‘Tired’, ‘lonely’ and hated by locals: the reality for those sold the digital nomad dream

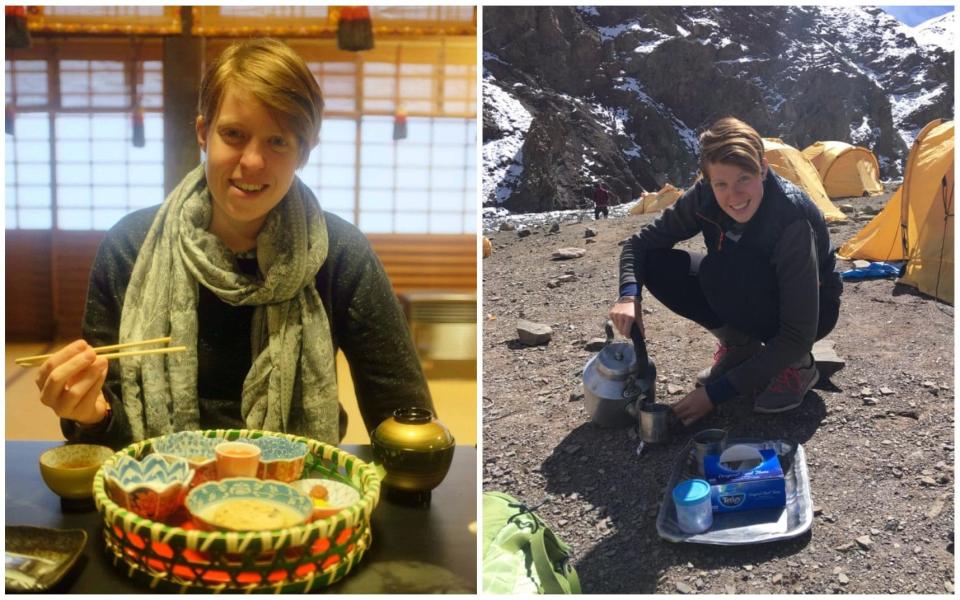

Author and entrepreneur Bex Band first became a digital nomad in 2016. She and her husband Gil left the London rat race to explore Israel then Tanzania, and then simply kept going. He began earning money through freelance marketing work, she launched a blog called The Ordinary Adventurer and a women’s adventure community, Love Her Wild. The newfound flexibility and freedom were “a dream come true – a holiday that never ended”, she says. “If I wanted more beaches, I’d head to an island. More adventure, I could organise a big trek... You meet such interesting people on the road and clock up incredible experiences, from swimming with humpback whales to watching the Northern Lights.”

But two and a half years, and 12 countries in, the sheen began to rub off: “I started to tire of the constant travel,” she explains. “I found it hard to maintain a healthy diet and exercise when I was on the move all the time, and this really started to bother me. I craved to sleep in my own bed, in a familiar room.”

The fun of working from beautiful locations was often frustrated by poor Wi-Fi connections: “I stopped being excited about visiting new places as it began to get ‘normal’. Mostly though, it was lonely. There was never a shortage of other travellers and nomads to speak to, but people would come and go all the time.”

Her long-term friendships began to suffer too: “I drifted apart from lots of people in my life. It wasn’t just the distance; it also became difficult to stay connected to some because our lifestyle was so different.”

In 2020, 10.9 million people described themselves as digital nomads. By the end of 2022, estimates placed their number at around 35 million. During the pandemic, many discovered they could work from home. So why not the beach, then a Mayan temple, then the desert? Places where the rent and cocktails are cheap, and the sun always shines.

Lisbon, Bali and Tulum are among the most popular destinations, while IT and creative service workers are the most common jobs taken on the road. Americans make up more than half of this drifting population and, according to Nomad List, a web platform for globetrotting workers, the second biggest cohort come from the UK.

