The true story of the girl who was a 'gift' to Queen Victoria

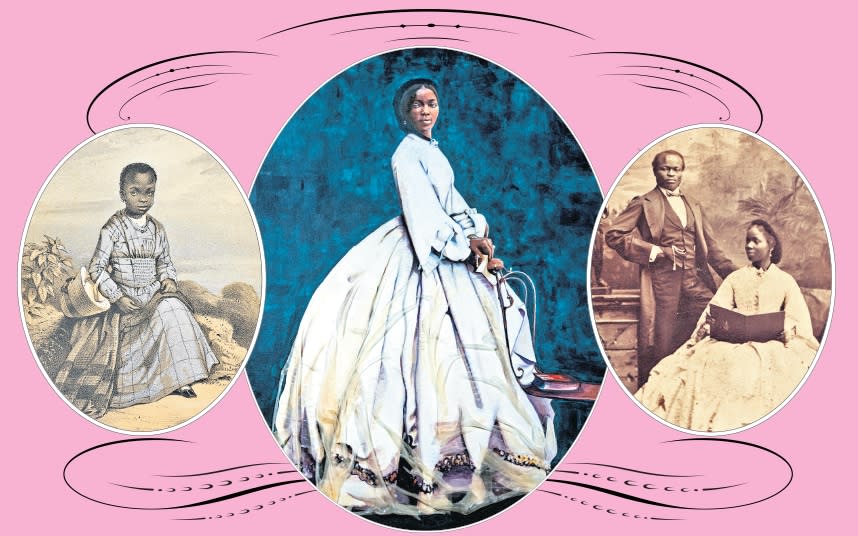

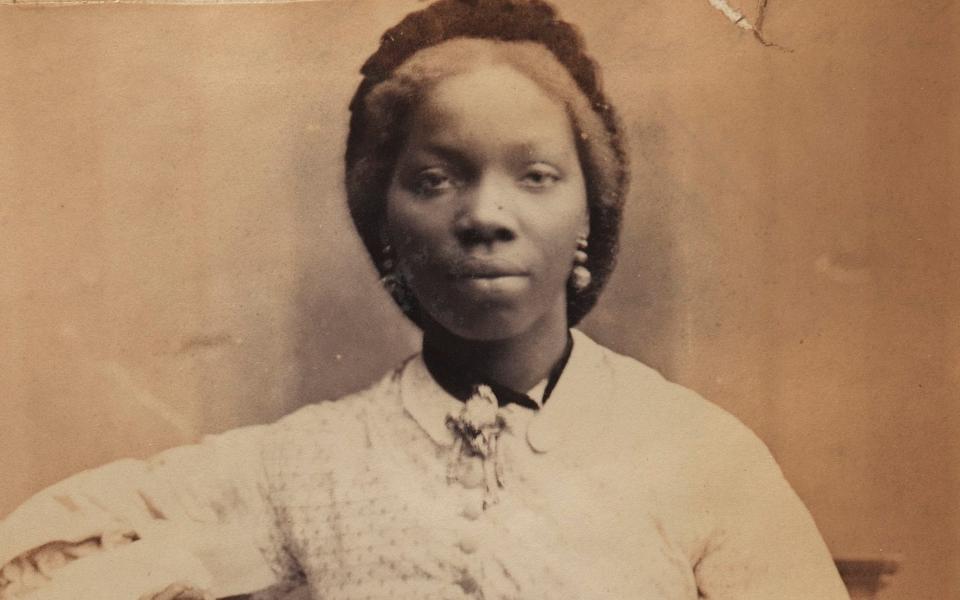

A new and specially commissioned portrait of Sarah Forbes Bonetta, a captive African princess “gifted” to Queen Victoria, has just been unveiled at the monarch’s seaside home, Osborne House, by artist Hannah Uzor, as part of a drive by English Heritage to highlight black figures “whose stories have been previously overlooked”. It is a worthy aim, but there is much of Sarah’s story still to be uncovered.

Sarah was never, as is frequently stated, the Queen’s official god-daughter (that honour was given later, to Sarah’s daughter), though the beginning of her life was marked by tragedy.

A chieftain’s daughter from the Egbado Omoba tribe of what is now Ogun State in Nigeria, she was captured in a raid by a rival tribe from the nearby West African kingdom of Dahomey – today’s Benin. She was rescued not long after by a British naval officer, Commander Frederick Forbes, who had been sent on a mission of gunboat diplomacy to induce King Guezo of Dahomey, who had built his wealth on the slave trade, to abandon the practice.

