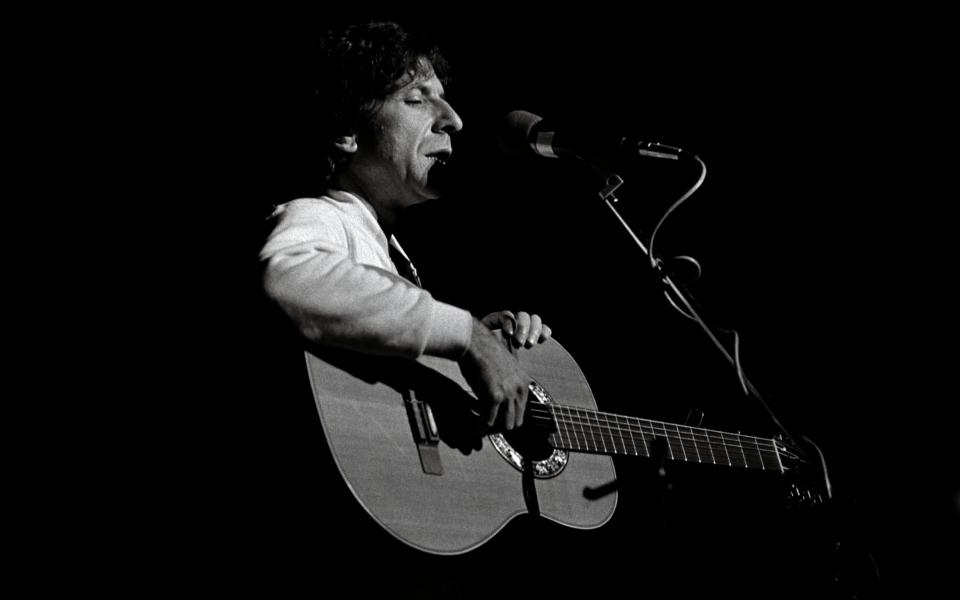

‘He went through women like water’: Leonard Cohen, the unlikely lothario

Leonard Cohen was the master of darkly romantic lyrics. The Canadian singer, who died in 2016 aged 82, imbued songs such as Chelsea Hotel #2, Sisters of Mercy and So Long, Marianne with intense passion that was by turns beautiful, elegiac, bleak and explicit. His desires burned deeply, too. “If you want a lover / I’ll do anything you ask me to,” he sang in his famously drawled baritone on 1988’s I’m Your Man.

But a new book about Cohen lays bare just how tangled, busy and occasionally destructive his love life really was. Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years, by journalist and author Michael Posner, charts his rise from struggling poet and novelist in the late 1950s to the start of his first international tour as a singer in 1970. Written as an oral history, it’s the first of three volumes which are based on over 500 interviews with people who knew Cohen.

What emerges is the picture of an extraordinary talent who was also a compulsive womaniser, a commitment-phobe and a cheat. The book is a dizzying account of the interplay between ardour and art. A succession of women, from on-off partner Marianne Ihlen to dancer Suzanne Verdal to singer Janis Joplin, acted as Cohen’s muses – this much we’ve always known. But the extent to which he played the field may surprise even the most ardent Cohen-ologist.

He was “a master seducer” who “went through women like water”, according to accounts in the book. “Beautiful, wild women… swarmed around Leonard,” recalls Aviva Layton, a friend of the singer’s for fifty years. When Posner writes that the singer was “pursuing every pretty woman he saw”, you feel there’s not much exaggeration involved.

He dated everyone from Joni Mitchell to fellow Montrealer Judy Greenblatt, who moved to London and married Vivian Baron Cohen and became grandmother to comedian Sacha Baron Cohen. “You couldn’t keep track of Cohen’s women,” a TV producer friend called Bernie Rothman told Posner.

Posner paints a picture of a man who was both a product of his time yet also slightly ahead of it. Born to a wealthy Jewish family in the Westmount neighbourhood of Montreal in 1934, Cohen resisted entering the family’s textile business and forged an unmapped path as a poet in the slowly emerging bohemia of the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Cohen cast a spell on women. His attraction lay in what he represented: he was both outsider and prodigy. His first book of poetry, Let Us Compare Mythologies, was published in May 1956 and contained 44 poems written between his 15th and his 21st birthday.

But his magnetism also stemmed from immense charisma. His quiet charm, intellect and intensity drew people to him. “It was like moths to a flame,” says one former girlfriend, Michele Hendlisz Cohen. His need to be loved may in part have stemmed from insecurities about his physical appearance; he was short and “wasn’t that great looking and didn’t have a great body”, as one person describes him in Posner’s book. But such shortcomings may have heightened his compulsion to charm.

Viewed through today’s lens, Cohen’s busy love life would be interpreted differently. As an author Posner makes no moral judgement (he’s helped by the book’s format of direct quotations, a distancing device that in the main leaves the reader to decide).

But one instance that occurred two years before 1967’s Summer of Love seems to encapsulate the prevailing attitude of the time. Anne Coleman, a Canadian writer and college friend, remembers Cohen approaching her at a party in 1965 and intently stroking her stomach before carrying on his prior conversation. “It was one of those 1960s moments – so typical of a party at that time. Nowadays it might be seen as sexual harassment. It certainly wasn’t.

