Albert Finney remembered: The working-class hero who inhabited every role he played

Albert Finney was the actor’s actor. Curiously, he never quite became the household name that his talent and string of theatre and film successes should have ensured. But he had a magnetic stage presence and a startling versatility on screen that few could emulate.

It was on stage that he first burst on to the public consciousness, and in a rather strange way. He was understudying Laurence Olivier in Coriolanus at Stratford in the late 1950s, and his performance became the talk of the industry.

Finney later recalled the moment with characteristic, caustic wit, and at the same time gave an insight into what was to become a recurring story of wondrous understudy performances.

There was a “groan round the auditorium,” he recalled, “when Olivier’s absence was announced.” But then the audience were rather impressed that you “had the costume on and weren’t in flannels” and you knew the lines, and ended up giving you a standing ovation.

Many a standing ovations followed. Though the role of Billy Liar became associated with Tom Courtenay because of the film, it was Finney who had created the part of the brooding, fantasising Walter Mitty – the notherner of the West End in 1960. Many other performances became etched on the theatregoers’ collective memory. One such was in fairly recent times, when he starred in the first performances of Yasmina Reza’s ART, alongside Courtenay and Ken Stott. Finney’s turn as the man bewildered and frustrated that his best friend could buy and love a painting which was just a white canvas, was wonderfully comic. But underlying it, he showed the more tragic frustration of a man aching to connect with a male friend and not having the words to do so.

Finney would always dominate the stage. It was no surprise that Olivier was among his biggest fans, but he was never really one for the chat show or interview circuit, and his real persona was largely unknown to the public.

As is the case when great stage actors die, it is for their movies that they are publicly lauded and remembered. But in Finney’s case, the roll call of memorable screen performances over 60 years, with five Academy Award nominations, is such as to justify this. Some of them were cult favourites, like the sixties vehicle Two for the Road with Audrey Hepburn.

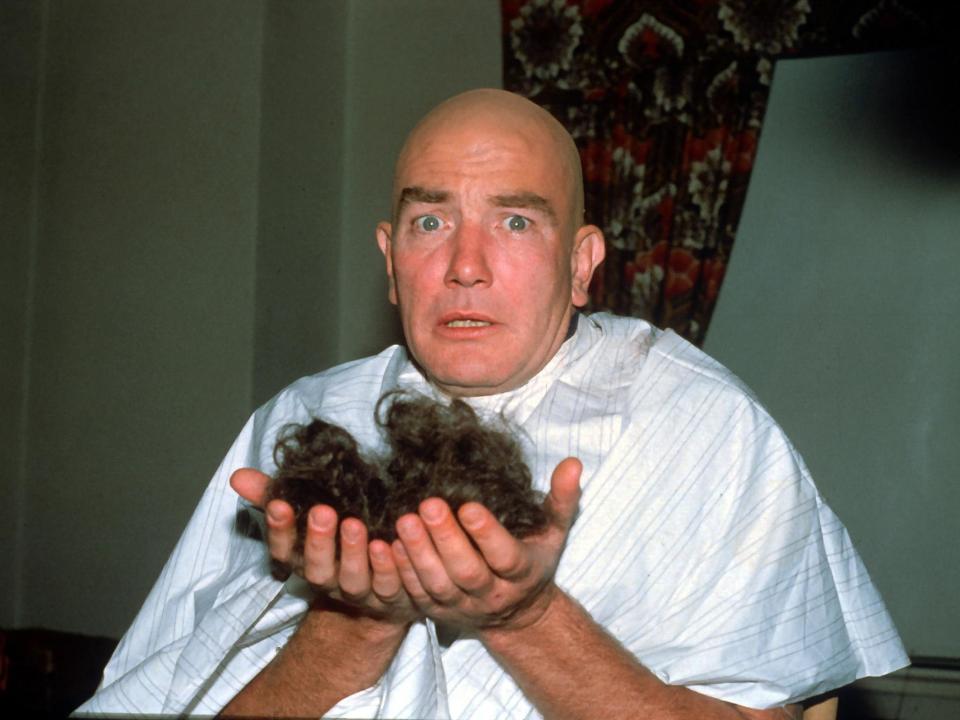

A wider public knew him for Murder on the Orient Express, where his Hercule Poirot had a meticulousness and narcissism, which was closer to Agatha Christie’s original than any of the ones that followed. And, of course, generations of children and their parents will remember his imposing, pompous billionaire Daddy Warbucks in Annie, struggling to admit to himself how the orphan girl had captivated him. Finney excelled in conveying that yearning that could not be put into words.

Well before that, though, Finney had epitomised, arguably invented, the working-class hero, or more accurately anti-hero on screen – in Tony Richardson’s version of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. He effectively, alongside Courtenay, led the new wave of working-class actors changing the face of British film and TV. It was for a very different role, in 1963, the flamboyant Tom Jones of the Fielding novel, also for director Tony Richardson, which earned Finney his first Oscar nomination.

Latterly, he appeared in the Bond film Skyfall, and the Bourne movies. Finney, who almost certainly turned down a knighthood, never attended an Oscars ceremony, saying: “It seems a long way to go just to sit in a non-drinking, non-smoking environment…Walking around in the spotlight having to be me is not something I’m particularly comfortable with or desire. I’d sooner pretend to be someone else.”

That gives a clue as to why the public never really felt they knew the man as opposed to the actor. But from that young Billy Liar on stage, through movie roles such as Scrooge and lawyer Ed Masry, opposite Julia Roberts in Erin Brockovich, to the Emmy-winning 2002 portrayal of Churchill in TV’s The Gathering Storm, few will not have seen an Albert Finney performance. And all who saw him will have marvelled at how the one-time working class hero quite simply inhabited every role he played, and managed in understated performance to convey momentous, inner feeling.