Ain’t Too Proud at the Prince Edward Theatre review: Temptations musical rolls out hit after Motown hit

Hit after peerless Motown hit rolls out in this slick, well-drilled, jukebox musical from Broadway, about the “number one group in the history of rhythm and blues”, The Temptations.

It’s basically two-plus hours of Sixties and Seventies bangers – My Girl, Shout, Just My Imagination, Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone – performed to fiercely demanding choreography, and loosely strung on a sleevenotes-style history of the group’s personal and professional ups and downs. And it’s none the worse for that. Never mind the narrative; just listen to that back catalogue.

Des McAnuff’s high-energy production is based on the memoir co-written by the group’s motivating force and sole surviving original member, Otis Williams, so it’s a necessarily partial account.

Otis, in the person of the commanding Sifiso Mazibuko, tells us how he formed the group on the mean streets of Detroit in 1961 and held it together as egotism, substance abuse and illness gradually laid waste to the brotherhood of the initial five-strong lineup.

The rapid turnover in bands can look hilarious when skimmed over in shows like this, but it’s managed here with more dignity than in, say, The Drifters Girl. Both groups are still going, but the Temptations are only on their 27th member while the Drifters have gone through at least 60.

Though this is an undemanding, relatively sanitised piece of work, we get a hint of the ruthlessness of the Motown machine when boss Berry Gordy relieves Smokey Robinson of writing duties for “the Temps” in favour of the funkier Norman Whitfield. And he takes Whitfield’s storming Vietnam anthem War off them because it’s “too political” for a group achieving crossover with white audiences. The group’s hit Cloud Nine is accompanied by Williams’s discovery that all of the rest of the band are freebasing cocaine together shortly before a major gig.

The social context of the times is succinctly sketched in: the group are shot at and racially abused in the South, and it’s a huge deal when they get on network television. On the personal front, a few scenes throw light on the havoc that constant recording and touring wrought on Williams’ family life. The romantic entanglements of the others are pretty much dispatched during a single number, Since I Lost My Baby.

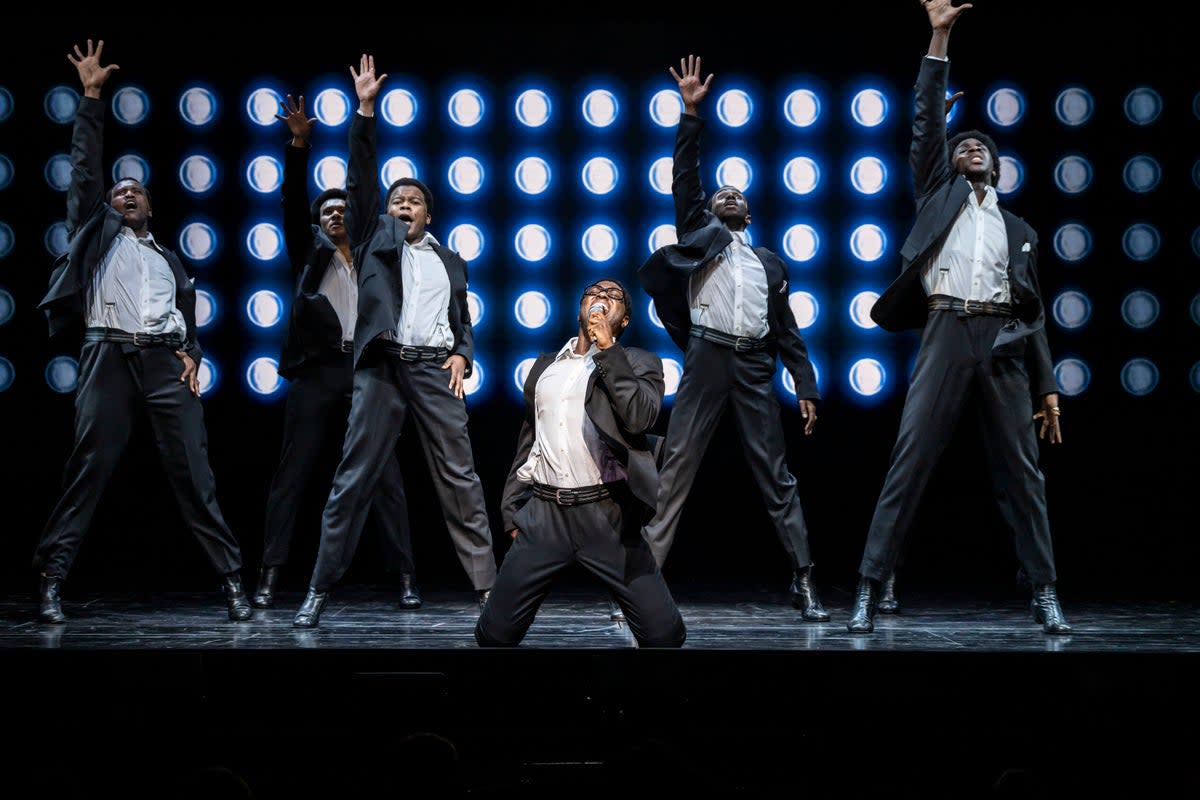

Choreographer Sergio Trujillo’s ruthlessly demanding choreography has the cast jinking like a drill troupe, twirling like gymnasts and at times undulating like boneless anemones. The design consists largely of back-projected tour-date locations and landmark newspaper headlines (the Detroit riots, Martin Luther King’s murder), with props and people wheeled on as necessary.

But this show is really about the performances of those timeless songs. There isn’t a duff voice on stage, but Tosh Wanogho-Maud and Mitchell Zhangazha deliver particularly charismatic, powerhouse turns as lead vocalists David Ruffin and Eddie Kendricks.

Cameron Bernard Jones uses his deep bass tones to great comic and musical effect as Otis’s first friend and recruit, Melvin. After frenetically alternating anguished, stage-front narrative with background hoofing and harmonising, Mazibuko’s Williams finally gets a solo on a valedictory What Becomes of the Broken Hearted. The departures of his four “brothers” are surprisingly moving.

Compilation musicals have had a bad press, recently and historically. This one is a hugely superior example of the genre.

Prince Edward Theatre. booking to October 1; buy tickets here