Adoption, witchcraft and Britain’s most hated woman: The ‘cash for babies’ mum 21 years on

A 2,000-mile dash across the United States. A hasty, legally questionable adoption in Arkansas. A British woman accused of performing dark magic. An intervention from Tony Blair. The story of “the internet twins” – perhaps better known as the “cash for babies” scandal – had so many bizarre twists and turns, and such an extensive cast of eccentric characters, it could fill not just a tabloid but an entire newspaper stand. In January 2001, after The Sun broke the story of how a couple from Buckley in north Wales had paid £8,200 to adopt nine-month-old mixed-race twins over the internet… well, it basically did. Journalists couldn’t get enough of the story, especially when it emerged that a different couple – this one from the US – had also paid thousands to adopt the very same girls. Within weeks, both couples and the twins’ birth mother were all vying for their custody.

As journalists, politicians, social workers and police all leapt on the story, it split and refracted. From one angle it appeared to be about the dark potential of new technology – the overseas adoption of “the net babies” seeming to confirm fears that the nascent internet was a corrupt and lawless zone, where everything had a price. From another angle, it was a tale as old as time: greed, manipulation, the trafficking of society’s most vulnerable. But what if both of these angles weren’t quite right? What if the truth was a bit less sensational… if equally messy?

It is more than 20 years since the twins first arrived in the UK and, a few months later, returned to the United States in the care of a third – and final – adoptive family. The idea of wading through all of the story’s headlines, chat show appearances and court records seems like an almost insurmountable task. Which is perhaps partly why, in Prime Video’s new documentary series Three Mothers, Two Babies and a Scandal, the story is told three times over and from different perspectives.

