Tweet of the Week: the starling

The return of winter over the past week has at least brought one benefit – a final chance to see the last great starling murmurations of the season.

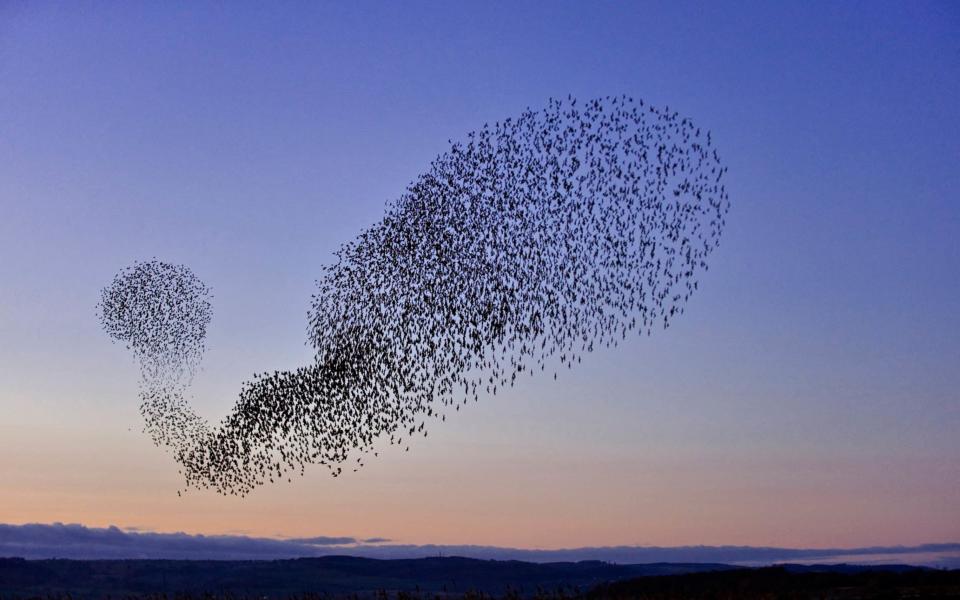

For the uninitiated, this is one of Britain’s most arresting natural spectacles: at dusk thousands, sometimes hundreds of thousands, of the birds gather in flocks to perform mass aerial acrobatics.

They sweep about the sinking sky like a shoal of herring, assuming all manner of unexpected shapes before eventually spiralling downwards to roost for the night.

You can stumble across a murmuration anywhere: seaside piers (Brighton and Aberystwyth are particularly renowned), reed beds, power stations and farmland. I was lucky enough to drive past a flock last weekend, swirling over an otherwise unremarkable stubble field on the edge of Leeds.

The amassed starlings are hypnotic to watch and made all the more splendid by the fact that ornithologists still don’t quite know why they do it. Protection, perhaps? Warmth? Or simply a group chatter before heading off to bed?

Individually, the starling makes a splendid bird. Black from a distance, up close its plumage is an iridescent purple and green. Its breast is speckled like the night sky.

The starling is not especially big, but pugnacious all the same: more than willing to scrap for titbits dropped in city centres and renowned for the speed at which it can clean out a bird feeder.

Its call is a harsh, electric squeak with endless possibilities, as the starling is adept at mimicking other birds. In Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part I, Hotspur fantasises about teaching a starling to say “Mortimer” (one of the king’s enemies) and giving the monarch the bird as a gift.

Sadly, these murmurations are becoming an increasingly rare sight. In Britain the starling population has fallen by 80 per cent in the past 30 years or so. The loss of suitable roosting sights is deemed a factor, so too the decline of invertebrates such as crane fly and leatherjackets upon which the birds like to feed.

For now they still swirl like nature’s lava lamp, but there is a precariousness in the patterns they weave.