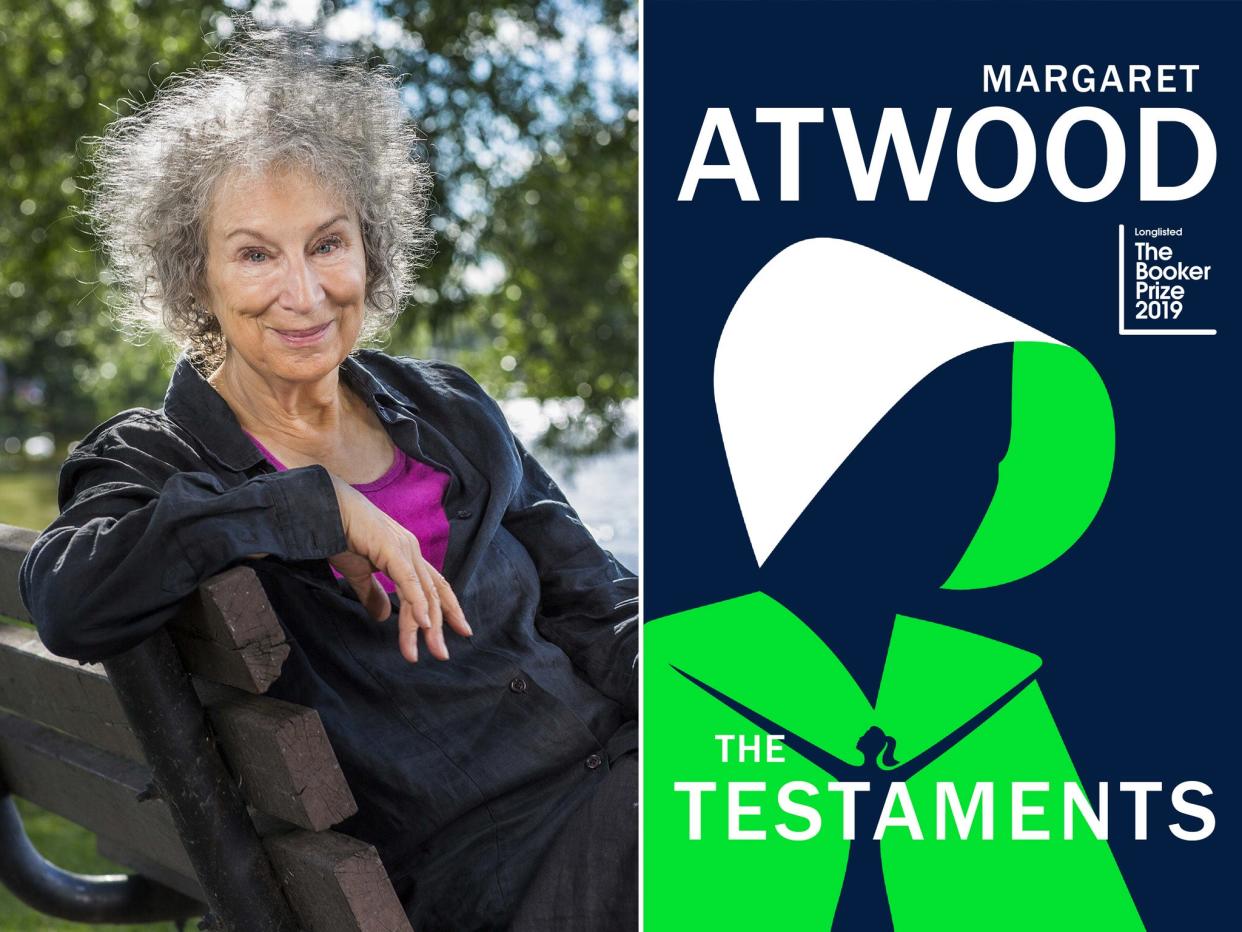

The Testaments review: Margaret Atwood's overly neat Handmaid's Tale sequel is surprisingly fun

You don’t need me to tell you that this is the “literary event of the year”. Thirty-four years after her seminal novel The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood has published a sequel. It’s already shortlisted for the Booker prize. Bookshops are staying open to midnight on release day. Waterstones has a countdown clock to publication on its website – somewhat undermined by Amazon accidentally sending out a first batch early. In doing so, it broke one of the strictest book embargoes ever – The Testaments has been under Gilead-style surveillance, and possibly with good reason: the publishers have apparently been subject to cyberattacks.

