From alien gynaecologists to sexy snake people: the 10 craziest concept albums of all time

It is 50 years since the release of The Who’s Quadrophenia, revered as one of rock’s greatest concept albums, a grandiose masterpiece following the existential crisis of a Mod having a very bad day in Brighton. Also celebrating its 50th anniversary is Lou Reed’s Berlin, a rock opera in which a sex worker in a destructive relationship with a drug addict has her children taken away by social services and dies by suicide. A contemporaneous review in Rolling Stone magazine labelled it “a disaster” and the “last shot at a once-promising career.” Reed had the last laugh, as the belatedly acclaimed concept album eventually claimed a place in Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Albums Ever Made.

The year 1973 might have been peak “concept”, the year of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon (concept: the madness of the human condition), Yes’s Tales From Topographic Oceans (musical interpretation of mystical Indian scriptures), Rick Wakeman’s The Six Wives of Henry the VIII (Tudor history as a synthesiser opera), Jethro Tull’s A Passion Play (the spiritual journey of a recently deceased man) and two instalments of Gong’s Radio Gnome Invisible trilogy (something to do with a flying teapot and the awakening of cosmic consciousness).

It was also the year of Andrew Lloyd-Webber’s groundbreaking double album rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar, featuring Deep Purple’s Ian Gillan as the Messiah. Over in the US, teenybop pin-up band The Osmonds attempted to convert fans with The Plan, an entire album devoted to proselytising the Mormon mission. Even The Eagles were keen to signal their seriousness by describing Desperado as a concept album about outlaws and anti-heroes.

Things can get a bit blurry defining what constitutes a concept album. At its loosest, it might be considered a collection of thematically linked songs, encompassing everything from Frank Sinatra’s 1955 long player of romantic disillusion, In the Wee Small Hours, to Dolly Parton’s new rock covers album. But for most music fans, a concept album involves a work of closely defined, thematically and narratively linked songs set in an enclosed musical universe that demands to be approached in its entirety.

Having emerged with the deepening artistry of pop culture in the 1960s (with such notable if conceptually flawed examples as The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper and The Who’s Sell Out), concept albums became very associated with the progressive rock genre, flourishing in the 1970s. Yet even in our single-track streaming focussed era, the concept album remains a favoured format of many musicians wishing to signal artistic seriousness: Taylor Swift has described her latest global chart-topper, Midnights, as “a concept album … about what keeps you up at night.” Which, for a genre crammed with dystopian futures, alien invasions, messianic visitations and mental breakdowns, is pretty tame stuff.

Here, for your delectation, is a top 10 of the craziest concept albums ever. Not (I want to stress) necessarily the greatest, though all are remarkable in their own ways.

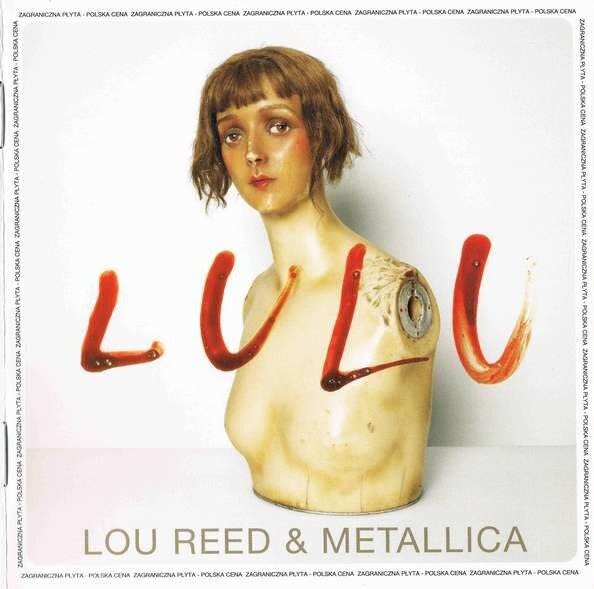

10. Lou Reed & Metallica: Lulu (2013)

The Concept: A highly sexualised female personification of desire suffers a lifetime of humiliating misogynistic horror before being murdered by Jack the Ripper. Across 95 minutes of ambient metal.

