30 delicious chocolate facts for World Chocolate Day

A bittersweet story

beats1/Shutterstock

Chocolate has changed dramatically over the past 2,000 years, from its beginnings as a bitter drink to the sweet, creamy bars we eat today. It's also evolved from an actual form of currency in Mesoamerica (modern Central America and southern Mexico) to a huge global market, estimated to be worth around $133.6 billion (£104.7bn) in 2024. From its heavenly associations to the chocolate bar brands we know and devour with gusto today, here's a short but sweet history of chocolate.

Ahead of World Chocolate Day on 7 July, read on to discover the fascinating history of everyone’s favourite sweet treat.

Gift from the gods

BLACKDAY/Shutterstock

Experts believe chocolate has been around for at least two millennia, with evidence that cacao beans were consumed in some form by Mayan people, who lived in Mesoamerica more than 2,000 years ago. Some believe it can be traced back even further to the Olmec, the first major civilisation living in Mexico, dating from around 1600 BC. In both cultures, the cacao bean was sacred and considered to be a gift from the gods.

A prized elixir

dowraik/Shutterstock

Mayans would dry and grind cacao beans and mix them with chilli and water to form a bitter drink. Later, the Aztec people named this drink xocolatl – seen as the origin of the word 'chocolate'. It was considered to have spiritual and medicinal powers and warriors would drink it after battle to give them strength. Xocolatl was regularly used in religious ceremonies and was often offered as consolation to the soon-to-be sacrificed – as a result, the humble cacao bean became a form of currency.

A highly valued commodity

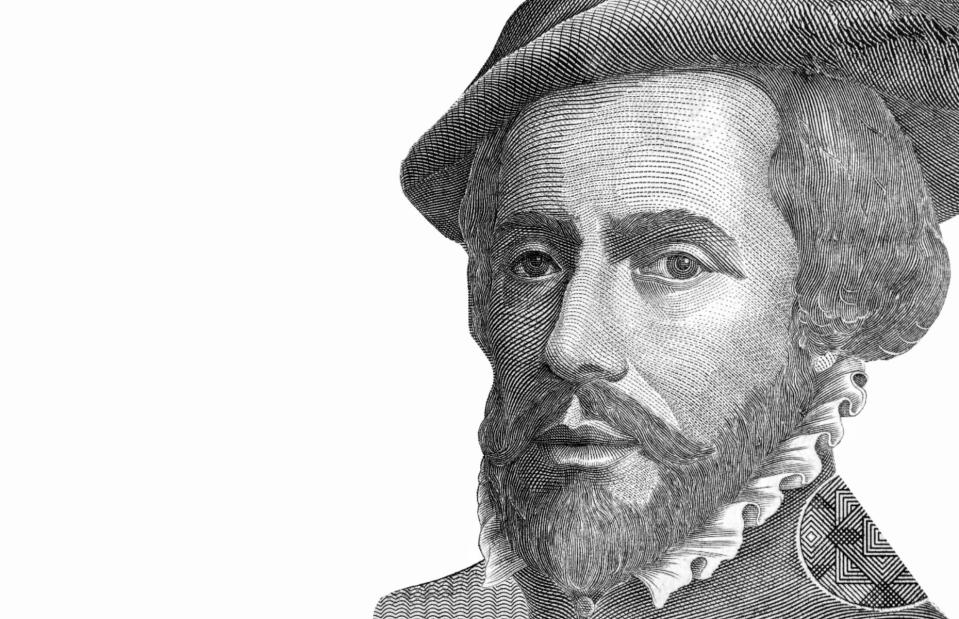

German Vizulis/Shutterstock

Cacao was so highly prized in Mesoamerica that access to it indicated status. The 16th-century Aztec ruler Montezuma II (depicted on a sketch here) was particularly partial to the bitter bean and allegedly drank 50 cups of xocolatl every day. The drink wasn't consumed by the masses, though. While those in the upper echelons of society enjoyed this predecessor to cocoa, most had to make do with a rudimentary cacao bean dish likened to porridge.

Chocolate goes global

Prachaya Roekdeethaweesab/Shutterstock

There are three theories as to how cacao beans first reached Europe. The most popular origin story tends to be that it was via Spaniard Hernán Cortés (depicted here), who travelled to Mesoamerica to establish colonies during the reign of Montezuma II (who, thanks to the Spanish conquests, turned out to be the last Aztec leader). He was so enamoured by xocolatl that, so the story goes, he brought beans back to Spain in 1528.

