Question 7 by Richard Flanagan review – this deeply moving book is his finest work

Reading Question 7 in the aftermath of recent news, from the referendum failure to enshrine an Indigenous voice in the Australian constitution, during the days that have followed Hamas’ brutal attack on an Israeli kibbutz one soft Saturday morning, to the declaration of war, again, the scale of human suffering eclipsing all reason – I felt an immense sense of clarity. Clarity might not be the right sentiment, perhaps it’s a lightness, a levitation as witness – I cannot quite place it, but as Question 7 exposes so astonishingly, words are faulty things.

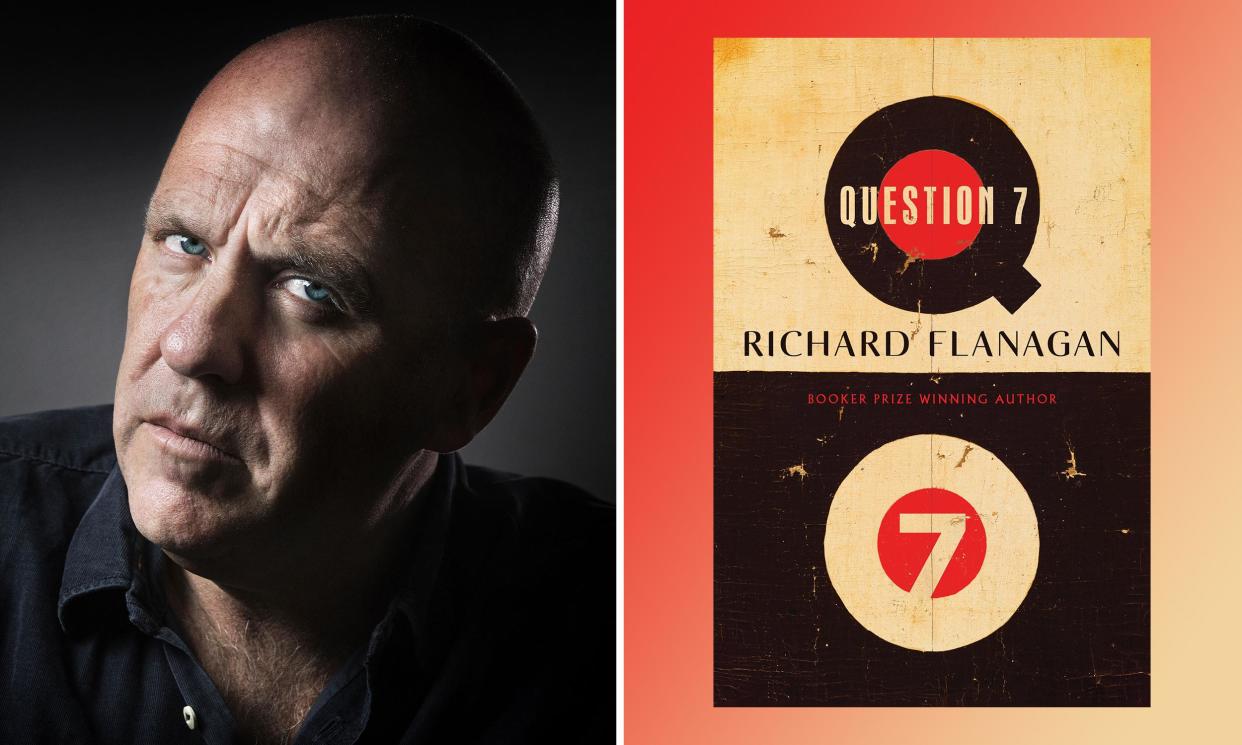

Booker prize winner Richard Flanagan’s 12th book stands alone in its structure and its thread of thought as it bisects his oeuvre between the fictive and the factual. It is a brilliant meditation on the past of one man and the history that coalesced in his existence. Judgment befalls Flanagan again and again, and by his own pen, the irrefutable details of his birth and eventual death are writ large in a shame that he wrestles with as if meeting some beast; or, like the sentiment from Rebecca West to HG Wells – their tumultuous affair plays a pivotal role on these pages – some “beautiful voice singing out of a darkened room into which one gropes and finds nothing”.