So The Testaments has a lot to live up to. As well as all that hype, there’s the genuine brilliance of its predecessor, which has become a touchstone in the age of Trump, and a hugely popular TV series. It cannot fully live up to all of that, but it can and does satisfy our hunger for more. It is an addictively readable, fast-paced adventure towards the collapse of Gilead, a totalitarian Christian state formed in a dystopian America, when falling fertility rates are countered via the sexual enslavement of women (the handmaids). No regime lasts forever – a point already hopefully made in the postscript of The Handmaid’s Tale – and The Testaments looks at how the first blows may be struck from within.

The Handmaid’s Tale, as its title suggests, offered only the tightly focused perspective of one woman, Offred. Its claustrophobia was heightened by her lack of knowledge, of who to trust or how the new world really worked. The Testaments flips this: it’s a broader, multi-perspective book, which takes us both further inside the regime and provides an outsider’s view.

The book’s blurb suggests the reader arms themselves with the thought “Knowledge is power”, and it is presented as three eye-witness accounts documenting what Gilead was really like, as discovered by later historians. They’re by Aunt Lydia, the fearsome woman in charge of the Handmaids, but also two young women – Agnes, brought up entirely within the regime, and Daisy, who was smuggled out to Canada as a baby, but who gets involved in the resistance.

Atwood has said the book came from the wanting to answer readers’ many questions about Gilead – especially how it fell. So it fills in and fills out the original story: not answering what immediately happened to Offred, but skipping 15 years ahead to the next generation, as well as looking back to the early foundation of the state.

It may be a pragmatic choice: the TV show has already continued Offred’s story. But it’s also artistically the more interesting one. It’s fascinating to meet a devout Gilead citizen who’s never known freedom, who sees razor wire and thinks it make her “perfectly safe”. Her religious belief is deeply felt, although I wished Atwood had gone further into Agnes’s eventual crisis of faith, which gets somewhat swept away in the book’s thrillingly action-packed final sections.

Best is getting inside Aunt Lydia’s head. We discover she was a judge before the coup. She chose to save herself, at any cost: “Better to hurl rocks than to have them hurled at you. Or better for your chances of staying alive.” Atwood calmly poses the question: what would you do in this situation?

Her accounts provide the most harrowing sections – but also the most enjoyable to read, delivered with a bone-dry, knowing cynicism (“Gilead had a long-standing problem, my reader: for God’s kingdom on earth, it’s had an embarrassingly high emigration rate.”). Atwood portrays Aunt Lydia as canny and cunning – and complex. She plays the system, yet also appears to be working to overthrow it. But her motivation seems to be a personal vendetta against the indignities she suffered rather than any wider sense of injustice. For all that The Handmaid’s Tale may have been co-opted as feminist iconography in the #MeToo era, Atwood isn’t in the habit of writing simplistic tales of feminine solidarity. This sister, at least, is really only doing it for herself.

Would The Testaments work as a standalone novel? Yes, although it wouldn’t be feted in the manner of the original. Details of the horrors of Gilead unfolded slowly in The Handmaid’s Tale, with its ambiguous ending; The Testaments can feel clunkily expositional and overly neat by contrast, explaining rather than suggesting.

But then, it never will have to standalone – it builds on an existing world, and it has a built-in fan base, which it will surely please. It solves some of the mysteries of Gilead rather than stoking them; whether that’s a good thing or not depends what you want from fiction. But as a reading experience, it’s also surprisingly fun, with its plucky young heroines and juicy (if predictable) plot twists. I was gripped and gobbled it up – and not just because of the time pressures of that broken embargo.

Read more

Margaret Atwood interview: 'White supremacy is always bubbling away'

The book also asks us to be armed with the thought that “history does not repeat itself, but it rhymes”. We hardly need reminding. In an era where #MeToo has revealed the extent of abuse against women’s bodies, where women’s accounts are systematically disbelieved and undermined, where women’s rights to control their bodies are freshly eroded, and where talk of walls and borders and the demonised Other is all on the rise – well, the rhyme of reality with fiction is loud and devastatingly clear.

But for all the cries of “Gilead” that go up whenever Trump, or Boris, or other leaders in Western capitalist democracies grab power (or pussy), what comes most painfully to mind are the places where Gilead was a kind of reality in 1985 – and still is. Women are still treated as the property of men in Saudi Arabia; North Korea’s borders have still not opened.

“How tedious is a tyranny in the throes of enactment. It’s always the same plot.” writes Aunt Lydia. In The Testaments, Atwood changes the emphasis of the plot, to strike a note of optimism – a hopeful reminder that resistance is possible and such regimes do eventually always fall.

The Testaments, £20, was published by Chatto & Windus

Read more

Read more Margaret Atwood interview: 'White supremacy is always bubbling away'