'I wanted to be a living work of art': why Jordan is the queen of punk rock style

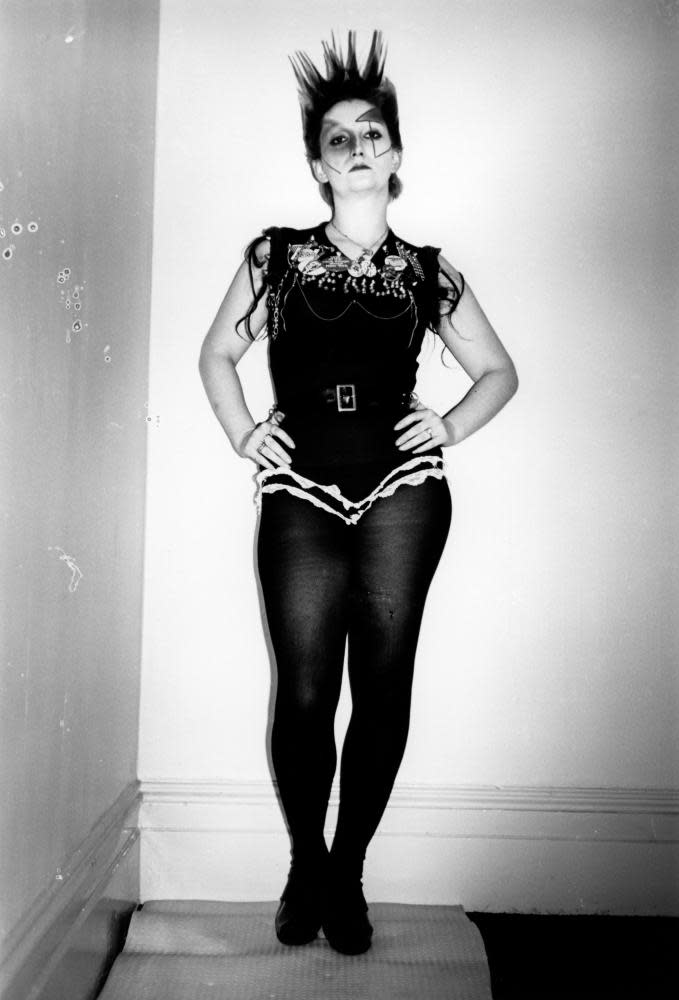

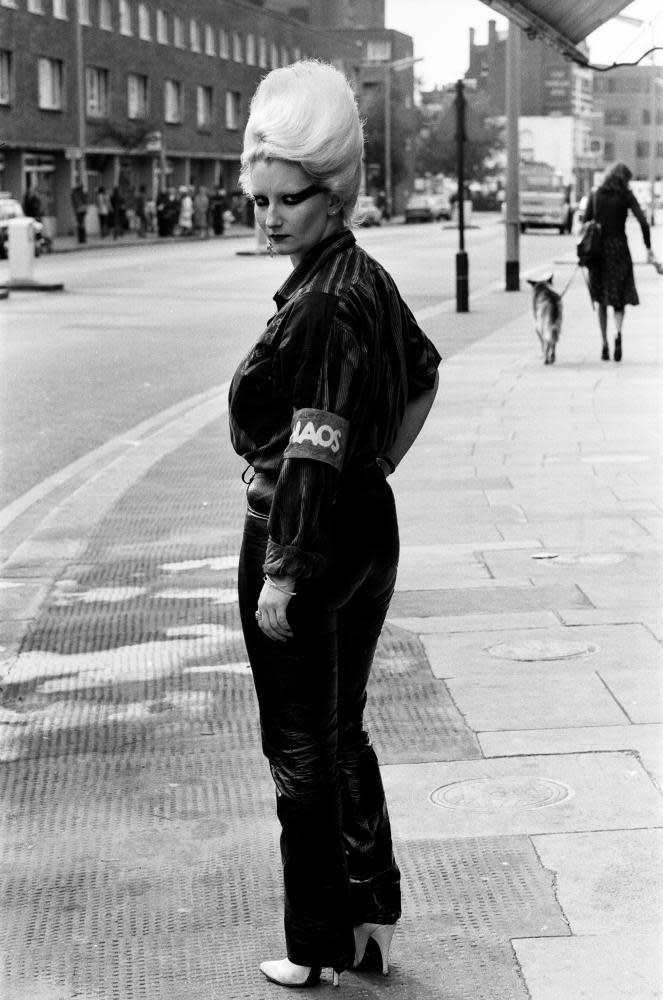

Introducing Jordan – AKA Pamela Rooke – in his 1991 punk history England’s Dreaming, Jon Savage describes her life as “a pas de deux with outrage”. This was due to “an appearance so startling that, every time she stepped out the door, she put herself on the line”. See PVC, fishnets, rubber, XXXXL beehives, suspenders, casual nudity (she quite often wore nothing from the waist down, or no top under a mohair sweater) and a curled lip. No wonder Jordan (a name Rooke took, somewhat incongruously, from the golfer Jordan Baker in The Great Gatsby) became the poster girl for a movement. Savage goes as far as to declare her the first Sex Pistol, while Adam Ant said she invented punk rock.

A new generation will discover the sheer subversion of Jordan with Danny Boyle’s new series, Pistol, which tells the story of the band and the assembly cast of characters around them, including Jordan, who worked at Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s shop, Sex, on King’s Road in London. Images of Maisie Williams as the punk idol have been seen this week and have the outrage and scandal that you might expect. Williams wears stockings, suspenders, a see-through mac and the kind of eyeliner visible from space.

