Want to Know What Really Went Down Between Quint and Hooper on ‘Jaws’?

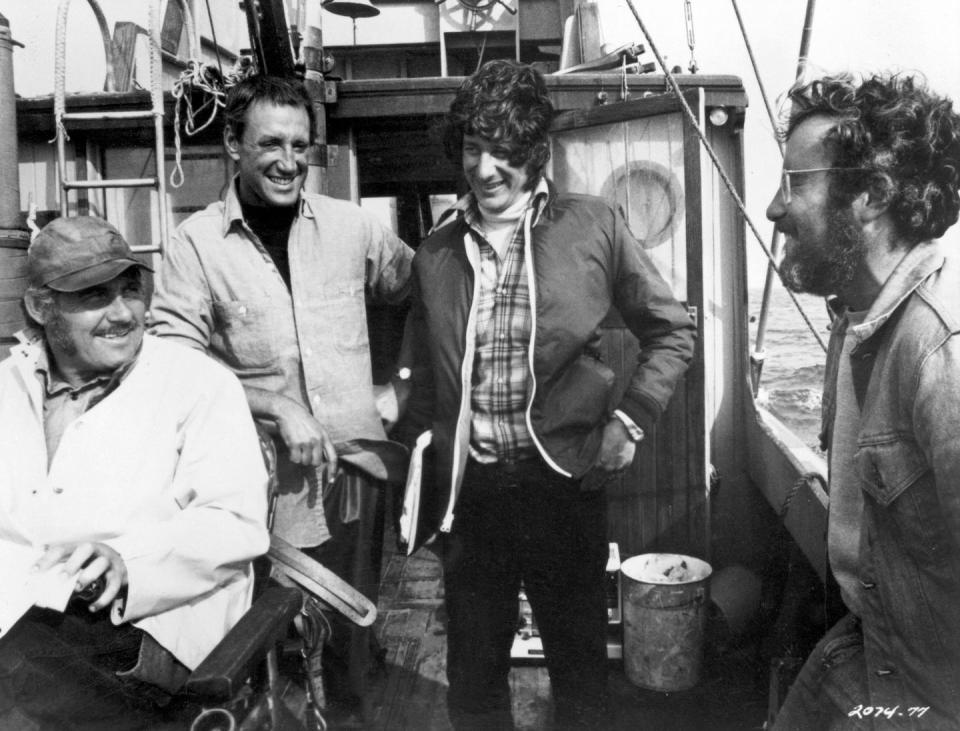

Ian Shaw was a small boy when he went to visit his father, Robert, on Martha’s Vineyard, where the revered British actor was making a movie about a great white shark that terrorises a New England town. Or rather, not on Martha’s Vineyard so much as off it, as the film’s 26-year-old director, Steven Spielberg, wanted to capture the dark tempestuous essence of the ocean by shooting on the ocean itself. Shaw was playing Quint, a gleaming-eyed, Ahabian fisherman who accepts a bounty to kill the monster, alongside Hollywood stalwart Roy Scheider as Brody, Amity Island’s besieged the chief of police, and a promising New York upstart, Richard Dreyfuss, cast as the young know-it-all marine biologist, Hooper.

