Students going home for Christmas tell of ‘piling into Covid carriages’

The six-day student Christmas travel window might have opened yesterday, but Finley Gore, 18, isn’t going anywhere.

The first-year Manchester student does plan to spend the festive period with his family in east London, but he is deliberately delaying his campus exit until after the rush. Several of his relatives are at high-risk if they catch Covid, so he is nervous about the germs he’ll pick up on trains rammed with students from across the country.

“It’s like they are piling us like livestock into little Covid carriages,” the English literature student tells me, speaking from the flat he shares with nine others. “I couldn’t live with myself if I gave Covid to my family.”

Finley Gore, a first year English literature student at the University of Manchester

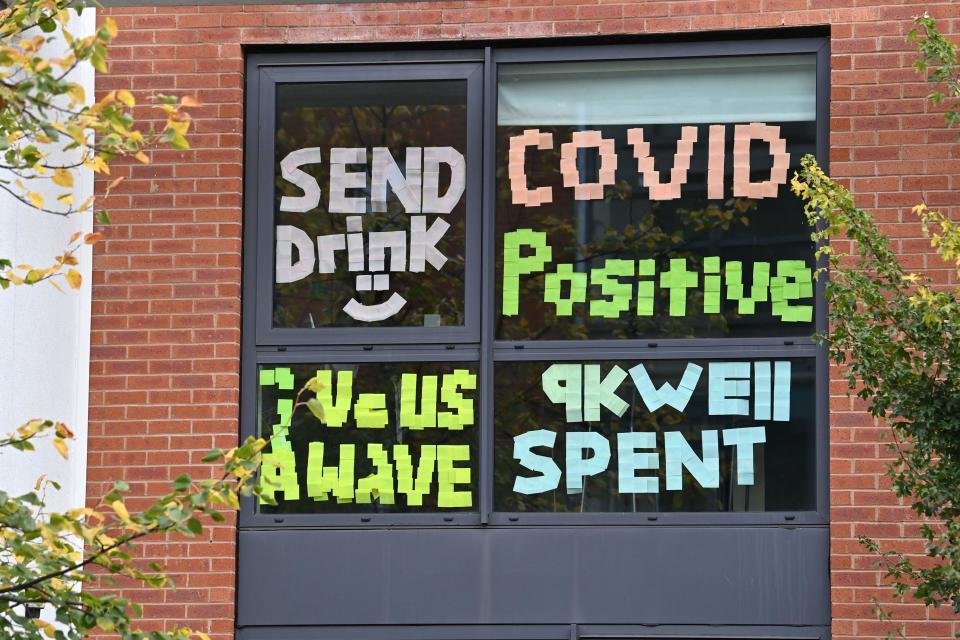

Like tens of thousands of students across the country, Gore has had a rollercoaster of a term. While pictures of lonely 18-year-olds trapped in their rooms dominated the front pages in September, for him and his fellow freshers on the university’s 4,000-strong Fallowfield campus, that “prison-like” atmosphere has been their reality long since the cameras left.

At one point in September, Manchester had more daily deaths than the whole of Italy. At least 55 per cent of all cases were among those aged 17 to 21.

Gore laughs when I ask him to describe the term, listing some of the low-lights of the last 10 weeks: waking up to find their accommodation surrounded by fences; the strikes over fees, including the occupation of a university building; the “appalling” conditions in halls, from being supplied with out-of-date food to silver-fish infestations.

And spending so much time crammed into the same four walls has led to “flat dramas”. “It’s basically Big Brother,” he says. “Except no-one gets evicted.”

Gore is upbeat about his freshers’ term given the circumstances — he realises he’s been lucky with the people in his flat and at least he’s had the chance to get involved in student activism. But many of his peer-group aren’t so chipper.

Online learning has been “challenging” at best, with students reporting longer hours to get their heads around virtual content, little contact from their tutors and widespread cheating in exams. “There’s nothing to stop you Googling the answers — obviously you’re going to if everyone else is,” admits one Glasgow fresher.

Glasgow student, Harry Butcher, 19, says there’s little point being on campus when even the library is essentially out-of-bounds. “I’m not going to queue for an hour,” he says of the wait for a seat. “It’s a library not an Apple Store.”

Socially, too, it’s been a hard term. Butcher says it’s been difficult to make friends outside his flat — if he leaves halls after dark, security guards stop him and ask where he’s going - and that’s if you’re lucky enough to get on with them.

