Why you should skip the Lake District and head instead to humble Barrow-in-Furness

In early August 1914, newlyweds DH and Frieda Lawrence were on a walking tour of Westmoreland with three friends when they “came down to Barrow on Furness [sic], and saw that war was declared… and Messrs Vickers [and] Maxim call in their workmen – and the great notices on Vickers’ gateways – and the thousands of men streaming over the bridge.. and the amazing, vivid, visionary beauty of everything, heightened by the immense pain everywhere.”

So Lawrence wrote in a letter to Lady Cynthia Asquith, capturing the contrast and sheer strangeness of moving from Lakeland fells to England’s edge, from Westmoreland to Lancashire, from nature’s peace to the human industry of war.

Barrow stands a few miles south of the mouth of the River Duddon on the seaward side of the Furness Peninsula. The town is 35 miles by wiggling A-road from the M6 and sits at the end of what has been called the longest cul-de-sac in Britain. Yet, just east of Barrow, in Morecambe Bay, is the UK’s centroid, or geometrical centre.

In many ways it is a place set apart, inside the modern county of Cumbria, but by accent and history part of Lonsdale in Lancashire – the ancient palatinate to which Barrow historically belonged. Coniston Water was only siphoned into Cumbria in 1974. For centuries, before trains and road tunnels linked things up, the Furness and Cartmel peninsulas were accessed by sea or across the Sands of Morecambe Bay.

The name Barrow comes from the Old Norse for “bare island”, Furness means “rump at the headland”. An Anglo-Saxon earl resided on Piel Island, later ceded to monks who built a harbour for shipping and storing grain, wine and wool. Their fortified warehouse grew into a castle, the 14th-century ruins of which are looked after by English Heritage. From spring through autumn, local firms Piel Ferry and Piel Island Ferry run boat trips to the site and a grey seal colony.

“Of havoc tired and rash undoing, Man left this Structure to become Time’s prey,” wrote Wordsworth of Furness Abbey, back on the peninsula. Further inland, near Ulverston, is Swarthmoor Hall, an Elizabethan stately home with important links to the Quaker movement.

The industrial past of Barrow-in-Furness lies everywhere. Iron ore had been shipped through the port for decades but the founding of the Haematite Iron and Steel Works at Barrow in 1859 set off a boom; Barrow would later be the site of the largest steelworks in the world. During the 1880s salt was discovered by chance on Walney Island while boring for coal and the Barrow Salt Works became a major operation.