Columbus and cacao

Everett Collection/Shutterstock

Another theory is that Christopher Columbus was way ahead of his fellow explorer. Some believe that on one of his trips, the Italian coloniser intercepted a trade ship journeying to America. On board were cacao beans, which he seized and brought back with him to Spain in 1502.

Divine intervention

Janusz Pienkowski/Shutterstock

Because they travelled the world preaching to unconverted communities, clergymen were exposed to cacao beans and their uses relatively early on. Some believe cacao beans entered the court of King Philip II of Spain in the 16th century when friars presented Guatemalan Mayan people to the sovereign.

From medicinal to pleasurable

Triff/Shutterstock

As we know from the Mayans and Aztecs, cacao was consumed for its medicinal purposes. Wealthy European elites also started drinking xocolatl as a health drink that had the additional benefit of alluding to a certain social status. However, it was the Spanish who began sweetening the drink by adding cane sugar, cinnamon, honey and vanilla to the ground cacao, chilli, and water mix.

When cacao became cocoa

Graeme Kennedy/Shutterstock

There's often confusion between cocoa and cacao. The use of the former is believed to be a spelling mistake that stuck. English traders are thought to have mixed up the letters when labelling the beans for transport. Today, cacao tends to refer to the raw beans and cocoa the comforting hot drink.

Status symbol

Everett Collection/Shutterstock

Produce sourced from overseas, such as pineapples, often symbolised social status because they were expensive and hinted at disposable income. Chocolate and cacao beans were no different. Chocolate – still consumed primarily as a drink – was a luxury, and it was the aspirations of social climbers that propelled its popularity beyond Spain. Soon wealthy European households commonly had chocolate drink–making equipment in their kitchens.

The dark side of chocolate

Everett Collection/Shutterstock

The soaring popularity of chocolate hugely increased demand for cacao beans and encouraged European businessmen to set up plantations in hotter parts of the world. This led to the enslavement of thousands of people, who were forced to work long hours in terrible conditions in order to harvest and maintain the crops.

Back across the Atlantic

Yingna Cai/Shutterstock

European countries weren’t the only ones discovering the power of the cacao bean. Chocolate arrived in North America in 1641, landing in Florida on a Spanish-helmed ship, before making its way to Boston. It’s here that the first ever American chocolate house opened, enabling people of all classes to enjoy the drink. Within a century, the cocoa trade was booming among the American colonies.

Revolutionary rations

Heritage Images/Getty Images

The popularity of the cocoa bean had spread among the colonies under British rule in America, so when the Revolutionary War began in 1775, its importance remained. Soldiers regularly had chocolate among their rations and, when money was tight, some were paid in chocolate – a throwback to the cacao bean’s use as currency in Mesoamerica.

Moving onto solids

piyaphun phunyammalee/Shutterstock

Chocolate continued to be consumed in drink form into the 19th century. But things changed forever in 1828, with the invention of the cocoa press. It squeezed the fatty butter from roasted cacao beans to leave behind a powder that was then used to create solidified chocolate. It's thought this revolutionary equipment was invented by Coenraad Johannes van Houten or his father, Casparus. It meant that chocolate could be made at a cheaper price, increasing its accessibility to the public.

