Alison Steadman: ‘The older I get, I don't want to be alone’

In 1993, Alison Steadman’s mother, Marjorie, ‘feeling very unwell’, as Steadman puts it, was admitted to hospital for tests. She was on her own on the hospital ward, Steadman remembers, when the consultant came to her bedside. ‘He said, “I’m afraid it’s bad news; you’ve got terminal pancreatic cancer and there’s nothing we can do.” And then he walked out.

Steadman slowly shakes her head, still aghast. ‘My mother said to me, it felt like he’d got hold of her and thrown her against the plate-glass window in the ward.’ Then the consultant called in Steadman and her two sisters to give them the news.

‘I thought, I’m going to have a go at him; this isn’t good enough. He obviously was a brilliant guy, but he had no idea how to talk to people. ‘He said, “I have to tell you, your mother’s got between two and six months to live.” I said, “Under no circumstances do you tell her that, because if you do, she’ll be finished.”

‘When we got back home, my sister said, “You’re the actress; you take care of it.” My mother looked at me and asked: “Any hope?” I couldn’t tell her what the doctor said. And I said, “What a prat that guy is. He may be a brilliant surgeon but he’s not God! How does he know how long you’ve got to live? What you’ve got to do is just take care of yourself and enjoy your life.”

‘Afterwards, my sister hugged me and said, “You deserve an Oscar for that.”’Steadman laughs. Marjorie would live for another two years. She was put in the care of the Marie Curie Hospice in Liverpool.

‘And they were great with her,’ says Steadman. ‘As soon as we walked through the door at the hospice there was a huge sense of relief. There was none of this, “Sit down, I’m afraid we’ve got some bad news to tell you…”

‘The first time she went, she’d put one of her best dresses on, and when she came back she said, “What a lovely doctor I met; do you know the first thing she said to me was, ‘I love that dress…’” And straight away, her spirits were lifted,’ continues Steadman.

‘Of course, she had her ups and downs, but they really did do their best. She was at home, but sometimes she’d need time in there for respite care.

‘There were times she wasn’t well at all. But the atmosphere was great. They’d come round in the evenings with a trolley with sherry and wine, and say, “Anybody want a drink?” Most people weren’t well enough to have a drink, or didn’t want one, but it was the fact of it. It made people alive.

‘In the hospital, when she couldn’t eat, they’d just dump the food down and walk away, and if she didn’t eat it, they’d clear it away.

‘At Marie Curie, shortly after she arrived, this lovely young male nurse came over and he knelt down and took her hand and said, “Now Marj, can we get you anything you fancy? How about a bowl of custard or a boiled egg?” It’s how I would have treated my mum, with a bit of care.’

Steadman has been an active supporter of Marie Curie for more than 20 years, and she had absolutely no hesitation in accepting when the charity asked her in 2017 whether she would be an official ambassador.

Since then, she has lent her name and time to various Marie Curie campaigns, attending events and recording voiceovers for television and radio ads. During lockdown she hosted a Gavin & Stacey quiz on Zoom, which raised more than £60,000.

‘I think it’s so important that we have an organisation like Marie Curie, instead of just hospitals where you’ve got to go in and be treated like AN Other,’ says Steadman. ‘So I’ve been very proud to support them, and I hope it would have made my mum proud, too.’

We are sitting in a Greek restaurant in north London, around the corner from a studio where for the past two hours Steadman has sat uncomplainingly, putting on her best face for our photo session. ‘I’m dying for a cup of tea’, she says, as the waiter materialises at our table, bearing a tray of mezze.

Steadman is the youngest of three sisters. Her father George worked as a production controller for an electronics firm; Marjorie was a housewife, and the backbone of the family.

‘She was always incredibly supportive over the years,’ says Steadman. ‘I can’t tell you the number of times I phoned her up and said, “Mum, I’m really scared of this job, help me.” Opening night of a play or something. Or when I was a student, “I’m not sure if I can do this, Mum.”

‘And she was always so positive,’ Steadman continues. ‘She would say, “Never say you can’t, always say you can, and you will. You can do it.” She would never let me be negative.’

Liverpool in the 1960s – everything was in black and white until the Beatles started playing lunchtime sessions at the Cavern and the city exploded into colour. Ignoring her mother’s orders, ‘There’ll be trouble…’, Steadman would sneak off to watch them – ‘We’re just going shopping, Mum.’

She once cornered John Lennon and Paul McCartney in the post office for autographs. ‘He put, “To Alison, love Paul,” and gave it to me, then he said, “Here give it back to me a minute.” And he wrote “Beatles”, in brackets, underneath. And he said, “I thought I’d better put that, because in the future someone’s going to look at that and say, ‘Who the bloody hell’s Paul?’”

‘And then, of course, when the Beatles became famous, Mum said, “You did go there, didn’t you? What was it like?”’ She laughs.

