Bizarre British foods the rest of the world don't understand

How many would you try?

Robyn Mackenzie/Shutterstock

Known for its comforting, though not always colourful, qualities, British food is often seen as one of the less exciting cuisines in the mix. Yet there are plenty of weird and wonderful traditional dishes that challenge that image. From the fancy to the frugal, the slightly strange to the stomach-churning and the delicious to the downright alarming, these are the most bizarre British foods of all time.

Read on to see some of the most bizarre British foods ever created (and eaten), counting down to the most unusual – and deadly – of them all.

24. Welsh rarebit

locrifa/Shutterstock

There are few simple dishes that are quite so indulgent as Welsh rarebit. Initially known as Welsh rabbit – despite a distinct lack of rabbit in the ingredients list – and born in the 18th century, this dish sees a molten cheese sauce, flavoured with mustard, Worcestershire sauce and often stout or ale, poured over toasted bread and grilled until golden and bubbling. When topped with a fried or poached egg, Welsh rarebit becomes buck rabbit.

23. Tipsy laird

Anna Shepulova/Shutterstock

The Scottish version of a classic trifle sees the sponge element soaked in whisky rather than sherry. Proudly served on celebratory occasions – think Christmas, Burns Night and Hogmanay – the ‘tipsy’ in the title of this indulgent dessert refers to said liquor, while 'laird' is the Scottish word for lord. A truly patriotic Scot would ensure that the berries used to garnish this boozy dessert were sourced from Caledonian soil, too.

22. Jam roly-poly

Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock

A traditional British school dinner favourite that dates back to the Middle Ages, sweet and stodgy jam roly-poly sees suet pastry rolled out, covered in fruit jam and rolled up again. The swirl of red and white is then steam-baked, sliced and served with hot custard. The dessert also goes by the names ‘dead man’s arm’ and ‘shirt sleeve pudding’, because in the early days it would often be steamed in an old shirt sleeve or stocking.

21. Pigs in blankets

Dron G/Shutterstock

Rarely seen at other times of year, pigs in blankets are a Christmas staple for many Brits. Also known as 'kilted soldiers', chipolata sausages (the pigs) are wrapped in streaky bacon (their blankets) and cooked until the bacon is crisp and the sausages juicy. The first recipes for pigs in blankets appeared in the 1950s, but they were really popularised by Delia Smith in the 1990s. Nowadays they form an integral part of the traditional turkey feast and make fabulous festive canapés, too.

20. Bubble and squeak

Fanfo/Shutterstock

With an enigmatic name that offers next to no hints as to its ingredients list, bubble and squeak was invented as a thrifty yet tasty 18th-century means of reducing food waste. Made using leftover vegetables from a Sunday roast (think cabbage, carrots, swede and onions), all bound together with mashed potato and fried until crisp and golden on the outside, bubble and squeak is even better with a fried egg placed on top. In Ireland, a similar dish made from mashed potatoes, cabbage or kale and onions is known as colcannon, while in Scotland, a cheesy version goes by the moniker rumbledethumps.

19. Toad in the hole

Donna Gibbs-Williams/Shutterstock

Toad in the hole was originally created as a means for making meat stretch further in poor households (and is, thankfully, always devoid of toads). The doyenne of British cooking, Isabella Beeton, was right when she described this as a ‘homely and savoury dish’. She suggested preparing the batter pudding with rump steak and lambs' kidneys, while English cookery writer Hannah Glasse made the case for pigeon in her 1747 book The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy. Modern versions tend to favour a sausage-studded batter, with the presence of onion gravy being non-negotiable for many.

18. Carrot scones

M Shev/Shutterstock

While vegetables in a scone mix might initially sound alarming, this one makes perfect sense. Easy to grow, packed with vitamins and with a slight sweetness about them, carrots were frequently used in wartime cooking, featuring in baked puddings, cakes and desserts. In her 1995 compilation, The Victory Cookbook, British broadcaster, home economist and food writer Marguerite Patten shared a recipe for this simple treat, which only called for a few basic ingredients – carrots included.

