Stoking Frida-mania: A new exhibition reveals how Frida Kahlo crafted her identity

Self-invention has always been part of any painter’s repertoire. Think of the way Rembrandt made and remade himself throughout his life. But is obsessive self-scrutiny necessarily a good thing? Not necessarily.

These days the presentation of the self can be an obsessive preoccupation with less happy outcomes. Young artists often feel a pressing urge to frame themselves by gender and identity alone. It is often the sole justification for the art that they make. If those boxes are ticked, all will be well.

Not true. The consequence of that approach is that the object, that which exists outside the self – the rest of the world, for example – is all too quickly forgotten. The presentation of the self has been prioritised to the near obliteration of all else.

Bad art cannot be forgiven on the grounds of fashionable self-presentation. But perhaps it can be forgiven when the self-preoccupied happens to be blessed with the talents of a Rembrandt – or a Frida Kahlo.

The impact of the idea of Frida Kahlo, the disabled Mexican painter who died in 1954 (her leg was amputated the year before), has been a profound one. In fact, you could almost call the world’s obsession with her a species of Frida-mania.

Jean Paul Gaultier appropriated her surgical corset for his spring/summer collection of 1993; Italian Vogue devoted an entire issue to her in December 2014. Beyoncé made a Halloween costume in her honour. And now the Victoria and Albert Museum is putting on display an entire exhibition devoted to the creation of her own self-image called Making Her Self Up.

The exhibition was made possible by the unlocking of a door.

In 2004, 50 years after her death, a room in the Blue House south of Mexico City – a residence built as a family home by her father – was opened for the first time. It contained thousands of her most intimate personal possessions, which included her surgical corsets (made of leather, supported by a metal frame), her prosthetic leg, her lipsticks, eyebrow pencils, nail varnish (red), pills, face creams (Chanel no 5 Lotion), jewellery, letters and clothes.

Helena Rubinstein had gifted her with powder compacts. She not only wore clothes that she had collected (often from flea markets) to ravish the human eye, but also made them or remade them, and embellished them to her fancy.

Kahlo’s life was a long struggle against adversity. She contracted polio at the age of six, and was left with one leg shorter than the other. At the age of 18 she was involved in a tram accident, and suffered injuries so profound that she had to undergo multiple operations throughout her relatively short life; she died at the age of 47.

She began to paint when immobilised in her bed. And the painted version of herself – about a third of her works are self-portraits – was, you could argue, a way of claiming back her own life, of asserting her own identity.

