‘At 77, I am becoming who I am’: Henry Winkler on the Fonz, fans, and finding self-esteem

Henry Winkler hadn’t clocked how famous he was until he asked for his fanmail to be sent to his apartment. It was 1974, he was 28 and had landed a gift of a role in Happy Days, a sitcom about a preppy midwestern teenager and his friends and family. As the strutting high-school dropout Arthur Fonzarelli, AKA the Fonz, AKA Fonzie, Winkler was meant to be a peripheral character, though he was an instant hit with audiences – so much so that producers wanted to change the title to Fonzie’s Happy Days (Winkler begged them not to). When the fan letters arrived, there were 50,000 of them.

“Box after box, and I read them all,” he says. “Some of them were just a sentence in crayon, others were so dear and thoughtful. And get this: I pulled out one and it said” – he adopts a comedy German accent – “‘I sink zat Fonzie eez very good and ABC should give him more to do on ze show.’ I looked at it and thought: ‘I know that handwriting. That’s my fucking mother.’”

Winkler, 77, is talking from his study at home in Los Angeles. As we chat, his two dogs wander in and Winkler calls them over to introduce them. “Dogs rule my heart,” he sighs, happily. “I miss them when we travel, I love them, I kiss them goodnight.” Once, his wife, Stacey, found a stray puppy and, after no one claimed him at the shelter, adopted him. What they thought was a labrador grew into a great dane. “At night he slept on top of you so you couldn’t get up to pee unless he said ‘OK’,” Winkler says.

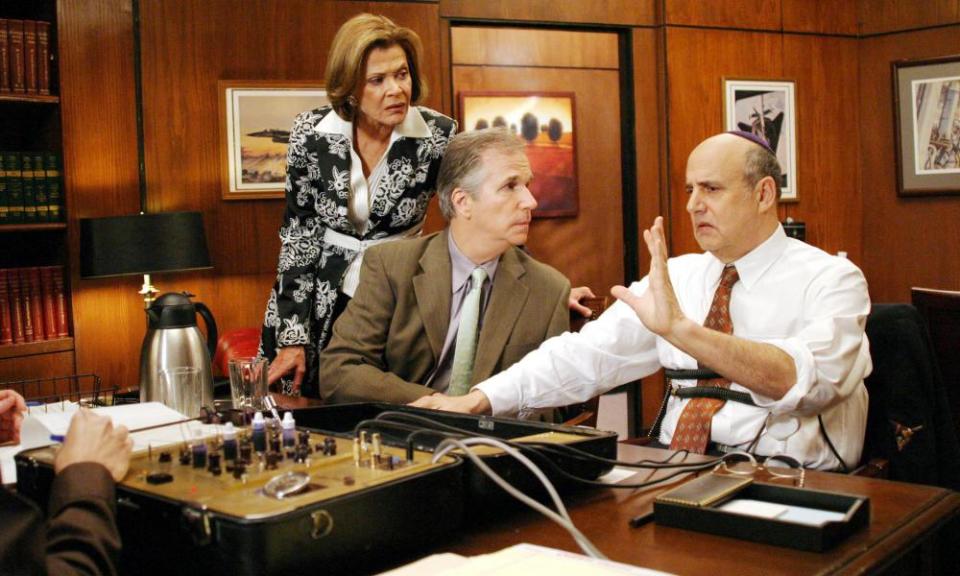

After 10 years playing the Fonz, Winkler branched out. He was offered the part of Danny Zuko in Grease but turned it down, moving into producing, directing and, in the early 2000s, co-writing children’s books. This was out of necessity since the acting roles had all but dried up. Then, in his late-50s, he was cast as the incompetent attorney Barry Zuckerkorn in Arrested Development. There was a Happy Days connection: the series was made by his co-star Ron Howard’s production company and he also did the voiceover. Booked for one episode, Winkler ended up staying for five years. After that came stints in Parks and Recreation and, in 2018, HBO’s beloved black comedy Barry, for which he won an Emmy.

But it is Fonzie that people want to hear about. When I ask Winkler if he is sick of talking about him, he shakes his head and gestures to his surroundings. “Look at this beautiful room,” he says. “If this computer weren’t so big, I would show you my new backyard with my fake grass. It looks like Mar-a-Lago. I have done everything I’ve been able to do because of Fonzie.”

We are here to discuss his latest project, a memoir called Being Henry, which he was persuaded to write by his son, Max, a TV writer and director. Given Winkler has severe dyslexia, he initially dismissed the idea. “I said: ‘Look, I write children’s books. I never thought I could do that. But a memoir? There’s no way I can do that.’” But Winkler mentioned it to his agent, who made some calls and then came back with an offer too good to refuse. So Winkler teamed up with a ghost writer, James Kaplan, and crafted an entertaining, candid and open-hearted account of his life and career.

