How WWI played a key role shaping plastic surgery and modern anaesthesia

The metrics from the First World War are horrific. Estimates vary, but in all, there were about 40 million military and civilian casualties – 20 million dead and 21 million wounded. Never before had a conflict brought such devastation in terms of death and injury. In response, during the four years of the war, military surgeons developed new techniques on the battlefield and in supporting hospitals, which, in the war’s final two years, resulted in more survivors of injuries that would have proved mortal in the first two.

On the western front, 1.6 million British soldiers were successfully treated and returned to the trenches. By the end of the war, 735,487 British troops had been discharged following major injuries. The majority of the injuries were caused by shell blasts and shrapnel.

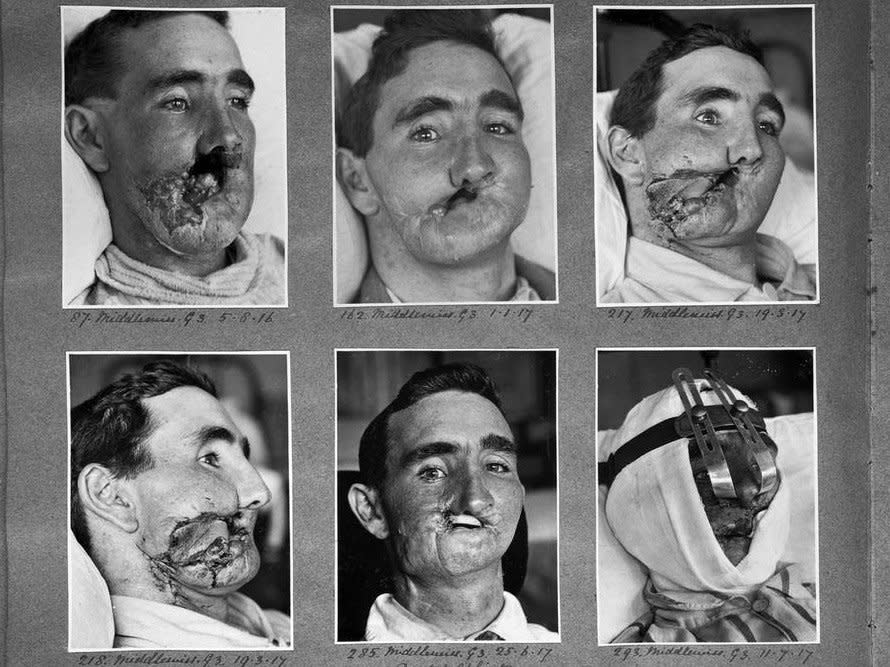

Many of the injured (16 per cent) had injuries affecting the face, more than a third of which were categorised as “severe”. Historically, this was an area where very little had been attempted, and survivors with major facial injuries were left with major deformities that made it difficult to see, breathe easily, or eat and drink.

A young ENT (ear, nose and throat) surgeon from New Zealand, Harold Gillies, working on the Western Front, saw attempts to repair the ravages of facial injuries and realised that there was a need for specialised work. The timing was right, because the military medical leadership was recognising the benefit of establishing specialist centres for dealing with specific injuries and wounds, such as neurosurgical and orthopaedic injuries or victims of gassing.

Gillies was given the go-ahead, and by January 1916 was setting up Britain’s first plastic surgery unit at the Cambridge Military Hospital in Aldershot. Gillies toured base hospitals in France to seek suitable patients to be sent to his unit. He returned expecting about 200 patients – but the opening of the unit coincided with the opening of the Somme offensive in 1916, and more than 2,000 patients with facial injuries were sent to Aldershot. Treatment was also needed for sailors and airmen suffering from facial burns.

A strange new art

Gillies described the development of plastic surgery as a “strange new art”. Many techniques were developed by trial and error, although some mirrored work that had been done centuries previously in India. One of the main techniques Gillies developed was tube pedicle skin-grafting.

A flap of skin was separated but not detached from a healthy part of the soldier’s body, stitched into a tube, and then sutured to the injured area. A period of time was needed to allow a new blood supply to form at the site of implantation. It was then detached, the tube opened and the flat skin stitched over the area that needed cover.

One of the first patients to be treated was Walter Yeo, gunnery warrant officer on HMS Warspite. Yeo sustained facial injuries during the Battle of Jutland in 1916, including the loss of his upper and lower eyelids. The tube pedicle produced a “mask” of skin grafted across his face and eyes, producing new eyelids. The results, although far from perfect, meant that he had a face once again. Gillies went on to repeat the same sort of procedure on thousands of others.

There was need for larger facilities for surgical and postoperative treatment and also rehabilitation of the patients, together with the different specialities involved in their care. Gillies played a large part in the design of a specialist unit at Queen Mary’s Hospital in Sidcup, southeast London. It opened with 320 beds – and by the end of the war, there were more 600 beds and 11,752 operations had been carried out. But reconstructive surgery continued long after hostilities ceased, with some 8,000 military personnel treated between 1920 and 1925. The unit finally closed in 1929.

The details of the injuries, the operations to correct them and the final outcomes were all recorded in detail, both by early clinical photography and also by detailed drawings and paintings created by Henry Tonks who, although trained as a doctor, had given up medicine for painting. Tonks became a war artist on the Western Front but then joined Gillies to help not only in the recording of the new plastic procedures, but also with their planning.

The only real advances

The complex facial and head surgery necessitated new ways of delivering anaesthetics. Anaesthesia generally had advanced as a speciality during the war years – both in the way it was administered, and also how doctors were trained (previously, anaesthetics had often been given by a junior member of the surgical team).

The survival from operations requiring anaesthesia was improving, although techniques were still based on chloroform and ether. The Queen Mary’s anaesthetic team developed a method of passing a rubber tube from the nose to the trachea (windpipe), as well as working on the endotracheal tube (mouth to trachea), which was made from commercial rubber tubing. Many of their techniques remain in use today. As an Austrian doctor wrote in 1935: “Nobody won the last war but the medical services. The increase in knowledge was the sole determinable gain for mankind in a devastating catastrophe.”

Robert Kirby is a professor of clinical education and surgery at Keele University. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Norman G Kirby, Major General (Retired), Director of Army Surgery 1978-82