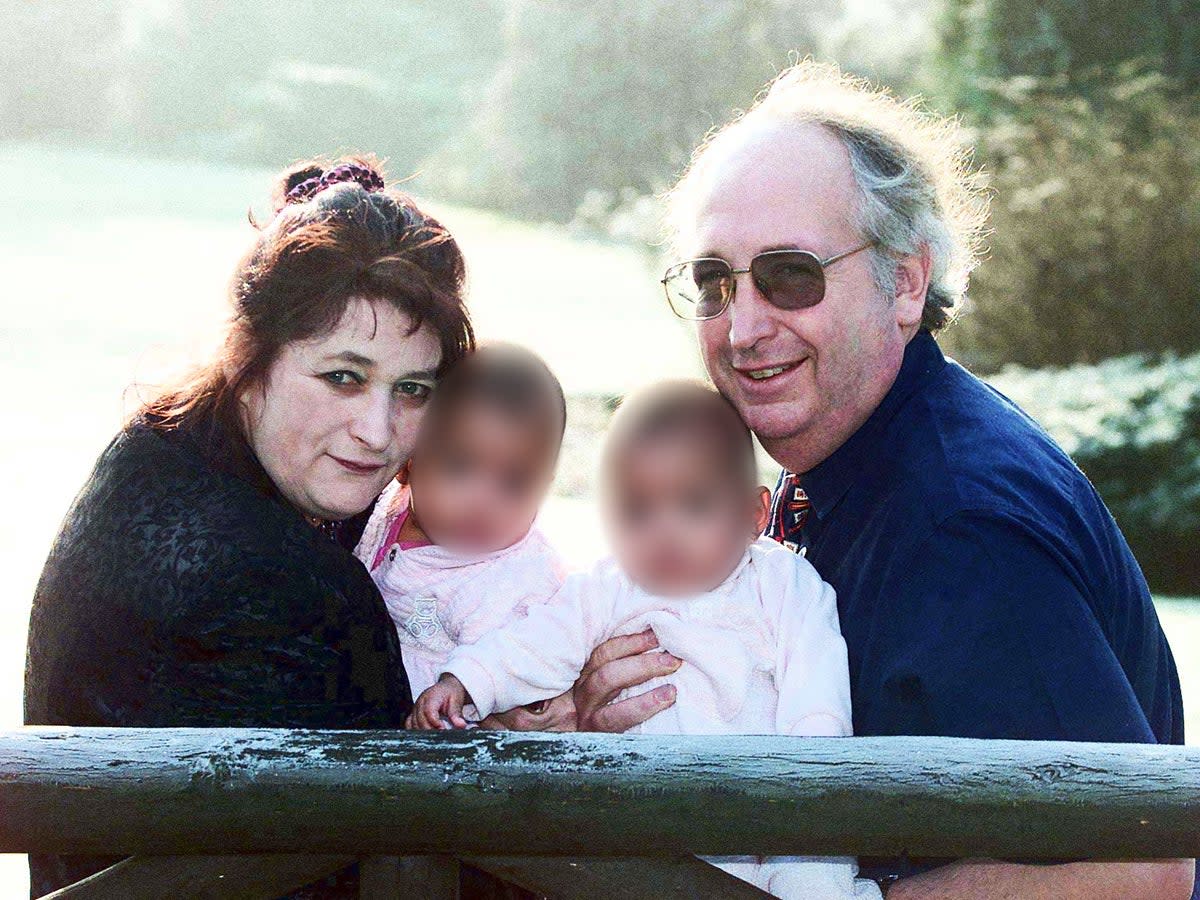

We hear from the twins’ biological mother Tranda Wecker, who put the children up for adoption through a sketchy online agency. We hear from Californian Vickie Allen, who – via the agency – paid roughly £4,000 for the twins. We also hear from Judith Kilshaw, the Welsh woman who – with her husband Alan – “bought” the twins from Tranda, who’d taken them back from the Allens two months after the first adoption had gone through. She had told Vickie and her husband Richard that she was taking them away for a weekend visit, when truthfully she was handing them over to the Kilshaws. At its heart, the aim of this three-parter seems to be to return these women – the “three mothers” of the title – their voices.

But because, as an American journalist declared at the time, “this case involves deceit, abduction, the internet” and cold hard cash, the narrative also skips and loops around like a tumultuous rollercoaster. Each woman’s respective narrative collides with and challenges the others. It means the series isn’t a straightening out of the story but more of a zigzag. The only definitive truth might be that there isn’t one – that Judith nor Vickie nor Tranda is totally right or wrong. Early on in the show’s first episode, an FBI agent involved in the case sums it up pretty deftly: “It was a soup sandwich from the beginning – there was a big sloppy mess.”

Another person who sums it up quite well is none other than Judith Kilshaw herself. “The more you tried to put it right, the worse it went,” she tells me down the phone from her home in Wrexham. Such clarity might surprise anyone who followed the “cash for babies” scandal at the time. In parliament, Tony Blair declared the “sale” of the babies “disgusting”, and the Kilshaws eventually declared bankruptcy. Judith was even labelled by one newspaper as “the most hated woman in Britain”.

When I speak with her a few days before the release of the docuseries, Judith has a nasty cough and is in the middle of getting a heat pump installed at her house. It means she sometimes has to leap up mid-sentence to let people in and out, ask about the work being done, and pull her pets away from the door. But this hubbub is both endearing and, it has to be said, entirely expected. When the Kilshaws adopted the twins back in 2000, they had four dogs, four cats, a couple of horses, and a pig called Philip – he was often encouraged by Judith to do tricks for visiting journalists. This menagerie of animals was just one of the reasons why, of the “three mothers” in this tale, Judith was selected for particular derision in the tabloid press. It also had something to do with how she smoked, how she spoke and how she dressed. Judith swore at the press, cracked jokes, demanded vengeance, and once arrived at the High Court wearing a necklace that spelled out “Foxy”. According to some tabloids, Judith was also a witch who used voodoo dolls and “the hardest forms of black magic” to get the twins back.

With an apparent instinct for making a bad situation worse, the more media appearances and interviews the Kilshaws gave, the more their credibility was eroded. Yet, to Judith, this was a result of the aggressive tabloid culture of the time. “The journalists’ behaviour was appalling,” she says today. Speaking about the “manic” four days after The Sun’s exclusive went to print – when the Kilshaws holed up in Mold’s Beaufort Park Hotel to both address and fend off the press, the police and social services – Judith says she witnessed reporters “fighting each other, trying to get in to get the story”. She is adamant: “I think it showed the very worst of journalism.” Yet she also openly admits that she would “stand there and give as good as I got with them lot – no paper owns me”.