Steadman was the family entertainer, always doing impersonations. ‘Beryl Reid and the comic actress Hylda Baker used to be on television, I adored them. Mum used to say, “There’s nothing on the television, turn it off, Alison, do Hylda Baker for us, go on.” And I’d run upstairs, get Mum’s old coat and fox fur and put a hat on, and come down and impersonate Hylda Baker.’

She does an impression now, and for all the world it’s as if Baker is at the table, pausing over the taramasalata and gigantes. ‘I was always impersonating teachers, standing in front of the class and I’d be Mrs Whateverhernamewas before she arrived, and they’d say, “She’s coming, she’s coming!” and I’d run back and sit at my desk,’ Steadman continues.

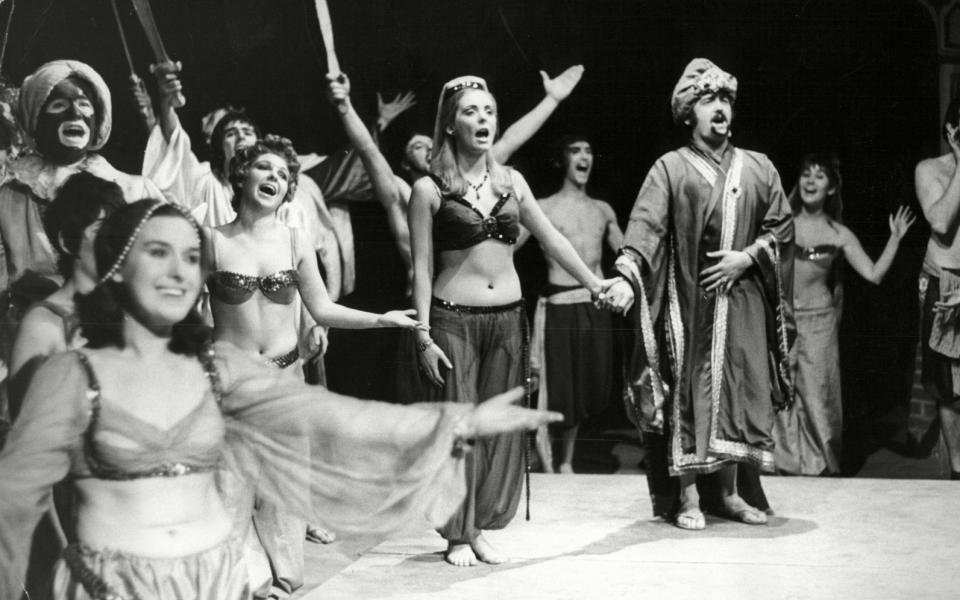

‘Entertaining and making people laugh was always a part of my life.’ It was inevitable that she’d be drawn to acting, going from school plays to the Liverpool Youth Theatre, and then at the age of 19 to the E15 Acting School in Essex – good training in the Estuarine accent for the part of Pam in Gavin & Stacey some 40 years later.

In 1973, she married the director Mike Leigh, whom she had met at E15. Theirs was a marriage that would last more than 20 years – they separated in 1995, before divorcing amicably in 2001 – and an artistic collaboration that would stretch over seven films and several plays.

It was Leigh’s 1976 play Nuts in May, about the tribulations of a couple on a camping holiday, in which she played the child-like Candice-Marie, that signalled Steadman’s arrival. This was followed by Abigail’s Party the next year, playing Beverly, one of theatre and TV’s most memorable creations; a sacred monster, funny and excruciating at the same time, whose vaulting pretensions to class and taste disguise a tangible insecurity.

‘I learned so much from Mike,’ she says. ‘He developed a unique way of working in which the characters and the narrative of a piece would be developed through a series of lengthy and painstaking improvisations – a process he once described as “discovering what the piece of work is through the journey of making it”.

‘I remember, doing Abigail’s Party; he said, “What work do you think Beverly would do?” I said, “Well she’d want to be a model and she loves make-up, so she’d probably work in one of the big stores doing make-up.”

‘So Mike phoned up and I spent the best part of the day in Selfridges watching this woman doing make-up and talking to the customers. At one point, she picked up this pale-green eyeshadow and said, “Now look at this colour everyone. I promise you that in Paris this week they’re mad for it; and whatever they love in Paris this week they’re going to love in London next week. So if I were you, I’d get this right now so you’re ahead of the game.”’

The saleswoman – a work in progress towards Steadman’s Beverly – has taken Hylda Baker’s place at the table. It’s like a private performance, I say.

She laughs. ‘Well this is my life. You just absorb all these things and then you can use them.’ Steadman’s roles over the years have made her one of those figures that the whole nation has warmed to. ‘People stop me in the street or on the Tube, whatever, and say they’ve loved a particular character,’ she says. ‘The thing I like most is occasionally people will say, “You have brought my family so much happiness,” and I love it when they say that. That is very special.’