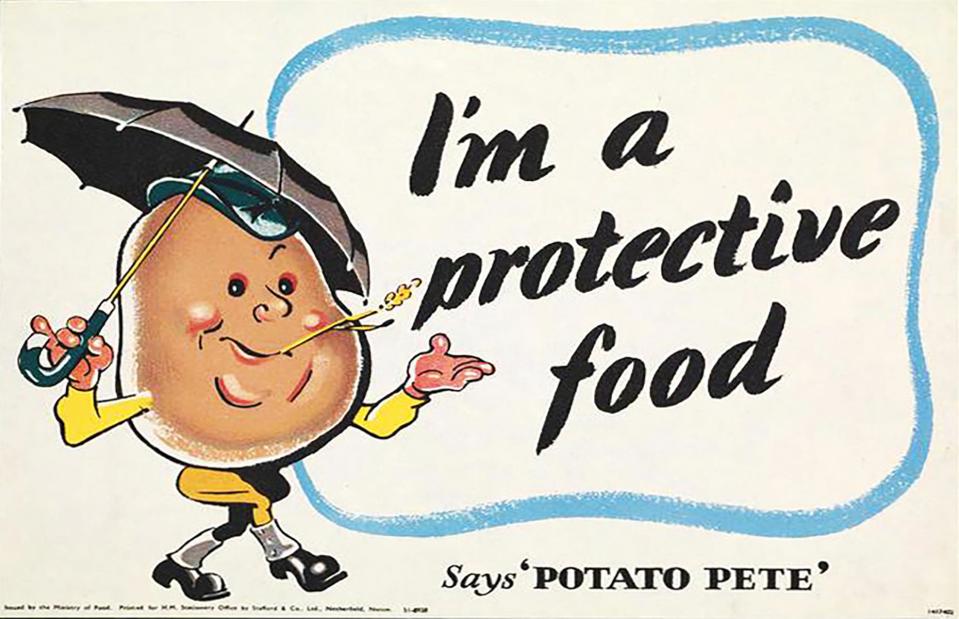

17. Potato piglets

Ministry of Food/Wikimedia Commons

Involving a cored potato stuffed with sausage meat and baked, this straightforward dish was introduced by the Ministry of Food during the Second World War, as part of a Dig for Victory campaign to help people make the most of available rations and reduce food waste. Leaflets featuring Potato Pete, a cartoon character promoting the benefits of the humble potato, explained how to make the 'piglets' and suggested serving them on a bed of cooked cabbage.

16. Pease pudding

AS Foodstudio/Shutterstock

As an old nursery rhyme goes: 'Pease pudding hot, pease pudding cold, pease pudding in the pot, nine days old…' It attests to the versatility and shelf life of this medieval stalwart, which is made by boiling dried yellow split peas with herbs, vegetables and vinegar, to achieve a paste-like consistency. Pease pudding is still eaten with gusto in northeast England, where it's most often served with thick slices of ham or gammon and lashings of parsley sauce.

15. Black pudding

Robyn Mackenzie/Shutterstock

A sausage traditionally made from pork offal, oatmeal, seasoning and spices all held together with pigs’ blood, black pudding is a dish firmly ensconced in British culinary history, and has been enjoyed since at least the 15th century. It’s most often found sliced and fried as part of a proper English breakfast but, thanks to its rich taste, it’s also used to add depth of flavour to soups, stews and stuffings.

14. Bedfordshire clanger

Chatham172/Shutterstock

This clever dish was born out of convenience, when savvy 19th-century women produced the hand-held meal for their farm labourer husbands to take for lunch. The long, pasty-like suet dumpling features a savoury filling – typically meat, potatoes and vegetables – at one end, with something sweet such as jam or fruit at the other. The latter is scored to identify it as dessert, ensuring everything is eaten in the right order. Crusts were always discarded back in the day, as their purpose was simply to contain the filling and protect it from dirty hands.

13. Cucumber ice cream

The Hustle/Wikimedia Commons

Long before Heston Blumenthal caused a stir with the likes of bacon and eggs ice cream, London cookery writer and entrepreneur Agnes Marshall (pictured) was already pushing boundaries with liquid nitrogen and the like. Known as the ‘Queen of Ices’, and believed to have invented the ice cream cone, in her 1885 The Book of Ices the forward-thinking Agnes recommended making ice cream with puréed cucumber, sugar, ginger brandy, lemon juice and sweetened cream or custard. It was a riff on the popular dinner party dish of the time, cooked cucumber.

12. Parmo

AS Foodstudio/Shutterstock

Also known as Teesside Parmesan, this cult delicacy has been a firm favourite in Middlesbrough, North Yorkshire since the 1960s. The name Parmo refers to the American chicken Parmesan, inspired in turn by the Italian melanzane alla parmigiana. To make the British version of the dish, a chicken or pork cutlet is flattened, coated in breadcrumbs and deep-fried until golden before being covered with béchamel sauce and melted cheese.

11. Beef olives

Serge Bertasius/Shutterstock

This strangely named bastion of British cuisine is a nostalgic, slow-cooked number that has been made for centuries by wrapping slivers of beef around sausage meat, breadcrumbs and herbs (not an olive in sight). As cookery writer Hannah Glasse suggested, the name could be a nod to the phrase ‘to olive’, meaning to stuff something like an olive and referring to a technique used to impress dinner guests in the 1700s. Once rolled, beef olives are browned and simmered in a rich gravy until tender.

