in its architecture and decorative elements.

Now check out these ancient mysteries we don't know the answer to