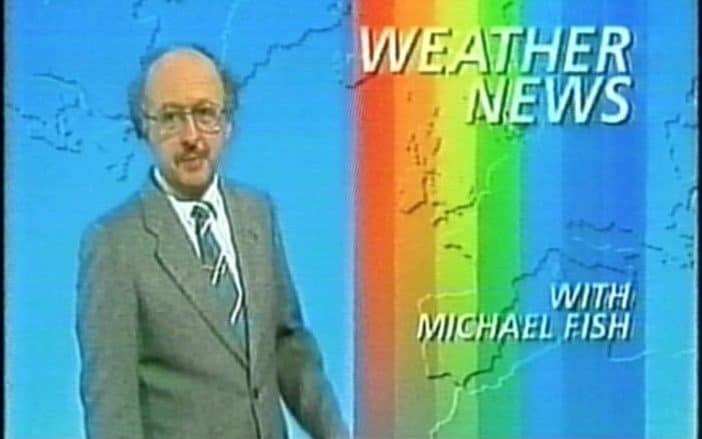

Weatherman Michael Fish on missing the Great Storm of 1987: 'when I saw what happened I thought, 'oh s***'

“Earlier on today apparently a woman rang the BBC and said she had heard a hurricane was on the way.” So began the most infamous weather bulletin in British history on the lunchtime news 30 years ago. “Well I can assure people watching,” smirked weather forecaster Michael Fish, “don’t worry, there isn’t.”

Just a few hours following that fateful broadcast in the early hours of October 16, 1987, the south coast of England was battered by the greatest storm witnessed in nearly three centuries. Gales reaching 115mph caused utter devastation across the southern half of the country, leaving 18 people dead, 15 million trees flattened, and a repair bill totalling £2bn.

For Fish – a previously benign national presence in chequered two-piece suits of varying shades of beige - the Great Storm led to him being lampooned in the press. Not as a harbinger of doom, but rather somebody who failed to see it galloping across the Channel towards us.

Three decades on and the 73-year-old Fish is unrepentant. “We didn’t [technically] get a hurricane so in a way I was correct,” he says. “Even though it did end up sounding a bit stupid.”

Fish, who is married with two children and two grandchildren, insists the storm is an unfair stain on his reputation. After all, he continued to work for the Met Office until retiring in 2004 (following 42 years loyal service) and was appointed MBE that same year. The BBC wanted him to work even longer, he says, but Civil Service rules decreed he must retire at 60.

Nowadays, the weatherman seems to secretly revel in the notoriety – a clip of the fateful broadcast was, to his great delight, used in the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympic Games. But at the same time he is eager to clear his name - and shift the blame.

It was his colleague Bill Giles, Fish points out, who was on duty the evening before the storm struck and also failed to properly forecast the storm. “His forecast said it would be a little bit breezy up the Channel which is something of an underestimate but for some reason the press never latched on to that,” he says.

Such grumbles aside, Fish insists both were mere conduits for mistakes made far higher up the chain of command. The real villain of the piece was the Met Office computer (and the senior forecaster who interprets the data).

“In a way it was a bit unfair and unfortunate,” he says. “You shouldn’t really target the messenger. The thing that should have been criticised was the computer at Met Office HQ. It was that which got the forecast wrong and Bill Giles and I were just purely the mouthpieces. We had no input whatsoever into the computer or anyway of arguing with it. We just had to say what it said.”

The storm prompted the launch of a public inquiry, as well as an internal Met Office investigation into why forecasters (both human and artificial) missed it so badly. Rather than barrelling in over the Atlantic to the west as most of our storms do, the 1987 squall formed in the Bay of Biscay to the south. It proved so deadly because of a so-called “sting jet” at the rear of the weather front – a hook-shaped airstream not recognised in Fish’s time but which forecasters now know to provoke severe gusts of wind.

The Met Office computer on which Fish and his colleagues relied in 1987 made four million calculations a second. Nowadays it is capable of 14,000 trillion calculations a second. Most of these come from satellites which were rarely used 30 years ago.

As a direct result of the Great Storm, deep ocean weather buoys were located around the British Isles to provide hourly weather information and help us to monitor developing weather conditions. Where grid squares of 150km were once used for weather prediction, now the range is 10km.

In order to demonstrate these advances, today the Met Office announced that it had rerun the conditions in 1987 to determine whether its new supercomputer would have made the correct forecast and proudly claimed it spotted the weather system forming up to a week ahead.

Fish’s own recollections of the storm are remarkably anodyne, considering the destruction it wrought across the country.

On October 16 he woke up at around 3am and stepped out into the garden of his West London home but despite the blustery conditions he insists that he noticed nothing particularly out of the ordinary (at that time in the morning 94mph gusts were recorded elsewhere in London). His drive into the BBC was along an urban dual carriageway and he says he did not notice any trees felled.

In an era before mobile phones the storm had bought down so many electricity and telephone cables that it took a long time for the severity to become apparent.

“I had no idea of the devastation,” he says. “It took some time for the true facts to really emerge.”

And what, I wonder, did he think when he realised the scale of the disaster? Fish pauses for a moment to consider: “Oh s***,” he recalls.

October 16, 1987, was a Friday and with the Met Office spokespeople off that weekend Fish says he was left to the mercy of the mob. His house was besieged by hundreds of reporters and he was forced to go to ground.

“I regret that, being a junior civil servant, we weren’t supposed to talk to the press and I regret that I wasn’t able to stand up and clarify the situation and give them the true facts rather than letting them go away and make up rather strange stories,” he says. “In the end I decided not to read them.”

Despite his monstering in the press Fish insists the BBC never received a single complaint about his broadcast. “I got lots of letters from the general public at the time and they were almost entirely supportive,” he says.

However battered he may have been by the experience of 1987, the unpredictability of Britain’s weather remains a source of great delight to him. Nowadays Fish remains involved in forecasting, contributing to the online service Netweather.TV. He also lectures around the country, particularly on the perils of climate change, in talks entitled: The ultimate weapon of mass destruction.

“Millions have died already as a result of global warming and millions are going to die in the future,” he says. “Even if we do decide to do something about it, it’s too late as far as many places and people are concerned. I think it’s absolutely horrendous.”

He calls Donald Trump’s decision to pull out of the Paris Climate Agreement, “bloody daft”. “Perhaps I should become a politician and start stirring things up a bit?” he ruminates, not entirely joking.

Even if we may now be able to better predict the arrival of turbulent weather, Fish warns we should not rest on our laurels. Nature is growing in ferocity, too.

And when does he think the next big storm might hit? “I would make an absolute fortune if I knew that,” he says.

The old weatherman hasn’t done badly out of failing to predict the last one, after all.