What remains jaw-dropping about Jordan is that she wore these clothes in the most mundane of circumstances. She styled her hair in a red mohican at the age of 17, outraging teachers at her school, and prompting her mother to walk ahead of her when they were out on the street. Based in her home town, Seaford, East Sussex, while working in Sex, she would commute in these outfits – making her train journey almost a kind of performance art. “Some of the things I wore were quite near the knuckle,” she said in an interview with the Guardian in 2019. “People were apoplectic with rage. I had to be moved into first class for my own safety.” Jordan purposefully stood out against the backdrop of 70s Britain – an era she described as “a grey and beige and taupe time”.

Jordan, improbably, worked at Harrods before being recruited by Westwood and McLaren – and did so while wearing green lipstick. She first appeared in Sex at the age of 19 wearing gold stilettos, and a 50s-style outfit of net circle skirt and a bullet bra, but without anything over the top. She became perhaps the most notorious shop girl in history, a sort of high priestess of retail, who would discourage people from buying the wares. “I wasn’t prepared to sell things that looked awful on people just because they had the money to buy it,” she said to Dazed magazine in 2016. “It would have been bastardising something beautiful just for the money.” A young Boy George was in awe of her. “She dressed like a modern Tiller girl, carried a whip and hissed at customers,” he wrote in his 1995 autobiography Take It Like a Man. “Hers was a very modern sales technique.”

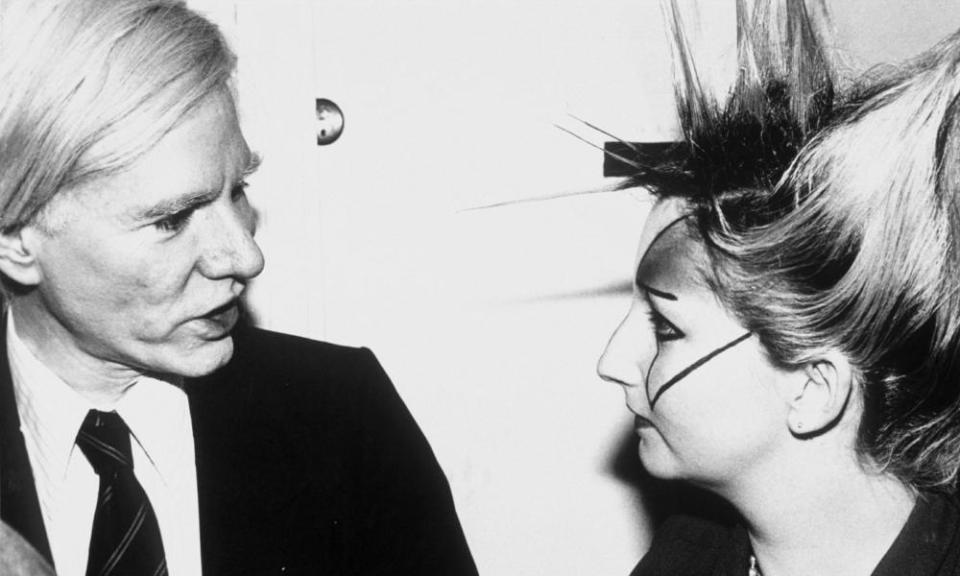

McLaren embraced Jordan’s visual anarchy and recruited her as a kind of Bez of the Pistols; she appeared on stage with them at gigs. She was photographed by Andy Warhol (and with him, at the ICA in 1977) and starred in Derek Jarman’s Jubilee. The film director tracked her down to play the history-mad Amyl Nitrate after seeing her from afar in Victoria station. Her performance in the film, singing Rule, Britannia! in a union jack tunic, DayGlo makeup, metal helmet and trident, was anything but taupe. It was a sort of inverse of Boudicca, out to shock the establishment by sending up its own imagery.

Her pushing of boundaries included times she utilised imagery that is widely (and rightly) seen as repellent. See the swastika, worn on the armband of a T-shirt, which she refused to take off for a TV appearance with the Sex Pistols in 1976 (it was covered with sticky tape in the end). “I’ve always seen it as … a desensitisation of the swastika as an emblem,” she said to Dazed. “It should be remembered that there was Karl Marx on one side and the swastika on the other.”

A 1977 profile in the NME roasts Jordan for her “obsession with fashion”, suggesting that her outfits would ensure she was never attractive to men. “Underneath the thick black lines and heavily rouged cheeks there might well be a stunning female trying to get out,” it reads. “It’s so hard to tell my dears, for Jordan does such a good job of covering up any good features she may possess.”

In 2019, she told the Daily Mail: “I wasn’t being brave or an exhibitionist. I didn’t care what anyone thought, I wanted to be a living work of art.” This refusal to conform to the conventions of female appearance perhaps meant that Jordan was more radical than any male punk – because women’s appearance was (and still is) so much more scrutinised. “Men were confused by me,” she said to the Guardian. “They would wolf-whistle, shout all kinds of things, even offer me money because they didn’t understand why I looked like I did.” Despite the fact that Jordan now has settled down somewhat – she works at a vet, breeds burmese cats and sold her collection of punk pieces in 2015 – her impact on fashion remains a pas de deux with outrage more than 40 years after she made her last commute from Seaford.