Kasey Ward, a first-year film student at Kings, says the people in her flat are “awful” but the university won’t let her move. “I thought it would be a lovely experience, but it’s been the opposite,” she reflects on her first term away from home.

Meanwhile living conditions for many have been “diabolical”. Lauren Corelli, student union president at Goldsmiths in London, described some halls as “public health disasters”, adding: “We’ve had some quite shocking calls from people who are very much at the lowest ebb.”

Issues like these have caused student mental health problems to spiral. One Manchester fresher, Finn Kitson, 19, was found dead last month after experiencing severe anxiety while in isolation. Students across the country report that mental health services are insufficient and oversubscribed.

Students at King’s College London face month-long waiting times for mental health appointments, while online counselling service Student Space has reported a 20-fold jump in calls over the past three months.

There is also growing anger over fees. Despite ministers agreeing to discuss the reimbursement of some tuition costs last month, a recent survey found that just one in every 30 students who have requested refunds has actually received any money back.

“We keep being deferred to different departments,” says Liv Facey, a first-year student rep at King’s who says her peers feel they’re working harder than ever with lectures that feel like YouTube videos and no bar jobs available to help fund their studies. Of course, she and her peer-group aren’t expecting to be repaid the full £9,000 that this year has cost, “but £1,000 would be something”.

Some students have decided to take this battle over fees into their own hands. More than 1,300 students at the University of Bristol have been staging the biggest rent strike in recent history. In Manchester, the occupation of the university building by a group of first years resulted in a 30 per cent rent reduction last month, and Gore is among a growing movement called #9K4WHAT?, encouraging freshers from Newcastle to Bristol to revolt by cancelling their direct debits.

“We were lied to and brought onto unsafe campuses, forced to pay insane rent for facilities we can’t even access,” Manchester student and member of the group Izzy Smitheman tweeted last month ahead of a protest.

Smitheman’s tweet raises the most pressing question: why were students allowed to come to campuses in the first place? “Students feel shoved around and blamed [for spreading Covid],” says Marta Mora, a third year politics and philosophy students in Newcastle.

Many feel “tricked” into moving to universities that were unprepared for spikes in infections, and now they’re being forced to make unsafe journeys to be with their families for Christmas.

Universities have been handed facilities to offer two rapid Covid tests, three days apart, for each student going home, but the practicalities are much more complex: what if students have exams during that six-day period? How can they be expected to keep apart on busy trains? And what will this do to train fares?

Second-year languages student Lucy Nichols, 21, said tickets were already “astronomical” in November: she’ll have to fork out at least £100 to get home from Manchester to London.

Some students cannot go home at all. Many with families abroad or who are shielding face the prospect of Christmas alone on campus. Bristol fresher Laura admits she is looking forward to a one-off “friendsmas” - several flatmates in the same position are grouping together - but others aren’t so lucky.

Thomas, a first-year psychology student in Lincoln, wants to protect his brother who is shielding so will spend Christmas in his university house with a friend and a takeaway. “Seeing other people doing what they want and essentially having a week of freedom feels unfair,” he says.

Is there hope for a happier student experience in 2021? Unfortunately, Covid on campus won’t be a one-term wonder. Yesterday, ministers announced plans that involve asking students to stagger their journeys back to university over five weeks. Those on practical courses requiring face-to-face teaching will be encouraged to begin the wave, with the aim of having everyone back by February 7.

But what about arts students? Nichols, who studies Spanish and Arabic, says she’s already concerned about her studies in January — she has six siblings at home and no desk — but if she does delay coming back, doesn’t she at least deserve a rent reimbursement for the weeks she’s being forced to miss?

Not all students are comfortable coming back in January, even if they can. Harry Martin, a second-year chemistry student at Leeds, says he doesn’t plan to return to campus until later in the term for fears of a spike in infections — he knows everyone will be mixing with friends in the break, not just their families. A couple of freshers he knows are considering dropping out and not coming back at all.

But it’s not all doom and gloom, says Martin. He’s secretly enjoyed being able to roll out of bed just in time for online lectures, and the pandemic has certainly forced students to mature more quickly. “We’ve had to have more adult conversations,” says Nichols, recalling how her house all went down with Covid earlier in the term. “We had to work out how we were going to eat, how we were going to keep each other safe.”

If university is about giving young people life experience, this year’s intake have certainly had that in abundance.