She was awarded an OBE in 2016. Many thought she might have since joined the ranks of theatrical dames. But she demurs.

‘It’s very nice getting an OBE and I’m just sad my parents weren’t alive to see that,’ she says. ‘I’d feel a bit self-conscious if I was called a dame. But I think maybe they like theatre people, and I stopped doing theatre several years ago.’

She didn’t want to stop, but then in 2012, out of the blue, she was overtaken by the thing that every actor fears – stage fright.

She was performing in Michael Frayn’s play Here at the time – ‘a good play with lovely actors and a lovely director’ – but somehow, she says, she just couldn’t quite get on top of it. ‘And a lady that I’d known since I was 10 years old died, and it really upset me. And I think it was a combination of all these things and I found myself in a really bad place.

‘It was a classic thing that I just didn’t appreciate could happen at that age,’ she continues. ‘I was in my mid-60s. You’re just doing theatre, and loving it; you’re not thinking, one day this is going to happen. You can learn lines and everything, but suddenly you get this fear that you’re not going to be able to perform, you’re going to make a fool of yourself.’ She pauses.

‘I don’t know… It was just agony.’ She did one play after that, an adaptation of Zola’s Thérèse Raquin, in 2014. ‘It was a small role, and this woman sits in a wheelchair – she’d had a stroke, so that was handy.’ She laughs. (‘Alison Steadman’s stroke-stricken Madame Raquin,’ The Guardian wrote, ‘is terrible to behold.’)

But that was it. ‘Not being able to do theatre was a real sense of loss, because theatre was my favourite thing, without a shadow of a doubt,’ she says. ‘When you’re on top of it, and you know what you’re doing and you’ve got the audience in the palm of your hand, it’s a wonderful feeling to entertain in that way, it really is. And the thought of never doing it again made me so sad. But then I thought, come on, why torture yourself? Let it go. Do radio, do telly.’

And she hasn’t stopped. ‘I love being busy, and as long as I’ve got something coming up in the future I’m fine. But I don’t mind a gap between jobs now, because I get tired.’

Steadman has recently finished filming a second series of the BBC comedy Here We Go. ‘I loved everything about it, but my God, I was crazy with tiredness, getting up at 4.30 every morning, and not getting home until nearly at eight at night,’ she admits.

‘I’ve got to pace myself now. I can learn lines, but it takes me 10 times as long as it used to, because your brain just slows down, however much I try and keep it active.

‘I’m doing Wordle and I’m doing Spelling Bee – it makes no difference whatsoever, because your brain just goes. I’m sorry, but I’ve got thousands of lines in there and I haven’t got much room for any more.’

She doesn’t much like being 77. ‘I keep thinking, God, I’m going to be 80.’ The younger of her two sisters has died, and the elder is bed-bound now. ‘And we’ve always been such good friends; we had holidays together and would meet up, and suddenly all that’s changed,’ says Steadman. ‘And it makes me sad, to just see life…’ The thought peters into silence.

Along with a ghostwriter, she has been working on her autobiography. ‘I wasn’t going to, but I was asked out to lunch by a publisher and he really persuaded me,’ she says. ‘I said, “I’ll do it if it’s just about my childhood, my mum, my career, how I became an actress, the parts I’ve played that I’ve enjoyed. But I don’t want it to be about my marriage, my kids, my private life. I don’t want to talk about that.”’

She has two sons from her marriage to Mike Leigh, Toby, 45, and Leo, 42. She also has one grandchild, who is six years old – ‘He’s the most beautiful, adorable child on this planet, of course’ – and she will be a grandmother again in April. ‘And when I was told that news it just lifted me.’

She has been with her partner, the actor Michael Elwyn, for 28 years. ‘I love our life together. There’s a part of me, the older I get, where I’m thinking, I don’t want to be alone,’ she says. ‘I’m not a loner. Some people say, “Oh I love it. I just have a quiet time.” I don’t like it at all.’

The two of them like to go for walks, and she loves birdwatching. ‘I couldn’t live without my bird-feeders in the garden. Eating my breakfast I have my binoculars right there within arm’s reach.

‘There was a blackcap in the garden just yesterday,’ she tells me, reaching for her phone to show me a picture. But her favourites are the long-tailed tits. ‘They’re very mysterious birds,’ she explains. ‘They’re always in groups, seven or eight of them, and they feed for five minutes and then they’re gone and you don’t see them again. And I think, why don’t you come back?’

She ponders this. If she came back on this Earth and had to be a bird, she would choose to be a long-tailed tit, she says. ‘Because I’d always have company.’

Marie Curie is one of four charities supported by this year’s Telegraph Christmas Charity Appeal. The others are Go Beyond, Race Against Dementia and The RAF Benevolent Fund. To make a donation, please visit telegraph.co.uk/2023appeal or call 0151 284 1927