As if Berlin wasn’t quite depressing enough, for his final flourish before his death in 2013, Lou Reed recruited the heaviest band on the planet to help him make the grimmest album in pop history. Based on Frank Wedekind’s early 20th-century German Expressionist plays, Earth Spirit and Pandora’s Box, Reed intones explicitly gruesome lyrics in a dull monotone over improvised heavy metal from Metallica. It attracted some of the worst reviews of Reed’s career. “I don’t care,” the 71-year-old Reed snarled at me, during one of his final interviews. “I can’t try any harder. I can’t do any better. And my heart was pure and my soul was pure, too!” David Bowie told Reed’s widow Laurie Anderson that Lulu was his masterpiece, predicting “it will be like Berlin, it will take everyone a while to catch up.” Ten years on, the jury’s still out.

9. Genesis: The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway (1974)

Concept: A New York graffiti artist experiences a pilgrim’s progress journey through a twilight zone between life and death that involves sex with snake people and a castrated penis stolen by a raven. The hero either dies at the end or swaps his soul with his dead brother.

The sixth and final album of the first stage of Genesis’s peculiar world-conquering career is an enigmatic epic built on slippery rock, ambient noise collages, florid keyboard conflations and warped music hall. Its combination of rich melodiousness, poetic impenetrability and extravagant musical adventure have helped sustain The Lamb’s reputation as a prog classic, but even after all this time, neither listeners nor the musicians themselves seem entirely certain what it’s all supposed to represent.

Original frontman Peter Gabriel has never sounded more passionately involved than soaring and twisting through songs with baffling titles including The Chamber of 32 Doors, Silent Sorrow in Empty Boats, Cuckoo Cocoon, Hairless Heart and Here Comes the Supernatural Anaesthetist. The fantastic Hipgnosis albums sleeve included a gatefold covered in tiny text telling a convoluted tale involving such characters as the Slippermen, Lillywhite Lilith and Doktor Dyper. “I’m not sure if the story made much sense to most people, but it did mean something to me,” Gabriel later asserted. “In essence, it was about an awakening.” The subsequent shows involved Gabriel crawling out of a phallic tube in an outfit covered in inflatable genitalia, much to the disgruntlement of his baffled bandmates. Gabriel left Genesis at the end of the tour.