10. Scotch woodcock

Fanfo/Shutterstock

Early mentions of Scotch woodcock – softly set scrambled eggs on toast topped with anchovies or Gentlemen’s Relish – can be found in Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management. Often served in the Victorian and Edwardian eras as a savoury (a digestive course offered at the end or towards the end of a meal), Scotch woodcock still featured on the menu at the House of Commons until the 1950s.

9. Pickled eggs

Watson Creation/Shutterstock

Pickled eggs are a simple but well-loved stalwart of British snacking culture, most often to be found in large jars behind the bar at pubs and on shelves at fish and chip shops. There’s nothing fancy going on here; peeled hard-boiled eggs are cured in a vinegary brine, which they’re then left to sit in, with the pickle preserving the eggs for several months. Salty, simple and satisfying.

8. Bread and dripping

Axel Bueckert/Shutterstock

Dripping is the fat that renders away when beef is roasted. The idea of eating cooking fat as a snack, spread on toast and sprinkled with salt and pepper, became popular among the working class in the 20th century. Another variation on the idea is mucky fat, a thick, set gravy that’s made from the meat juices left behind in the roasting pan, and often used to cook roast potatoes or to make sandwiches known as mucky fat butties.

7. Laverbread

David Pimborough/Shutterstock

Rather misleadingly, there’s no bread involved in this Welsh delicacy, that's also known as ‘Welshman’s caviar’. A dark green paste made from boiled seaweed, laverbread has been enjoyed since the 17th century. Boasting a distinctive, salty flavour due to its iodine content (some liken the taste to that of olives or oysters), laverbread is often coated in oatmeal and fried or served with bacon and cockles as an essential part of a Welsh breakfast.

6. Frog legs

Alesia.Bierliezova/Shutterstock

Although frog legs are often parodied as quintessentially Gallic fare, in 2013 a group of archaeologists discovered cooked frog bones during an excavation of an ancient site near Stonehenge, England. These findings suggested that the British had likely been tucking into frog legs as far back as 7596 BC – well before the first known documentation of French folk feasting on them.

5. Stargazy pie

David Dorss/Shutterstock

Stargazy pie distinguishes itself from all other pies thanks to the clutch of fish heads (most commonly pilchards or herrings) sticking out of the pastry lid, as if gazing up at the stars. The origins of the pie (which features a creamy filling made from egg, bacon and potatoes) can be traced back to the Cornish fishing village of Mousehole. Legend has it that, with the village short on food due to winter storms, a brave fisherman named Tom Bawcock set sail and returned with a mighty haul that was quickly turned into a huge pie. His bravery is celebrated each year on 23 December – Tom Bawcock’s Eve – with, you’ve guessed it, stargazy pies a-plenty.

4. Haggis

Stock Creations/Shutterstock

Scotland is responsible for a fair few of Britain’s more unusual foods (here’s looking at you, battered, deep-fried Mars Bar), but this one might just be the most divisive. The country's national dish is traditionally made from sheep’s pluck (minced heart, liver and lungs), which is combined with oatmeal, onions, suet and spices and cooked in a sheep’s stomach. Served with neeps and tatties (mashed turnips and potatoes), it's an essential part of Burns Night celebrations, when the haggis itself is serenaded with Robert Burns’ famous poem, Address to a Haggis.

3. Ham in aspic

Oleg Panda Boev/Shutterstock

Synonymous with Fanny Cradock's cooking, aspic is a savoury jelly made by slowly cooking meat to produce a natural gelatine that thickens when cooled, and can be used to encase and preserve cold ingredients. No fancy 1950s dinner party would have been considered complete without a towering centrepiece featuring intricately presented meat, seafood, vegetables or hard-boiled eggs housed in a transparent aspic coating. Aspic dates back much further, though; one of the earliest Arabic cookbooks mentions an aspic called qaris, made by boiling fish heads with vinegar, parsley, onions and aromatics.

2. Jellied eels

Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock

While certainly not as popular as they were in Victorian times – when the River Thames teemed with the fish, and eels cooked and cooled in their own gelatinous stock were a cheap city favourite – there’s still a place for this snack in many a Londoner’s heart. In fact, it would be remiss to visit an East End pie and mash shop without tucking into a plate piled high with pie, mashed potatoes and jellied eels.

1. Poisonous purple pears

vengerof/Shutterstock

In the Georgian period, a recipe published in Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Simple caused quite the impact, and not for reasons intended. The maker was instructed to peel and quarter pears and stew them with cloves, lemon peel, sugar and red wine in a pewter dish; the idea here was that the acid in the pears would react with the lead in the dish and turn the pears an appealing shade of purple. However, the colour came at a pretty price; once infused, the fruit became poisonous – and, in some cases, proved deadly to diners.

Now discover the world's weirdest foods that taste fantastic