We learn of his early years as the youngest child of German-Jewish parents. In 1939 his father, Harry, who ran a lumber business, had tricked his mother, Ilse, into leaving Berlin by telling her he had to go to the US for business. Their relatives, who insisted on staying behind, were all murdered by the Nazis, though Ilse still couldn’t forgive her husband for his deception. As a child, Winkler struggled with learning, leading his parents to nickname him “dummer hund”, or dumb dog. He recalls being left alone in their Manhattan apartment in his early teens at the weekends and instructed to study. On their return, his father would lay his hand on the top of the TV to see if it was warm: “It was more important that he punish me if he felt the warmth of the top of the television than it was to help me because I wasn’t understanding what I was learning.”

Harry hoped his son would take over the lumber business, but Winkler had other plans. He loved acting, something he attributes to never feeling seen or heard by his parents. On finishing school, he studied theatre at Emerson College and at Yale School of Drama. He struggled to learn lines, for which he was roundly mocked, but he was undeterred. “I live by two words,” Winkler states. “Tenacity and gratitude. I was extremely single-minded.”

After college, Winkler worked in theatre in New York, keeping himself afloat with occasional TV commercials. After several years living job to job, he was offered some advice by his agent: “He told me: ‘If you want to be known in New York, stay here. If you want to be known to the world, go to California.’” So Winkler packed his bags and moved to Los Angeles. Within a matter of weeks, he got his first TV job playing a charismatic greaser called Fonzie.

Winkler adored Happy Days, although, as he reveals in Being Henry, he was dogged by low self-esteem. He never bought into the Fonzie hype as “I never believed what everyone was saying about me. I was the guy who had failed geometry four times, the dumb dog, so it just didn’t make sense.” When he was 31, he was finally diagnosed with dyslexia, which came as a relief but it also left him bitter and angry. “Yes, I had something with a name. But all that time I had been put down, yelled at and made to feel less than, for something that was genetic. Dyslexia diminishes your self-image. People tell you you’re stupid and you believe it.”

When Happy Days came to an end in 1984, Winkler was adrift. “I had no idea what to do next. By now I was married [he and Stacey had met in a clothes store in 1976] and had three children but I couldn’t get hired. My brain hurt, I was in psychic pain.” It was at this point that his lawyer, Skip Brittenham, took him fishing and suggested they start a production company.

And so Winkler embarked on a new career as an executive at Fair Dinkum Productions. The first show he sold was MacGyver, the name of which became a byword for the act of improvising a solution to a problem. (It wasn’t the first series connected to Winkler that would coin a phrase; Happy Days yielded “jump the shark”, to describe the point at which a good show tips into silliness.) In 1993, he directed the film Cop and a Half, starring Burt Reynolds, who behaved atrociously. Asked to repeat a line, Reynolds threw a bottle at Winkler’s head. “Burt,” he said calmly, “I’ve never been so happy to be this short in my life.” Reynolds nicknamed him Thumper, after the rabbit in Bambi, because he couldn’t make him angry. Winkler gave directing a miss after that.

While Winkler carried on developing shows throughout the 1990s, he knew his heart lay in acting. There were times when he would spend all day waiting for the phone to ring. “I would call my agents and say, ‘Nothing?’, and they would say, ‘Nothing’, and I would be this ball of fear and sadness. But now I’m so grateful. I have great representation right now from people who are 40 years younger than me but who are strong and wise.”

Winkler’s delight at his recent run of work is palpable. Discussing Barry, in which he played Gene Cousineau, the acting coach who becomes the eponymous hitman’s mentor, he exclaims, “I mourn that that show is over. I remember the first reading. The head of HBO was at one end of the table and I’m sitting next to Sarah Goldberg, who plays this aspiring actor Sally, who I had to berate. So I yelled, ‘Bullshit! You just make me nauseous’ and I slapped that table, and the man at the end of the table jumped. Afterwards everyone said: ‘I had no idea that was in Henry Winkler.’”

Seven years ago, Winkler also embarked on a course of therapy, which he says finally helped him locate the confidence that was bullied out of him as a child. Writing his memoir has further helped him to lift the fog and live “in the here and now. You never stop learning. What I have realised is that when I was younger, I was who I thought I should be. Now, at 77, I am becoming who I am.”

Being Henry is published on 31 October by Macmillan.

This article was amended on 13 October 2023 to correct one of Henry Winkler’s quotes.