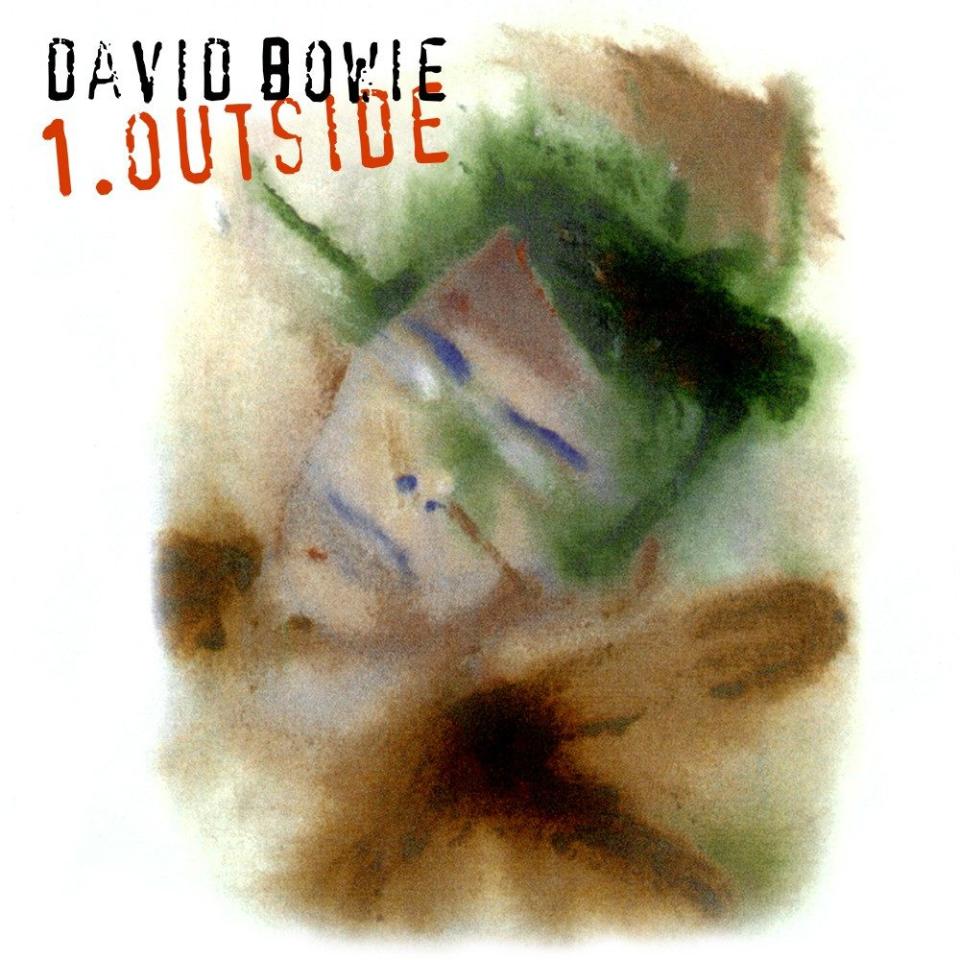

8. David Bowie: Outside (1995)

Concept: In a world where ‘Art Crimes’ are trending, a detective sets out to solve the murder of a teenager whose dismembered body has been left on display in front of the Museum of Modern Parts.

Or to give Bowie’s 20th album its full title: 1. Outside – The Diary Of Nathan Adler Or The Art-Ritual Murder Of Baby Grace Blue – A Non-Linear Gothic Drama Hyper-Cycle. Pop’s greatest stylist had dabbled with concept albums throughout his career, notably with The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars (1972) and Diamond Dogs (1974), but dived in the deep end with this mind-boggling conflation of quasi-improvised art jazz rock and fractured narrative storytelling. The tale is delivered obliquely with character songs, spoken word pieces in artificially modulated voices, segues of fake found sounds supported by music videos, an Art-Crime comic and a booklet with a short story that ends “… to be continued.” We never do find out who killed Baby Grace (although a jury convicts fall guy Leon Blank), with fan speculation favouring a theory that Detective protagonist Nathan Alder is also art serial killer The Minotaur, and all of them, of course, are alter egos for Bowie himself.

He edited the album from over 35 hours of improvisations, claiming it was the first part of an intended trilogy, and flirted with adapting it as a CD-ROM and opera. Keyboard player Mike Garson told Bowie biographer David Buckley, “There was loads of stuff that was never edited, so they have 10 albums there if they want.” Even in such an inscrutable state, Bowie’s darkest, weirdest and longest album (the full version has 33 songs and a two-and-a-half-hour running time) offers a compelling vision of art and anxiety at the end of the 20th Century.

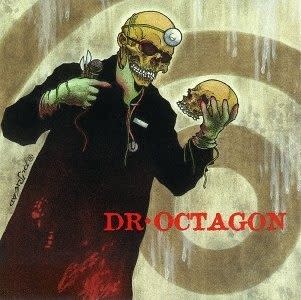

7. Dr. Octagon: Dr. Octagonecologyst (1996)

Concept: A homicidal extraterrestrial gynaecologist travels from Jupiter in the year 3000 back to Earth in 1977 to pioneer rap music.

With its narrative impulse, hip hop has been a natural home for concept albums, albeit many of the most celebrated examples (including Jay-Z: American Gangster, The Roots: Undun, Kendrick Lamar: good kid, m.A.A.d city) offer socially conscious slices of real-life drama. Rapper Keith Thornton aka Kool Keith took a rather less serious approach with this debut from occasional alter ego Dr. Octagon. Musically, it is audacious, utilising limber beats and futuristic sample psychedelia from the brilliant Daniel Nakamura aka Dan The Automator, who would go on to become a frequent collaborator with Damon Albarn’s Gorillaz.

Kool Keith weaves an absurdist, surrealist and unapologetically rude slice of afro-futurism, with Dr. Octagon’s adventures spliced with dialogue excerpts from pornographic films as he does his rounds treating chimpanzee acne and pretending to be a female gynaecologist to have sex with patients and nurses. In recent years, Thornton has reflected upon it more with embarrassment than pride, complaining that it overshadowed later more serious work. The rude humour is pretty juvenile, but the language and vision are dazzling, the influential groundbreaking sci-fi grooves expanding the palette of hip hop and warranting release in their own right on Instrumentalyst (Octagon Beats).

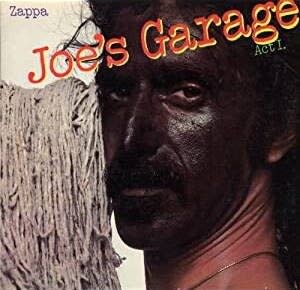

6. Frank Zappa: Joe’s Garage (1979)

Concept: Dissatisfied with his life in a garage rock band, a kid called Joe joins a religious cult promoting sexual relations with inanimate objects, winds up in prison for deviancy and descends into insanity.