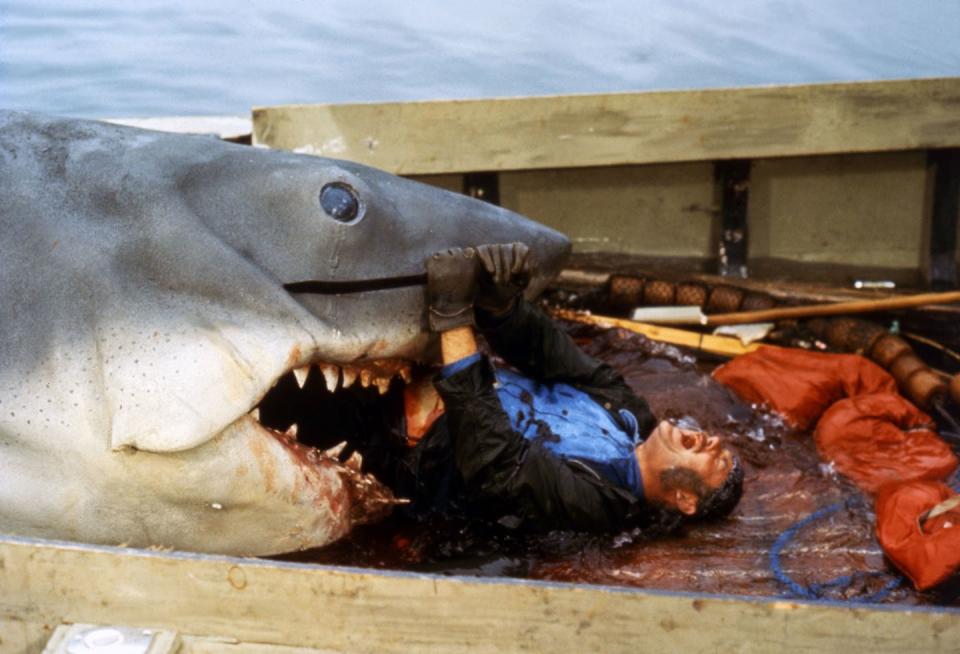

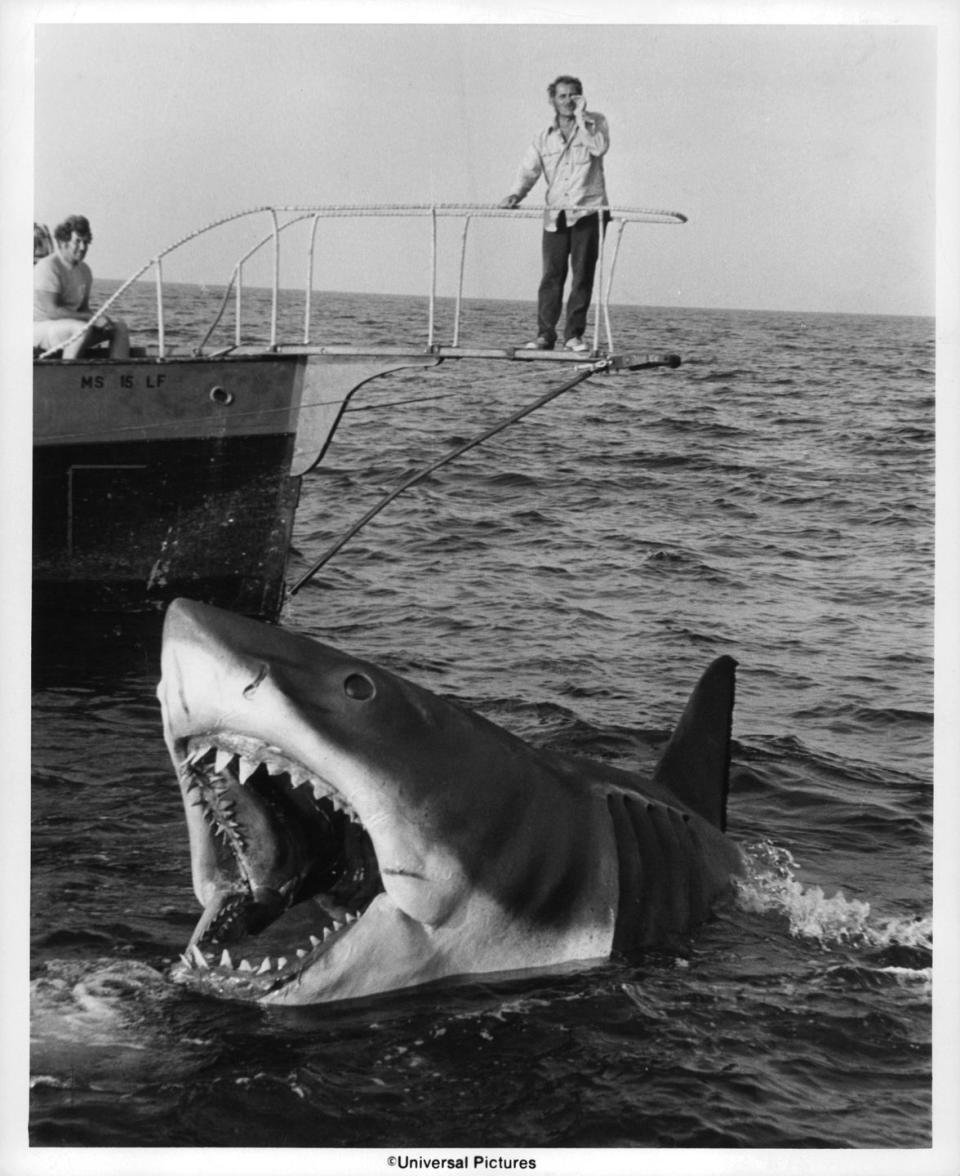

The story of the making – or, for much of the time, the not-making – of Jaws has gone down in cinematic lore. Shooting on the Atlantic meant that the production was at the mercy of the weather and also the salt water, which played havoc with the pneumatic components of the mechanical shark – nicknamed “Bruce” after Spielberg’s lawyer, Bruce Raynor. As a result, the budget was spectacularly blown and the cast and crew had a lot of time to kill; or, in the case of Shaw and Dreyfuss, who had a famously turbulent relationship, nearly kill each other. But of course the problems of Jaws also necessitated the movie’s innovations: the malfunctioning fake shark meant that in order to create suspense, Spielberg deployed John Williams’ score and underwater shots from the shark’s point of view, both of which are, today, iconic.

