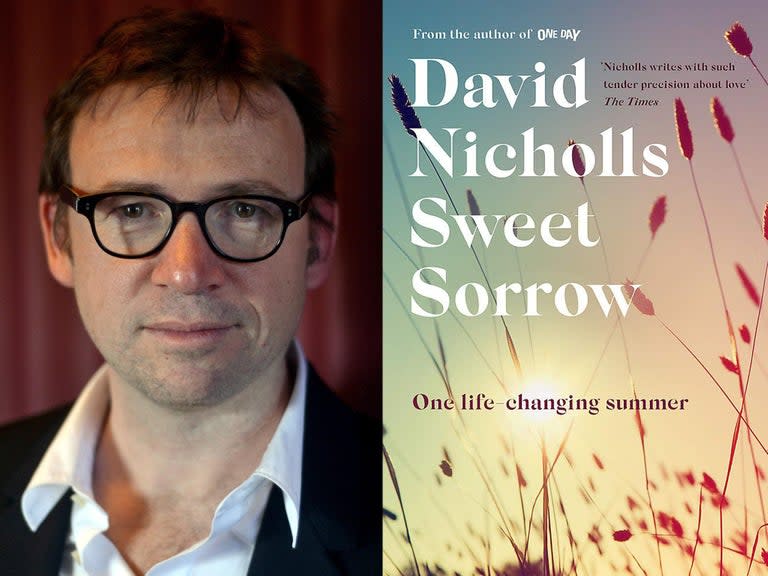

Sweet Sorrow by David Nicholls, book review: Nicholls is just gorgeous on the good bits of being a teenager in this utterly heartfelt book

Does any writer do nostalgia quite like David Nicholls? His bestseller One Day was partly so adored for the way he captured the feeling of being young, being in love, and being confused. He returns to similarly fertile territory on Sweet Sorrow, only stepping back into teenage years, the writing an ideal blend of the gently humorous and utterly heartfelt. It made me feel like something had swollen up inside my chest, and readers are liable to find their thoughts drifting over their own misspent school holidays or crushingly ardent first loves. Bag a copy immediately, because this has got ‘perfect summer read’ smeared all over it like so much factor 30.

Sweet Sorrow is set over a long, post-GCSEs summer in 1997, when our 16-year-old hero Charlie Lewis reluctantly joins a theatre troupe putting on Romeo and Juliet because he fancies the girl playing Juliet – one Fran Fisher. Although told by the adult Charlie, the writing is superbly alive to the way teenagers try to be arch and cool, while also feeling everything so deeply. That said, I would have liked a touch more of present-day Charlie – his current life intrudes only briefly, and remains thinly sketched.

Nicholls is just gorgeous on the good bits of being a teenager: the scene where Fran and Charlie get taken to an absurdly cool grown-up party, and take ecstasy and eventually kiss, is a thrummingly intense evocation of both a first high and first love. I was almost as invested in Charlie finally smooching Fran as I was in my own first kiss.

But crucially, Nicholls doesn’t just do the good bits. Being 16 was crap, for most people, most of the time. Nicholls writes all the rubbish stuff too – and this doesn’t diminish the nostalgia, but rather makes the book feel more truthful and mature.

Charlie isn’t in a good place. He lives in a crap town in the south east, with a crap job at a petrol station, and is expecting deeply crap GCSE results. His parents have broken up, and his father is a depressed alcoholic – although neither of them can use those words, or indeed find any other words to talk about what’s happening. He’s also drifting apart from his mates, lads from school who also can’t talk to each other, the friendship bound by banter and cruelty.

Where Nicholls does have fun is in paralleling the plot of Romeo and Juliet, although – thankfully – this is done with a lightness of touch. That central party could be the Capulets ball, Charlie himself points out. Fran went to the posh arty school while Charlie went to a grotty comp: love across the divide. And Nicholls always writes well on how class manifests in confidence and cultural capital, and Charlie’s insecurity next to Fran’s worldliness brings in a taste of bitterness. His nickname at school is “Nobody”, and he describes himself as the person in the school photo who no-one will remember. I wouldn’t want to give away the ending, but let’s just say Nicholls doesn’t follow a pat narrative where Art and Culture are uncomplicatedly emancipatory. Shakespeare changes Charlie’s life, yes, but it doesn’t magically transform it.

Another thing to cherish about Sweet Sorrow is its recognition of how teenagers construct artful but fragile sense of selves through cultural references. Fran listens to the Romeo + Juliet soundtrack for the Radiohead song, has a favourite Kieslowski film, and likes Thomas Hardy more as a poet than a novelist: “in short, she was as pretentious as to be expected at sixteen”. And the novel will be particularly enjoyable if you happened to be young in the mid-nineties, and can wallow in the references to the Spice Girls (a “musical water-cannon for the boys” at a school disco) or Aztec by Lynx deodorant applied to armpits in “a coat as thick as the icing on a wedding cake”.

The book will also chime with anyone who’s ever dabbled in theatre – Nicholls himself worked as an actor as a young man. He satirises the cringey elements (descriptions of trust exercises made me clench up involuntarily) while embracing the melodramatic joys (the pre-show rituals! the last-night party!). The adults trying to make Shakespeare cool are pitch-perfect too, insisting he was “the first rapper”. But the possibility of discovering, well, truth and beauty in these old plays is allowed too. Juliet’s speech, urging the night to take Romeo and “cut him out in little stars”, repeats and resonates – because how could it not in a story of such shining but tender first love?

‘Sweet Sorrow’ is published by Hodder, £20