A voice at the start of this sprawling three-part rock opera (originally released on two separate albums) announces it as “a special representation to show what can happen to you if you choose a career in music.” Narrated by the Central Scrutinizer of a government that disapproves of youth culture, it mixes political satire and dazzling musicianship with Frank Zappa’s penchant for scatological and entirely questionable humour. It’s not every rock opera that contains a magnum opus entitled Why Does It Hurt When I Pee, or a 9-minute electro lounge track about an orgy with mechanical appliances (Sy Borg).

It is really an excuse for Zappa to lead his virtuoso ensemble through audacious pastiches of blues, show tunes, jazz, doo-wop, lounge, orchestral, rock, pop, reggae and funk. To further complicate matters, Zappa developed a technique he called Xenochrony, which involved overdubbing unrelated guitar solos from earlier recordings. The devilishly intricate rhythm section parts on A Token of My Extreme became an object of study amongst music students. Justifying his rude proclamations in the name of artistic freedom, Zappa’s central thesis is that governments inherently treat people as the enemy, inventing laws to outlaw normal human activities. The album ends with the government criminalising music, and if you can get all the way to the end of its nearly two hours of eye-popping madness, you might conclude they were right.

5. Pink Floyd: The Wall (1979)

Concept: A jaded rock star named Pink isolates himself from society, undergoing drugged-up fascistic hallucinations on stage and attacking his fans, before finally tearing down the metaphorical walls separating him from others.

For some, it is the ultimate concept album. For others, it is the double album-length ego trip that broke up Pink Floyd. The semi-autobiographical work of bassist, lyricist and principle Floyd songwriter Roger Waters, gave him a platform to explore ideas about how trauma can be a breeding ground for political fascism. The parallels with his character Pink are evident in songs that explore guilt over the death of his father in World War II (Goodbye Blue Sky, Bring the Boys Back Home), an intense relationship with his domineering mother (Mother) and suffering at the hands of the English public school system (Another Brick In The Wall). It was inspired by a moment of self-disgust during a Floyd tour when Waters got so upset with a heckler that he spat at him, sparking a notion that “fascist feelings develop from isolation.”

What Waters has never acknowledged is the extent to which he became a domineering tyrant to his own bandmates during its fractious recording process, even sacking keyboard player Rick Wright (subsequently rehired as a session musician). Taking the concept to the full for live shows, the band built a wall during performances, bricking themselves off from the audience. “Everybody thought I was completely insane,” according to Waters, who quit Pink Floyd two years later. Aged 80, he still regularly courts controversy in live performances, recently attracting criticism for wearing his Pink fascist uniform onstage in Berlin.

4. Lol Creme / Kevin Godley: Consequences (1977)

Concept: Extreme weather conditions threaten to wipe out humanity, until an eccentric composer uses arcane knowledge of the Pyramids and numerology to write a piano concerto to counteract the forces of nature. A triple album.

Godley and Creme left hit pop-rock band 10CC to spend over a year creating this farrago of conceptual nonsense as a showcase for their guitar effects invention the Gizmotron, which could emulate orchestral instruments. Barely tying musical strands together, the great (but by then alcoholically dissolute) comic genius Peter Cook concocted a surrealist play in which he performs as all the characters, including eccentric composer Mr Blint.

Most of the action is incongruously set in a solicitor’s office during divorce negotiations whilst weird meteorological conditions manifest outside. The great jazz singer Sarah Vaughan briefly appears to sing a strange ballad of romantic farewell, while Peter Cook does silly voices.

It was released at the height of punk rock to terrible reviews and worse sales, with Kevin Godley subsequently admitting the duo had become “lost” in their ambitious studio project, locking themselves away to concoct “a semi-avant-garde orchestral triple album with a very drunk Peter Cook, while outside it was like a nuclear bomb had dropped.”

Contemporary prog maestro Steven Wilson of Porcupine Tree has frequently championed it as a lost masterpiece, although Godley is more circumspect, describing it as “a weird mix of sheer brilliance and utter sh-t. I could be wrong. It could be all brilliant and all sh-t or even all brilliant sh-t. Either way, it fried our brains for a while.” Swapping the order of their names to Godley and Creme, the duo went on to achieve success in the 1980s as synth-pop hitmakers and pioneering video directors.

3. Christine and The Queens: Redcar les adorables étoiles (prologue) (2022)

Concept: A cosmic knight falls from the stars to erotically sacrifice himself to a damsel in distress as a metaphor for gender transformation and self-acceptance. In French.