And now, it has led to another innovative creation. The Shark is Broken is a play, co-written by Ian Shaw, who is now a few years older than his father was when he shot Jaws, and the British comedy writer Joseph Nixon. It centres on the film’s three main actors as they wait around to shoot (“waiting” of course, being a classic dramatic trope: see also, of course, Godot, Sartre’s Huis Clos, and, as name-checked in this one, Pinter’s The Dumb Waiter); the result is both a funny and touching study of the dynamic of the three men, and a paean to the much-loved film. After a sell-out Edinburgh run, an extended version of the play is just opening in London’s West End, starring the original cast of Demetri Goritsas as Roy Scheider, Liam Murray Scott as Richard Dreyfuss, and, in a turn that is both poignant and, at times, freakishly uncanny (at the preview we saw, there was an audible murmur when he first appears on stage), co-writer Shaw as his father, Robert. Esquire caught up with the cast ahead of opening night.

ESQUIRE: Ian, is it right that the idea for The Shark Is Broken started with a moustache you’d grown for another role?

IAN SHAW: Partly. My family always said, “You look like your dad,” so it's been a constant thing, but I looked in the mirror and thought: “That's ridiculous. I do look like Quint now.” I'd hit a certain age. But it was several little things percolating. I had read The Jaws Log [the legendary behind-the-scenes account written by the movie’s co-writer Carl Gottlieb] quite a while ago, which I found absolutely fascinating, because I hadn't realised the full extent of Dreyfuss and Shaw's difficulties together. And then also, I loved Jaws. It’s silly to say isn’t it, because I’m the son of Robert Shaw, but I think even if it had had a different actor in it, it would still have been one of my favourite films.

How did the play take shape?

IAN SHAW: I wrote down a few ideas, but then I felt sort of ashamed of myself, because I thought this was going into potentially embarrassing territory for my family. It wasn't until I probably had a beer too many and mentioned it to a few of my friends that they said, “No, you should do something with this.” Even when we were writing it, Joseph Nixon and I didn’t know where it was going.

The play centres on the sometimes combustible dynamic between the three lead actors while they were stuck on the boat waiting to film. Was that triangulation of characters fun to explore?

LIAM MURRAY SCOTT: Yes, because it’s just as it is in life when you get three completely different people together: there are so many different tactics you’ve got to use to manage personalities. Dreyfuss and Scheider’s relationship is quite amicable, but the second you throw Shaw in there…

IAN SHAW: I think to some extent Roy is their audience. They show off in front of Roy.

LIAM MURRAY SCOTT: He’s very much the mediator, the dampener on their personalities. He keeps them in check.

IAN SHAW: If it wasn’t for Roy they would have killed each other.

DEMETRI GORITSAS: It registered to us when we were rehearsing that, just as Covid made everyone house-bound, these guys are ship-bound. During Covid, you’d start your day and think things were going to happen, which would then become these very long circuitous affairs, or never happen. That’s a bit like what these guys go through with the filming. They’re in a kind of lockdown.

Ian, did you always want the play to be funny?

IAN SHAW: I like to see things that are funny and, hopefully, deal with more difficult emotions as well. I like to laugh. And also people sometimes forget, if they haven’t seen it for a while, just how funny Jaws itself is. When Hooper’s about to go in the shark cage and Quint sings as though he’s going to die, or Dreyfuss arguing with the mayor in front of the sign… There are so many nice bits of humour in the film.

Demetri and Liam, when did you first see Jaws?

DEMETRI GORITSAS: I confess I did not sit down and watch Jaws all the way through until the night before the audition. But my compliment to it is that I realised how much of it I had seen, all the references from it that are embedded in popular culture.

LIAM MURRAY SCOTT: I watched Jaws for my A-level film studies. It was like reading Of Mice and Men or The Great Gatsby for GCSE English when you’re a teenager: “These are just old books I don’t care about.” But going back to them it’s like, “No, this is a masterpiece.”

Ian, your introduction to it was obviously a bit different. What do you remember of visiting your father on location in Martha’s Vineyard?