But while these numbers tell one story, the number of veterans telling a more nuanced, honest one, is rising too. “We first became digital nomads in January 2016,” say Americans Mindi and Daryl Hirsch, who write the website 2foodtrippers. “We planned to travel for a year to satisfy our insatiable sense of wanderlust.” A year became three, in which the pair saw 33 countries and more than 100 cities.

The lifestyle had considerable perks. The couple list “visiting new destinations, eating lots of great food and connecting with new people”. But they add: “While the constant state of motion was exciting in the beginning, it eventually became tiresome – literally.”

After a couple of years “we were almost always tired. Our clothes and luggage started to look ratty. Airbnb had changed to the point that finding good value accommodations was a challenge. Plus, although we built our business while we were digital nomads, it became challenging to fully focus on our work without a proper desk and consistent internet.”

The pair eventually put down roots in Lisbon in 2019. “We feel happy to be settled,” they say. “Not only do we have the sense of community that we craved while on the road, but we also feel healthier, having a well-stocked kitchen and easy access to healthcare. We continue to love hosting dinner parties, sleeping in a comfortable bed every night and having our own products in the bathroom. Plus, our business has grown exponentially since we settled down.”

While some digital nomads are discovering the down-sides of the lifestyle, destinations are also discovering the drawbacks attached to hosting them. According to a March survey, 36 per cent of digital nomads have an annual income of between $100,000 and $250,000. Another eight per cent earn between $250,000 and one million. Attracted by these bank balances, dozens of countries have now introduced so-called “digital nomad visas” (permitting extended stays to work remotely).

The Hirchs’ adopted country of Portugal is among them. Digital nomads must earn at least €2,800 per month to qualify for its new visa, around four times Portugal’s minimum wage. According to Nomad List nearly 16,000 people were remote working in Lisbon last December, where they now find themselves blamed for rocketing rents and house prices. Entire neighbourhoods, detractors claim, have turned into Airbnb enclaves.

As the number of digital nomads rises, other hurdles have been highlighted, from permissions (remote working could put you and your employer under the jurisdiction of that country’s employment laws and taxes, it turns out) to emissions (all those flights...).

Accusations of cultural crassness also rose sharply during the pandemic, when some nomads suddenly found themselves viewed not as glamorous adventurers but as super-spreaders. In 2021, Bali deported American digital nomad Kristen Grey after she tweeted that it was “queer friendly”, offering “elevated lifestyle at a much lower cost of living”, and encouraged others to emulate her move, despite the country’s rising number of Covid-19 cases, a ban on foreign visitors and LGBT discrimination.

Reflecting on his experiences as a digital nomad in a 2021 blog post, the American writer, traveller and vlogger Tom Kuegler concluded: “A lot of the messages put out about the digital nomad lifestyle tend to centre around shucking responsibility... This is an empty existence, and I believe a lot of digital nomads realise this relatively early on in their journey.” Instead, he urges readers to “open their mind, value the locals, and try to make a difference in the communities they’re staying at.”

Some, like the Hirsches and Band, of course do. “I met digital nomads who would check in and out of countries as they would shops in a shopping mall, but that isn’t how I travelled,” says Bex Band. By avoiding flying, taking public transport, hand washing clothes and buying nothing new, she estimates that her carbon footprint was no higher than it had been in her life before, when she would take regular holidays, weekend breaks and shopping trips. Possibly even lower.

She ate in independent restaurants and booked homestays to support the local economy and made every effort to respect and connect with the communities she visited. But she adds: “Now I’ve lived both lives I can tell you the grass is always greener.”

She would still recommend trying the digital nomad life, though. “Even if just to teach you the most important things in life – to realise you don’t need as much stuff as you think you need, to learn to value experiences over things and to experience the great freedom of doing with your days as you wish,” she says. “However, I don’t think being a digital nomad is a realistic life choice for most people long-term... I’m grateful to have had those experiences, savoured those memories and now to have taken the biggest lessons back with me to my new simple life.”