Theatrical Gallic solo artist, Héloïse Letissier, had scored a series of charming synth-pop hits as Christine and the Queens before a personal crisis of sexual identity led to him adopting the male alter ego Redcar for his third album. Composed in a two-week burst of frenzied activity, Letissier’s electro-operatic fantasy of cosmic transformation is delivered with grand gothic intensity, vocals pouring forth over electro-funk grooves, fizzing synths, crashing drums and squalls of electric guitar. Combien de Temps runs to over eight minutes, with tirades about how “from my songs I make oaths / From the magic doors towards comprehension / But my sun is my light / The melody is the primal ocean …” There is something about a stunned Sir Lancelot, and a French pun linking a boat and a penis.

It is a lot to take in, and following two hit albums, Redcar bombed in the charts. Letissier, however, was not to be discouraged, continuing the story of angelic visitations with English language follow-up Paranoia, Angels and True Love this year. It featured Madonna guesting as an omniscient being known as Big Eye, given to spoken word pronouncements such as “This is the voice of the big simulation, the terrestrial fruit is of no importance now.” The exact meaning of all of this remains largely inscrutable to anyone but the artist himself, who explained it during a series of extraordinary live shows as “a ritual alchemisation” of “the spirit, the soul and the flesh” resulting in a merger of “love and imagination, transmutation, reinvention that leads to revolution.” Peter Gabriel might empathise.

2. Parliament: Funkentelechy vs. the Placebo Syndrome (1977)

Concept: Funky aliens have a dance-off with a music-hating villain to keep Earth safe for dancing.

As conceptualised by Aristotle, “entelechy” is the condition of a thing whose essence is fully realised. In the cosmic visions of psychedelic funk pioneer George Clinton, funkentelechy is the full realisation of humanity’s innate funkiness in the face of distractions from lesser forms of dance music such as the weakened placebo of disco (Clinton was not a fan). With his two great ensembles, Parliament and Funkadelic, Clinton stands alongside James Brown and Sly Stone as a funk innovator, bringing surreal humour and outlandish afro-futurism to the genre.

Indeed, to fully appreciate the concept of Clinton’s space funk opera, you might need to bone up on Parliament’s previous two releases. Mothership Connection (1975) introduces Clinton’s intergalactic alter ego Starchild, a space-age standard bearer for freedom in a world of repression. The Clones of Dr. Funkenstein (1976) advances the sci-fi plot by revealing that the secret of funk was brought to earth from outer space thousands of years ago and hidden in the pyramids until people were ready to receive its groovy blessings. Cosmic funkmaster Dr. Funkenstein sends his clones to, at last, fulfil this funky prophecy. On Funkentelechy vs. the Placebo Syndrome, Starchild does battle with anti-groover Sir Nose D’Voidoffunk, whose villainy is defined by his pride in his inability to dance. Armed with Dr. Funkenstein’s Bop Gun, the funky aliens persuade Sir Nose of the error of his ways and win the cosmic dance-off for all mankind. Phew.

If that’s too much to take in, you can, thankfully, ignore all the nonsense and just dance to one of the funkiest, squelchiest, most joyous albums ever made.

1. The Who: Tommy (1969)

Concept: Traumatised, bullied and sexually abused, a deaf, dumb and blind boy becomes a pinball champion through a heightened sense of vibration, achieving messiah-like status when he recovers his senses.

The original rock opera is still just about the craziest concept any band has crafted a masterpiece from. Guitarist, songwriter and band leader Pete Townshend had already coined the term “rock opera” for shorter linked suites of music on previous Who albums A Quick One and The Who Sell Out. For Tommy, he came up with a double album’s worth of songs following a complex narrative complete with overture (with some contributions from bandmates John Entwistle and Keith Moon). The result was a sensation, remaining in the charts for two years and eventually selling over 20 million copies, with Life magazine hailing Tommy as “a full-length pop opera that for sheer power, invention and brilliance of performance outstrips anything that has come out of a rock recording studio.”

The Who’s live performances of Tommy remain legendary and are arguably even better than the official album, exuding a fierce heavy rock power that the elaborate studio recordings sometimes lack. Tommy has subsequently been adapted as a ballet, opera, symphony, Broadway Musical and blockbuster smash 1975 Ken Russell film starring Who frontman Roger Daltrey, with Tina Turner as the Acid Queen and Elton John performing Pinball Wizard back by The Who. “It really does show how flexible rock and roll is, and what a lot of bullsh-t is talked about what it can and can’t do,” Townshend proudly told Rolling Stone in 1969. The equally extraordinary Quadrophenia would follow four years later.