“There wasn’t anything about Leonard,” she added, “that seemed as through he would be doing something that wasn’t welcome. It was a sensual appreciation.”

Cohen’s long on-off relationship with Marianne Ihlen is a major focus of the book. She was the subject of So Long, Marianne, one of his best-loved songs, and several others too. Largely played out on the Greek island of Hydra, a beatnik idyll, their relationship was passionate and deeply felt. Cohen first heard about Hydra in London from banker Jacob Rothschild, whose mother was living there at the time. He visited in 1960 and fell in love with the place. It was, he said, “as if everyone was young and beautiful and full of talent – covered in a kind of gold dust”. It was also where he met and fell for the Norwegian Ihlen, who had a young son Axel. But Cohen and Ihlen’s relationship was at times as toxic as the partner-swapping and backbiting that went on under the shimmering Aegean sun.

Model Madeleine Lerch recalls visiting Hydra in 1961. “I don’t know if [Cohen] and Marianne had broken up, but there were tons of other women in his life,” she says. “Everyone was sleeping with everyone else. Open marriages. It really was a painful, emotionally dangerous time,” says Aviva Layton, a friend of Cohen’s.

Posner’s book raises two questions that cast a potentially unsavoury light on the relationship. Again, given the book’s oral-history format, there is no vouching for the accuracy of people’s recollections. First, some friends suggest that Cohen gave Ihlen’s son Axel the drug LSD. The author suggests it’s “extremely unlikely” that this happened but it does give an insight into the freewheeling hedonism of the time.

The second question relates to abortions. Five acquaintances of Cohen say in the book that Ihlen, who also died in 2016, underwent numerous abortions because Cohen didn’t want children. This chimes with information suggested by filmmaker Nick Broomfield, with whom Ihlen had a relationship, in last year’s documentary Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love. “She knew Leonard did not want to have kids, and she did not want to burden him,” says Layton.

Away from Ihlen, there were affairs aplenty. Cohen had double standards when it came to fidelity: it was fine for him but not for his partners. One of Cohen’s girlfriends when he was with Ihlen was Wendy Patten Keys. She says that Cohen was “mad” at her because she was not faithful to him when he was off in Greece. He wrote a poem called Why I Happen To Be Free that Patten Keys believes is about her. “Forsaking the lovely girl / Was not my idea / But she fell asleep in somebody’s bed,” Cohen wrote. Life was emotionally traumatic for his lovers. “I constantly felt I was sharing him,” says Patten Keys.

In any case, Cohen and Ihlen’s relationship faded as the 1960s drew to a close. “Love seeded on Hydra is, by definition, doomed,” explains Cohen’s friend Barrie Wexler. In July 1967, Cohen met Joni Mitchell at the Newport Folk Festival where they were both performing. They had a relationship that lasted almost a year.

Mitchell was later dismissive of him. “I briefly liked Leonard Cohen, though once I read Camus and Lorca I started to realise that he had taken a lot of lines from those books, which was disappointing to me,” she said. Also in 1967 – although some accounts put it at 1968 – Cohen met Janis Joplin in the lift of New York’s Chelsea Hotel. She said she was looking for Kris Kristofferson. Cohen replied: “Little lady, you’re in luck, I am Kris Kristofferson.”

They spent the night together, with Cohen going on to write Chelsea Hotel #2 about the encounter. "I remember you well in the Chelsea Hotel / You were talking so brave and so sweet / Giving me head on the unmade bed / While the limousines wait in the street,” he sang. Again, Joplin was later less than complimentary about their encounter.

There were a few romantic non-starters too. Cohen became obsessed with singer Nico, a disciple of Andy Warhol and occasional member of the Velvet Underground. But she rejected him. Cohen called Nico the “Marlene Dietrich of nihilistic rock”, while Warhol called Cohen’s first album “Nico with whiskers”. She is thought to be the inspiration behind at least two Cohen songs, Take This Longing and Joan of Arc. And there is a long passage in the book by an artist called Barbara Dodge, who claims that Cohen tried at length to seduce her upstairs in his mother’s house when she was 17 or 18 (and still a virgin). The encounter was later mentioned in Cohen’s poem, The Energy of Slaves.

What we see in Posner’s book is Cohen as an almost otherworldly magus who lived, as he himself put it, “on seaweed and amphetamines”. His allure was (almost) total. He lived in perpetual motion; a life of constant searching. It was this quest that took his life from Judaism to Scientology and Zen Buddhism; it was this quest that took him from poetry to novels to music; and it was this quest that took him from bed to bed to bed.

Everything about Cohen’s aura and era is neatly summed up in one short anecdote in the book. Jacquie Bellon, a friend of the singer and the first wife of American writer Steve Sanfield, tells Posner that Cohen stayed with her and Sanfield in Santa Barbara in 1967 or 1968 when they were boyfriend and girlfriend. Nothing happened between Cohen and Bellon, although she tells the author there was “definitely mutual attraction”.

Bellon makes what’s almost a passing comment. But the throwaway detail speaks volumes about this unlikely lothario’s lasting effect on women. “When [Cohen] left, he left behind a black Italian designer turtleneck. I still have it. It’s very small.”

Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years by Michael Posner is published by Simon & Schuster on November 26