Raising the bar

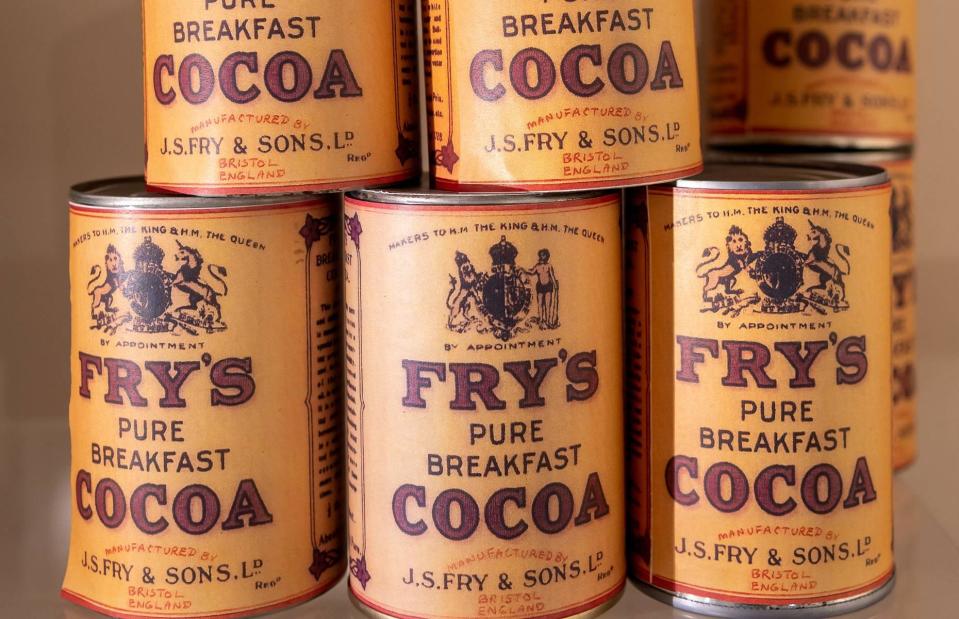

Tom Meaker/Shutterstock

It wasn't long before the first chocolate bar followed. It was in 1847, in fact, when cocoa powder was combined with cocoa butter and sugar to form a mild dark chocolate. The company behind this new product was British brand J.S. Fry & Sons, who set the wheels in motion for what was to become a global industry.

Swiss milk chocolate arrives

Fortyforks/Shutterstock

In 1875, Swiss chocolatier Daniel Peter decided to do something different with the now standard chocolate formulation. He mixed the cocoa powder with dehydrated milk to create a smoother texture, without greatly reducing the shelf life. From this, the first milk chocolate bar was born and Switzerland’s reputation as a home to luxury confectionary began.

Nestlé is born

Hi-Point/Shutterstock

When Daniel Peter created the world's first milk chocolate bar, he worked alongside Henri Nestlé – the inventor of powdered milk and founder of Nestlé. Of course, the business still exists today and is now one of the biggest producers of chocolate bars and sweets, with iconic brands such as KitKat, Smarties, Aero, Milkybar and Quality Street.

Cadbury gains royal approval

Everett Collection/Shutterstock

The chocolate market continued to grow as more brands entered the fray. In 1853, Cadbury became the sole official provider of cocoa and chocolate for Queen Victoria. Cadbury continued to supply the royal household with cocoa and chocolate under Queen Elizabeth II, who granted the company a Royal Warrant.

Easter eggs are hatched

Victorian Traditions/Shutterstock

Towards the end of the 19th century, chocolate was becoming much easier to mass produce – and to mould into shapes beyond the simple rectangular chocolate bar. Easter eggs had long been a symbol of Easter, but in 1873 they were created in chocolate form, launching a new tradition that remains in place today. J.S. Fry & Sons – the British brand that created the first chocolate bar – was behind this invention too.

Smooth operator

Pietersma/Shutterstock

Chocolate had come a long way since its humble beginnings as a ground-up cacao bean, but still suffered from a slightly chewy consistency. There was room in the growing market for further innovation and in 1879, Rodolphe Lindt stepped in. The Swiss chocolatier invented a chocolate conch machine, which essentially aerated the chocolate, to make it smoother. Rudolphe’s legacy remains in the various Lindt chocolates (and Easter bunnies) still so popular today.

A model village

David Hughes/Shutterstock

That same year, Bournville was born. Cadbury had outgrown its central Birmingham factory and brothers George and Richard Cadbury had the brainwave of moving into a rural area, with more space and better, healthier conditions for workers. A site was chosen on the outskirts of Birmingham and the first bricks were laid for the factory and workers' village in early 1879. The village would prove key in mass producing chocolate, as well as inspiring Cadbury’s Bournville chocolate. Tourists can still visit the factory today.

The rise of Hershey

George Sheldon/Shutterstock

Over in the US, Milton Hershey also built an entire factory town dedicated to producing chocolate. The Pennsylvania hub opened in 1894, following Hershey's success in building and selling a caramel candy company. Armed with an assembly line plan, Hershey was now able to produce chocolate on a major scale. The town of Hershey still exists, as does the chocolate.

Soft in the middle

Dyfrain/Shutterstock

Chocolatiers increasingly experimented with flavours, forms and consistencies. In 1913, Swiss innovator Jules Sechuad invented a machine that could insert fillings into chocolate bars. It meant that more flavours could be produced and made available to the public. Today, we see the results of this invention in chocolate bars with centres filled with the likes of Turkish delight, caramel, coffee, cream and much more.

Household names

Paul Maguire/Shutterstock

By the early 20th century, chocolate had become a byword for indulgence across the world. Brands that had moved into the market early were growing exponentially, and the likes of Cadbury (which merged with Fry's in 1919), Mars and Hershey had become household names.