IAN SHAW: I remember swimming and playing on the beach. And I went into where they kept the sharks and they showed me Bruce, the great white, which I found quite scary. I saw the film while my dad was still alive [Robert Shaw died in 1978, aged 51], on a small screen, like an editing suite. I would have been seven or eight, and I had nightmares. I remember I cried out for him, because I thought there were sharks swimming around my bed, and so he came to save me. I knew he wasn’t really eaten in the film. I knew he was acting.

Yet sharks have haunted your subconscious ever since!

IAN SHAW: The film made me terrified to go in the swimming pool for two years. There’s not much logic to that. I’m probably still a little nervous. I think for me the worst shot is the underneath, you know, when you’re seeing people's legs swimming? They just look so vulnerable. That always stayed in my mind. When I’m in the water and I can’t see below I’m always thinking “Wuhhhh….”

Were you in any way aware of the troubles the production was going through?

IAN SHAW: Not at all. I thought, and for many years afterwards actually, that Richard and Roy and Robert were best friends. The first time I really thought there was an issue was auditioning for Richard. He was directing Hamlet at the Birmingham Rep and when I mentioned who I was he took a turn for the worse. I remember James Earl Jones did a pirate film with my dad [the 1976 adventure movie, Swashbuckler], and I went to see him do Fences on Broadway. I very nervously went backstage to see him and he gave me the biggest hug ever. I was kind of expecting that from Richard. I didn’t get one.

Liam, Richard Dreyfuss is the only one of the three actors still alive. Does that affect how you play him?

LIAM MURRAY SCOTT: Not in the sense that I feel like I’m not doing him justice, but it’s a lot of pressure to live up to. Also in the play he’s the brash upstart, this abrasive character rubbing up against two seasoned actors. There is a bit of a worry of making him dislikeable, which I want to avoid at all cost, and I hope I’ve achieved. There were rumours he wants to come on opening night. He knows the play is happening.

If he comes to see it would you want to know?

LIAM MURRAY SCOTT: Absolutely not! Do not tell me who’s in the audience. There was a night in the Edinburgh run where Steve Coogan asked to come. We all knew he was in the audience, and every so often you’d be in the middle of a scene and think, “Oh, Steve Coogan’s out there somewhere…. Oh hang on, I need to do this show.”

The play touches upon Dreyfuss’s cocaine use, which would become a problem in later life, and also Shaw’s alcoholism, which was already full-blown. Ian, were you interested in exploring that?

IAN SHAW: I think Dreyfuss's addictions and Shaw's addictions were symptoms of their personality: crutches that people use who are not entirely stable. Although I think Shaw's alcoholism is slightly more complex, because he comes from a group of men who, perhaps even subconsciously, felt that acting was not masculine enough. Testing yourself in the pub, being able to outdrink everybody and still be standing was somehow vital proof that you were a real man. Obviously acting can be very silly – you can find yourself in extraordinary costumes at times – but I feel that our generation has a different kind of masculinity. Thank god.

Has acting as your father made you see him differently?

IAN SHAW: It’s very hard to describe, but when you’re walking in his shoes you feel a kinship. My sister sent me his diary recently, which hasn’t strictly speaking gone into the play but has informed the alcoholic arc of the piece. It was quite a personal drinking diary, marking down that he’s had a dry day, and then maybe he’s had a lapse, and how he feels about that. I felt a great deal of sympathy for him, because he was really trying to battle with something. It’s a very moving struggle.

The play features scenes set around the filming of his famous “Indianapolis” speech. How does it feel to perform that?

IAN SHAW: The first time I did it, utterly terrifying. I love that speech. I’ve always loved it. It’s also so theatrical: it goes against the rules of cinema to talk for that long; you tend to show the action, even if it's a flashback or something. But I think it works really well in a theatre.

Have you found the show attracting a lot of Jaws super-fans?

LIAM MURRAY SCOTT: There’s a balance. I think initially people say, “Ooh, it’s a play about Jaws! Amazing! I loved Jaws!” But then you come away with so much more. There’s so much deeper below the surface.

Do you think it might have a life after the West End? Broadway perhaps?

IAN SHAW: I’m crossing everything. I hope that we get good reviews and that it does have a life outside London, absolutely.

DEMETRI GORITSAS: We’re thinking on the Atlantic Ocean somewhere.

IAN SHAW: Somewhere off the coast of Cornwall.

LIAM MURRAY SCOTT: With the audience on a flotilla.

'The Shark is Broken' is at the Ambassadors Theatre in London until 15 January 2022 thesharkisbroken.com

You Might Also Like