Only the best writing is so affecting that a reader has a physical reaction

Flanagan explores old, razed and sacred ground that he’s visited before in his writings – the prisoners of war and the Japanese death railway, white Australia’s Black history, the convict and settler bloodlines of fertile Tasmanian country, and the cold rapids of the mighty Franklin River. But here everything that has ever burnt the author becomes an elixir, a balm for everything that happened before he was born, and as he illustrates, will happen long after he, and we, are gone.

The butterfly effect of history culminates in either Flanagan’s father’s early death as a PoW in Japan, Flanagan having never been born and this book having never been written; or the atom bomb dropping on Hiroshima, his father living, and Flanagan alive and writing. The words here all collide at the same destination – that is, the question from which the book takes its title: Question 7, Anton Chekhov’s parody of a school test problem:

Wednesday, June 17, 1881, a train had to leave station A at 3 am in order to reach station B at 11pm; just as the train was about to depart, however, an order came that the train had to reach station B by 7pm. Who loves longer, a man or a woman?

Trying to summarise the title, and how it rests in this wonderful book is a futile act, akin to describing a certain middle note in a perfume, but the question lingers, as does the enduring nature of love and who it belongs to. When the author visits the site where his late father was tortured, the Ohama coalmine in Japan, he finds “no memorial, no sign, no evidence” at the site but rather a love hotel. “What remained, or rather what existed, was only the oblivion of pleasure in another’s arms – the same oblivion that simultaneously prefigures and denies death. As if the need to forget is as strong as the need to remember. Perhaps stronger,” Flanagan writes. “And after oblivion? We return to the stories we call our memories, perplexed, strangers to the ongoing invention that is our life.”

Related: Richard Flanagan: ‘I still feel it shameful to not finish a book, even a bad one’

Frank Sinatra’s song That’s Life played in my mind for days after reading Question 7, Flanagan using those two words as a break in the horror, an antidote to the question itself, a sort of clasping of hands, a prostration at the past, and the hell on earth and the pain in one’s heart. While reading I found myself abruptly shutting the book again and again, and steadying my own heart with a hand at my throat. Only the best writing is so affecting that a reader has a physical reaction; beyond the laughter and the tears and the sighs, Flanagan wants to know what he doesn’t want to know about himself and in that process of uncovering, I was deeply moved.

It was only recently I read a passage online and memorised, for which I cannot find the source: “We all long to write the poem that will stop the deaths.” Here I suspect was Flanagan’s intention – to stop the deaths that play on his mind, of the residents of Hiroshima below the atom bomb on another soft morning, to stop his own death below the powerful river rapids 40 years ago, to stop the genocide of Tasmanian Aboriginal people at the hands of the Martians of Wells’ imagination, that landed not in Woking, Surrey, but on the Tasman shore.

Question 7 is Flanagan’s finest book. It is a treatise on the immeasurability of life, reminiscent of the Japanese tradition of mono no aware, the psychological and philosophical sweep of Tolstoy, and enmeshed in a personal essay that is tuned as finely as WG Sebald’s Rings of Saturn. In the meditative, circular story structure of memoir and history and auto-fiction, replete with nuance and sound thought, Flanagan doesn’t just present Chekhov’s Question 7 – appearing as a thread, he doesn’t just pull at it but unravels an entire tapestry. He travels to the metaphorical weaver, the shearer, the shepherd, and the hooved animal itself – and reaches into the deepest past where, he is so astute in writing, “there is no memory without shame”.

Reading Question 7 made me think of the Sufi poet Rumi’s A Great Wagon: “Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.” Here on the page we meet the author, but moreover: we meet ourselves and our fellow fated, and complicit, man.

Question 7 by Richard Flanagan is published by Allen & Unwin ($35) in Australia.