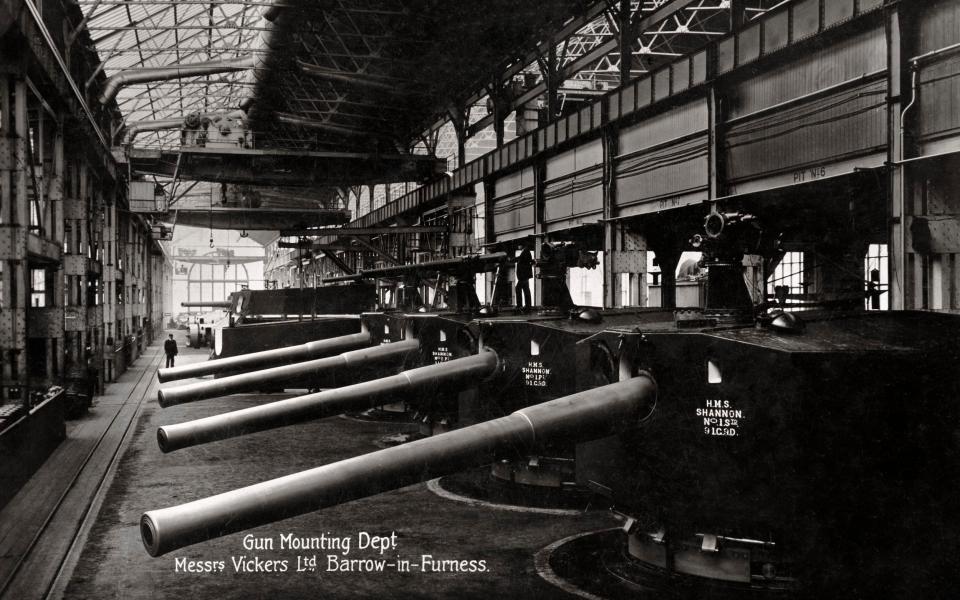

Walney forms a natural breakwater around Barrow, conditions ideal for a shipyard. Shipbuilding, which took off in the 1870s, was subsequently later taken over by Vickers. In 1901 the Royal Navy’s first submarine, HMS Holland 1 (aka Torpedo Boat No 1) was launched. The planned Vickerstown Estate was built between 1900 and 1906 to house employees. Its main artery, Powerful Street, takes its name from the Barrow-built ship HMS Powerful.

Barrow was nicknamed “The English Chicago”, though one commentator described it as a “combination in appearance of Birkenhead and a goldfinders’ city on the edge of one of the western prairies of America”. Nonetheless, the town has some city-like Victorian and Edwardian buildings along its tree-lined avenues, including the Town Hall, Custom House, Beaux-Arts public library and Gothic revival Duke of Edinburgh Hotel, built in the Belle Epoque 1870s, where Cary Grant and Charlie Chaplin were accommodated.

Lancashire is littered with post-industrial graveyards. This isn’t one. Today, Barrow is home to the Maritime–Submarine division of BAE Systems, the multinational arms maker that builds and maintains the Royal Navy’s Vanguard-class subs. The town has nearly four times the national average of manufacturing jobs. One of the UK’s early offshore wind farms opened off Barrow in July 2006. Now there are five, including the 56-square-mile Walney extension, for a time the biggest in the world of its type.

Barrow’s population grew from a meagre 150 in 1843 to 56,625 in 1901 – a Chicago-esque boom for sure. Today there are around 67,000 Barrovians. BAE, like Vickers before it, draws employees from all over the country. In 2008, a survey commissioned by website locallife.co.uk identified Barrow as the “most working class town in the UK”, on the dubious basis that it had a fish-and-chip shop, working men’s club, bookmaker, greyhound track or trade union office for every 2,917 of its residents.

We began with DH Lawrence, and shall end on a literary note – actually, two. For, while the Lakes has given us, along with overtourism, Wainwright-baggers and Kendal Mint Cake, the purple poetry and prose of Wordsworth and Ruskin, Barrow can vaunt its own stellar scribe: the Portuguese avant-garde poet Álvaro de Campos (1890–1935), a pseudonym of Fernando Pessoa.

Responding to Wordsworth’s Duddon sonnets, de Campos offers us his Barrow-on-Furness [sic], supposedly the ruminations of a much-travelled Portuguese engineer who finds himself sat on a drum in the docks, melancholy and adrift. Pessoa may have learned about the town after seeing Barrow-built ships docked in Lisbon.

A more familiar writer associated with Barrow-in-Furness is the Rev. Wilbert Awdry. Walney Island, said to be the windiest lowland spot in Britain, was the template for Sodor, about which Thomas the Tank Engine chuffed with his many pals. In Awdry’s imagination, the island grew to outlandish proportions, occupying a vast area of the Irish Sea between Barrow and the Isle of Man.

On a visit to the latter, Awdry had seen that the name of the ecclesiastical district was the Diocese of Sodor and Man – Sodor being a derivative of the Old Norse for the “southern” reaches of the Viking’s island possessions that included the Hebrides. In the books, Sodor has its own language, economic riches that Forbes compared to Silicon Valley, and more railways than the Indian subcontinent.

Walney has nature reserves and a coast path. For a more adventurous hike, follow the Duddon to its source on Wrynose Fell, near the point where the boundaries of Cumberland, Westmoreland, and Lancashire once converged – making it the defining river of the Lakes.

Or, if you fancy a big community-led charity tramp, join the 40-mile K2B walk this May. Afterwards, catch the Cumbrian Coast Line train back to Barrow-in-Furness, with slow onward connections to Sellafield but excellent ones to Tidmouth, Suddery, Ffarquhar and Vicarstown.