Cocoa hits the stock exchange

nyker/Shutterstock

In the US, the chocolate industry had grown so strong that it needed more bodies to manage its growth. In 1925, the New York Cocoa Exchange was formed. Around the same time, and also in the US, the Chocolate Manufacturers Association (CMA) was formed to help manufacturers gain funding, research new products and liaise with government bodies.

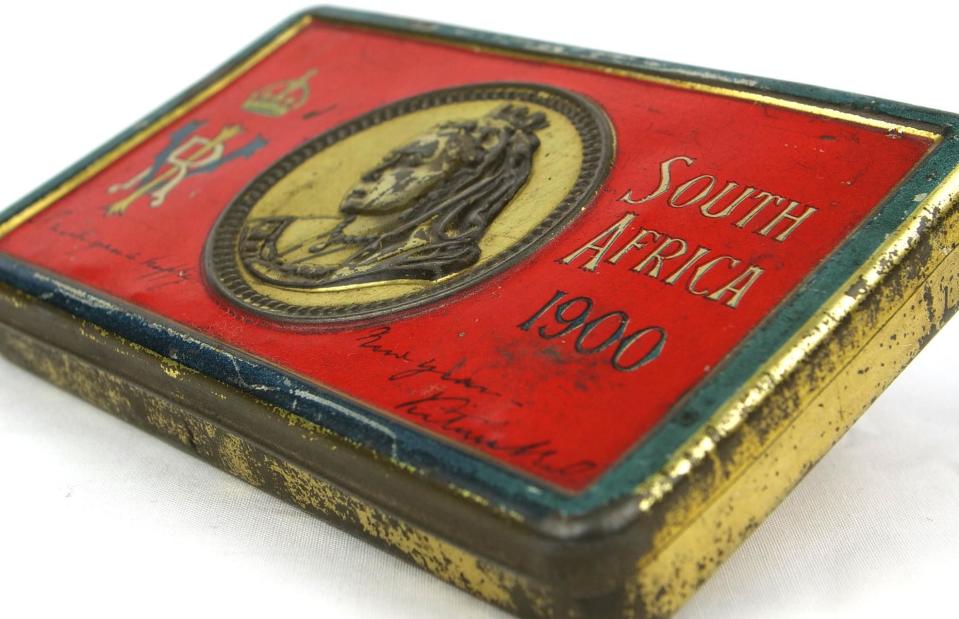

Chocolate for victory

Everett Collection/Shutterstock

In the Second World War, British soldiers were famously allocated chocolate as part of their rations. While people may not have shared the Mayan and Aztec belief that it possessed war-winning powers, it was seen as a morale booster for the troops.

Next level chocolate

Tupchienko Vladislav/Shutterstock

Chocolate designs have continued to become ever-more ambitious. Our appetite to see what master chocolatiers can achieve has continued to grow, with people tuning in to TV shows dedicated to chocolate innovations. In 2011, Thorntons decided to mark its 100th birthday by creating the world’s heaviest chocolate bar, weighing a whopping 12,770lbs (5,792kg).

Back to bitter

Sea Wave/Shutterstock

We’ve come full circle when it comes to dark chocolate. As in the Maya and Aztec civilisations, both its bitterness and its apparent health benefits are prized – some believe that regularly consuming dark chocolate can help lower blood pressure. However, experts do also warn that chocolate contains a lot of fat and should be consumed in moderation.

Moving to a fairer trade

Annet_ka/Shutterstock

While chocolate is of course incredibly popular, there’s a darker side to the industry. Mass production of chocolate began a dependence on the labour of enslaved or poorly paid workers. In 2004, Fairtrade International was set up to tackle exploitation across multiple industries including cocoa. Now many prominent chocolate brands have subscribed to fairer practices.

Sustainable chocolate

Joseph Sorrentino/Shutterstock

In recent decades, consumers have become much more aware of how farming cocoa can impact the environment. Vast plantations and mass farming has led to almost irreversible levels of deforestation in certain parts of the world. Now, brands are facing increasing pressure to source ingredients sustainably, with a new sector of ethical products.

Spoilt for choice

monticello/Shutterstock

Since the humble cacao bean was first harvested in Mesoamerica more than 2,000 years ago, innovation around its consumption hasn’t stopped. Now, there’s more choice in the market than ever before, whether that be classic favourites, vegan versions, ethical products or intricate chocolate sculptures. Whatever form it takes, though, it's clear the sweet stuff is here to stay.

Now discover the world’s best desserts that everyone should try