In the docuseries, old footage shows Judith being chased out of court and into a car by a crowd of paparazzi. Hordes of cameras push through the open door and into the backseat. The car starts moving and Judith keeps the door wide open, letting the metal thwack against a row of expensive lenses. It’s hard not to think of Britney Spears a few years later, her head freshly shaved, attacking a paparazzi’s car with an umbrella. But it’s also hard not to think that, from the very start, Judith Kilshaw’s attitude was akin to flinging a red rag at a raging bull. Is that victim blaming? Or does her curious mix of belligerence and naivety prevent her from seeing herself as anything but a victim?

Judith is undeniably eccentric, in a way that could certainly be read as defiant and impudent. At one point in our conversation, she launches into an unexpected and fairly long story about getting into a series of scraps with an attendant at her local supermarket over carrier bags. The anecdote culminates in Judith telling the cashier she’s going to “stick [the bag] up my ass – and if you keep hassling me, I’m gonna stick it up your ass”. What this belies, though, is the cheeky and anarchic humour with which she tells stories – the exaggerations and embellishments she sprinkles through our conversation, and the way she mocks herself. She describes one incident as “a right put-your-foot-in-it”.

If I was someone rich, wealthy, or of stature, they wouldn’t have been able to write what they wrote

Despite her experiences with the press, Judith still has an open, devil-may-care attitude, and an innate appreciation for the absurd. It is clear to see how the media of the early Noughties spun this careering bluster into something far stranger than it actually is. But I can also sense a vulnerability in Judith that wasn’t allowed to emerge 20 years ago. “[The press] will find a weak link,” she says, “and if they find a weak link, they’ll go for the kill. And I was the weak link.” The Kilshaws were accused on all sides of being attention seekers, but, listening to Judith now, it is abundantly clear they didn’t relish their position in the limelight. They just made the lethal error of believing they might be able to have some control over the narrative. That they could, in Judith’s words, “put it right”.

“I found it very depressing in a way,” she says. “If I was someone rich, wealthy, or of stature, they wouldn’t have been able to write what they wrote. But once they realise that you can’t sue them or you haven’t got the funds, they write what they want.”

It’s impossible not to have empathy for her. At the same time, here she is, in this documentary, diving back into media attention. How does she feel going back to the story two decades on? “OK, really,” she says. “I think if it sets a record straight…” Although she now seems more aware of this perhaps not being possible, saying the docuseries “can’t set it totally straight”. Later, she admits she thinks it won’t change the narrative that exists around her. “It’s a bit like Matt Hancock,” Judith says in a typical conversational leap – one that starts to make sense if you decide to stick with it. “People have perspectives of what they think of him – he’s gone and he’s faced all the trials [and] maybe it’s going to change some people’s minds.” A similar “maybe” hangs over the documentary, too. “There’s a chance to change minds, but it’s not definite, is it?”

If minds aren’t wholly changed, it might be because Three Women, Two Babies and a Scandal remains a partial retelling. There are three women who don’t have a voice in this – notably the woman arguably the most culpable for the chaos that ensued. She is Tina Johnson, dubbed “the baby broker” for running the online adoption agency that first solicited fees from the Allens, the Kilshaws and many others. Having declined to comment, she is only shown in glimpses.

When I ask Judith how she feels about Tina Johnson having been relatively absent from the series, she is typically wilful. “I thought: if she’d got spunk about her, she should have stood up and been counted and said, ‘I run this agency. Yes, I was in charge of this, and this is how it worked, and this is where I run my office from’,” she says. “But no, she went to ground.” To Judith, this proved that Johnson “hasn’t got the courage of her convictions”.

Yet the biggest absence from the story is not Tina Johnson but the twins themselves. Now in their early twenties and living and studying in the US under different names, the two girls at the centre of this storm remain silent and at a remove. Neither the viewer, nor their “three mothers”, ever hear from them. But ultimately, perhaps it is this resolute quiet in the face of such clamour that is the most powerful statement of all.

‘Three Mothers, Two Babies and a Scandal’ is streaming on Prime Video now