The fascinating history of Fleet Street

The birth of the modern newspaper can be traced to a house that once stood on the eastern bank of the fetid River Fleet in London. From 1702, overlooking the sewage, dead dogs, and suicide victims that clogged up the waterway, England’s first daily newspaper, the Daily Courant, thumped, clanged and squelched out the news to the city's eager citizens.

It was just one product of a media revolution at the dawn of the 18th century. For reasons that will become clear, England’s strict pre-publication censorship laws melted away in 1695 and within months a prolific newspaper press had burst into life. By the mid-1730s, 31 papers - six dailies, 12 tri-weeklies and 13 weeklies - were being hawked on the streets of London, with an average combined weekly circulation of 100,000. Contemporaries assumed that each issue was read or heard by 20 people in taverns, coffeehouses, barber shops and elsewhere, suggesting that by the mid-1740s, some 42 per cent of London’s 650,000-strong population consumed news daily.

The press boom triggered a new addiction, something the journalist Joseph Addison defined in 1712 as a “news frenzy”. This gripped the middle classes, who spent three half-pennies to buy newspapers outright, but also those further down the social pyramid. Foreign visitors thought it remarkable. In the 1720s Swiss tourist César de Saussure observed how London workmen “habitually begin the day by going to coffee-rooms in order to read the latest news”; a Prussian visitor found it surreal that even fish-mongers read and discussed papers assiduously. In London, literacy rates were unusually high - around 55 per cent for men and 30 per cent for women in 1700 - but illiteracy was no barrier for news junkies. They’d simply huddle around people who could read and beg them to read a paper aloud.

The Victorians liked to hail ‘the fourth estate’ as a pillar of British liberty but England’s censorship laws expired almost by accident. The rival Tory and Whig parties simply didn’t trust one another to censor the press in a non-partisan fashion; press freedom became a necessary evil. Proposals to reintroduce curbs on the freedom of the press were considered in 1712 but came to nothing. By then, the idea of refuting rather than repressing critical or controversial views was woven into the fabric of political culture. Even the fearsome government censor Sir Roger l’Estrange eventually conceded: “Tis the press that has made ‘em mad, and the press must set ‘em right again” - quite an admission for a man once known as “the bloodhound of the press” for the way he had persecuted “seditious” authors with zest and glee.

After 1695, journalists were free to criticise government policy or satirise the Church without ending up pilloried, gaoled, or having various body parts chopped off (as was the case before, and still was the case in France). That’s not to say Britain enjoyed a universal freedom of the press, but in the early 18th century London boasted the biggest, freest and most profitable press in the world.

It was along a muddy, traffic-choked thoroughfare between Temple Bar and Fleet Bridge, amidst the whirl of crowds and commerce, that newspaper printing houses set up shop after 1695. Many remained there until the late 20th century. The melodic cries of newspaper hawkers - Flying Post! Post Boy! Daily Courant! Post Man! Gazette! Examiner! - mingled with the bell-chimes of St Bride’s (still known as the journalists’ church), the rattling of coaches and the shopkeeper’s cry of “What do ye lack?” The main street was lined with high-end shops and Fleet Bridge was cluttered with grotty shacks where one-eyed men hawked nuts, gingerbreads, oranges and oysters, as The London Spy observed in 1699.

It was an ideal location for the London press. Fleet Street and Ludgate Hill had a long tradition of publishing - London’s first printing house had opened in Stationer’s Court in the 15th century - and St Paul’s churchyard was a thriving marketplace for booksellers. Ever since Tudor times, “that tippling street, distinguished by the name of Fleet” was renowned for its profusion of ale-houses and taverns and by 1700 there were 26 coffeehouses too. Because Fleet Street was one of London’s main arteries transporting people and mail between Westminster and the City, these became lightning rods for political, financial, and overseas news.

Journalists capitalised upon this and would mingle and eavesdrop in local establishments, returning to their offices with fresh gossip. Here, editors sifted through what their reporters had gathered looking for good copy for their four to six pages, each containing two columns of tightly packed news with no headlines or illustrations. Stories were carefully selected not just to sell papers but to ensure people read the classified sections, which usually generated at least 50 per cent of a paper’s revenue. If advertisers pulled out, papers went bust.

For Fleet Street editors, the best way of building up and sustaining a loyal readership was to make their coverage as partisan as possible. By the time the tri-weekly or even daily newspapers were published, most people were already familiar with big stories - like the strange death of the lions in the Tower (Post Boy, January 1712), the appearance of a glowing comet above Lincoln’s Inn Fields (Robin’s Last Shift, March 1716), or the mutilation of British merchants by Spanish pirates in the Atlantic (London Evening Post, October 1737) - via word-of-mouth. To stay relevant, editors had to give their readers something new: spin. Londoners dismissed ‘balanced’ papers as phoney and bland, slants needed to be bold and vivid.

Partisan approaches were rarely adopted out of genuine political conviction. In spite of posthumous attempts to glorify newspapers as vessels of truth and enlightenment (the titles Sun, Star, Mirror, Guardian capture something of this), 18th-century Fleet Street was unprincipled, devious and corrupt. Plagiarism was rife, taking bribes from ministers was common and early hacks like Daniel Defoe sold their pen to the highest bidder.

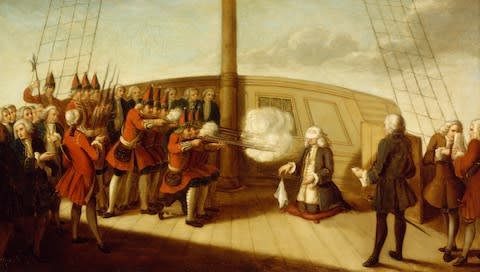

Editors cared little for the moral consequences of their campaigns. In outraged weekly doses in 1757, the Monitor bayed for the blood of Admiral Byng, a competent naval commander who had retreated from a vastly stronger and better-equipped French fleet in 1756, losing British Minorca as a result. He was unequivocally not to blame yet the Monitor relentlessly portrayed him as a despicable coward and traitor who ought to be executed immediately.

One Londoner was so horrified by this media witch hunt that he was compelled to write a poem in his diary castigating the Monitor as a “merciless moulder of judgement and death.” He wrote: “Byng must be dispatched; and it does mighty well, for the mob to be pleased and the paper to sell”. The media got their scalp: Byng was executed by firing squad two days after the Monitor’s latest tirade; a ‘lullaby’, as another reader put it, to quell the wrath of the news media and its frenzied readers.

With its nakedly partisan character, the press mainly preached to the converted and rarely tried to win people around to new political world-views. Rather it reinforced what people already believed, fanning the flames of their political beliefs, assimilating events into rival political world-views and crystallising pre-existing prejudices. Politicians miscalculated the relationship between the press and political beliefs. Robert Walpole spent the colossal sum of £50,000 funding pro-government rags but it didn’t win him many new supporters.

Today, Fleet Street is a pale imitation of its former self. The printing offices have been replaces by blue plaques (including one for the Courant), many newspaper circulations are in decline and press freedoms have been under serious review for the first time in centuries. But it’s testament to the impact of the 18th-century media boom that ‘Fleet Street’ endures as a metonym for the newspaper industry - even though no newspaper is printed there.

London historian Dr Matthew Green is the co-founder of Unreal City Audio, which produces historical tours of London as audio downloads and live events.