Guezo was said by Forbes to have countless wives, a personal bodyguard of female Amazons and a penchant for ceremonial human sacrifice, which he often laid on for visiting foreigners. Horrified to discover that the king was about to sacrifice this little girl in his honour, Forbes persuaded him to spare her by flattering him that she would be the perfect gift “from a Black King to a White Queen”. On the journey to England, she was baptised Sarah and given the name of Captain Forbes and his ship, HMS Bonetta; it was subsequently learnt that her West African name was Aina.

The white aristocracy looked upon this “Dahoman captive” as little more than an exotic colonial curiosity. Queen Victoria, however, showed genuine affection for her, calling her Sally, and becoming a loyal friend and protector. Sarah first visited her at Windsor in November 1850, when she impressed her by being “sharp & intelligent”, inspiring Victoria to pay for her upkeep.

A new portrait of Sarah Forbes Bonetta, the daughter of an African ruler who after meeting Queen Victoria became officially attached to the royal household, will go on display at @EHOsborneHouse throughout October. 🎨 Painting by artist Hannah Uzor. pic.twitter.com/bhIGIQc1Zt

— English Heritage (@EnglishHeritage) October 7, 2020

While plans were made for Sarah’s future she lived very happily with the Forbes family at Winkfield, five miles from Windsor. “She is a perfect genius,” remarked Forbes, “far in advance of any white child of her age, in aptness of learning, and strength of mind and affection.”

Sarah visited the Queen at Windsor on several occasions, becoming particularly attached to her second daughter, Princess Alice. But when, within a few months of her arrival, she developed a persistent cough, Victoria became concerned that the damp English climate was bad for her health. In May 1851 she agreed that Sarah be sent to a missionary school in Sierra Leone where the daughters of better-off African businessmen were educated to be “English ladies”.

Here, Sarah quickly became a star pupil, but begged to be brought back to England. In September 1855 the Queen commanded her return and recorded in her journal: “Saw Sally Forbes, the negro girl whom I have had educated: she is immensely grown and has a lovely figure.”

Sarah lived a relatively comfortable life for a while with the Rev James Frederick Schön, his wife Elizabeth and their children, at Palm House in Gillingham, Kent, where you can see a plaque commemorating her time there. In January 1858, as a mark of the high regard in which Victoria held her now 15-year-old protégée, the British press reported that “The African Princess” had been invited to attend the wedding of her eldest daughter, Victoria the Princess Royal.

Ultimately, Sarah suffered the same fate as that of the Queen’s daughters. At 18, Victoria’s thoughts turned to seeing her suitably married – to someone of her own race. In November 1860 she had already rejected the proposal of a former navy officer and wealthy Yoruba businessman, Mr James Davies, a widower 15 years her elder. Two years later, Queen Victoria pressed her to accept. Sarah resisted as hard as she could – writing to her “dearest mama” Mrs Schön of her “state of mental misery and indecision… I do not feel a particle of love for him and never have done so” – but in the end, had no option but to submit. Queen Victoria commissioned her favourite court photographer, Camille Silvy to take the couple’s engagement portraits for her own personal photograph albums.

The marriage was conducted by the Bishop of Sierra Leone at St Nicholas Church in Brighton on August 14 1862 and caused something of a stir. Sarah’s bridal gown was paid for by Queen Victoria and she had 16 bridesmaids of whom four were black. British newspapers were full of deeply condescending accounts, describing the “grand field-day” as an edifying example of white benevolence and the “progress of civilisation caused by the influence of Christianity on the negro”. It was, said the Windsor and Eton Express, proof of what can be achieved by “those of the African race who have proved themselves capable of appreciating the advantages of a liberal education”.

Soon afterwards, Sarah and her husband sailed for Africa, settling in Freetown, then Lagos, where her first child, born in 1863, was named in Victoria’s honour. The Queen agreed to be godmother, presenting the baby with a gold cup and salver inscribed, “To Victoria Davies, from her godmother, Victoria, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, 1863.” Arthur followed in 1871 and Stella in 1873.

In December 1867, during a visit to England, Sarah saw the Queen for what would be the last time. Victoria again recorded the event: “Saw Sally, now Mrs. Davies & her dear little child, far blacker than herself, called Victoria & aged 4, a lively intelligent child, with big melancholy eyes.”

Sarah was, however, now sick with tuberculosis and went to Madeira for her health, where she died on August 24 1880 at the age of 37. The Queen heard the news on the very day she was expecting a visit from her god-daughter Victoria, later resolving in her journal, “I shall give her an annuity”.

True to her word, the Queen paid for her education at Cheltenham Ladies’ College before she returned to Africa. In November 1900, only two months before the Queen’s death, Victoria visited her with her own two children, and was warmly greeted with kisses and hugs, tea and gifts. Her daughter was named after Queen Victoria’s youngest daughter, Princess Beatrice of Battenberg, who followed in her mother’s footsteps and became godmother to Beatrice, whose descendants still live in England and Sierra Leone.