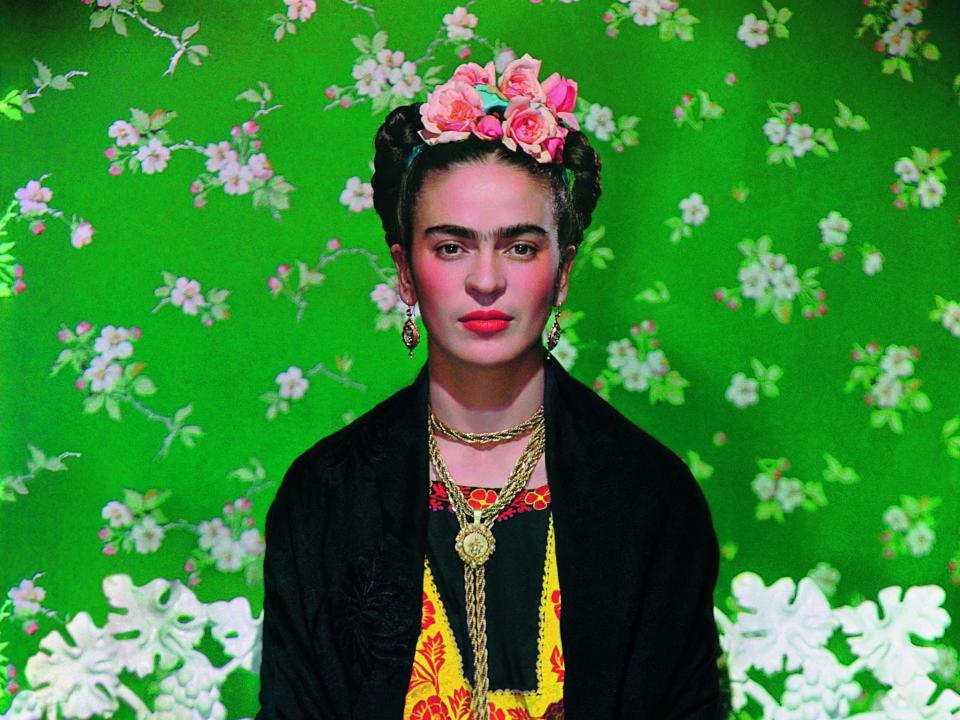

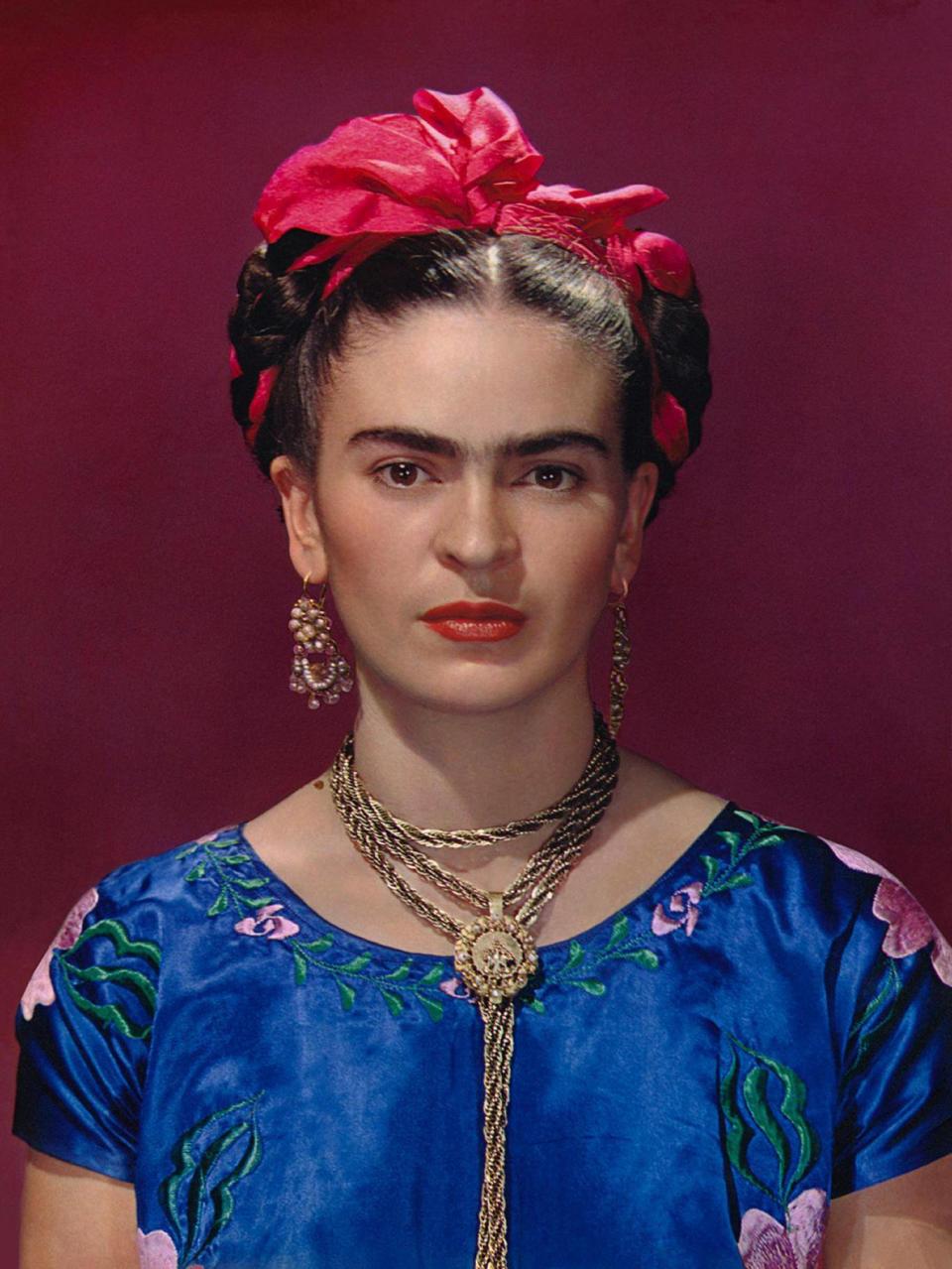

It was an identity which, as this exhibition demonstrates, was entirely self-made. She lived in thrall to her mirrors. She herself became the work of art that she painted so assiduously.

It was an art which both revealed her to the world in all her fabricated splendour, and kept hidden from view her brokenness and her extreme fragility. It was an identity which deftly encompassed ancient and modern: though the imagery of her paintings is steeped in Catholicism, she herself was an atheist.

She lived though turbulent times – at one point, she changed her birth date from 1907 to 1910 in order to identify herself with the beginning of the years of social and political turmoil which became known as the Mexican revolution. This movement, according to the great poet and essayist Octavio Paz, amounted to “a discovery of Mexico by the Mexicans”, a wresting back of the country’s very identity from the colonisers of the past.

Her marriage to a fellow Mexican artist, the muralist Diego Rivera, took her to America, where her appearance was much remarked upon. She often dressed in traditional Zapotec costume from the Tehuana region – a nod in the direction of the power of matriarchy. Her heavy jewellery, one observer commented, “clanked like a knight in armour”. She wore long chains, coral beads, an Aztec necklace. Her teeth gleamed gold. The exhibition includes her prosthetic leg, with its highly decorated red boot.

Her sexual identity fluctuated from masculine to feminine to androgyne. When young, she posed as an adolescent boy; when older, she often opted for a different kind of beautiful self-exposure (or self-concealment): extreme femininity. The eyebrow pencil she favoured – this too is in the exhibition – was called “Ebony”, and her favourite Revlon lipstick was named “Everything’s Rosy”. The cheeks were rouged.

Yet her monobrow, which rose up through the eyebrows like the flap of a black bird’s wings, was often fiercely emphasised in her portraits, and the skin above the lips – they were generally tight-lip-closed – was delicately moustachioed. She was always proud to be a mestizo: part German-Hungarian, part Spanish-Indian.

It is all these objects – that from which Frida Kahlo forged her own very particular identity – which preoccupy us at the V&A. The paintings are mere adjuncts to the story of what this woman made of herself.

‘Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up’ is at the V&A, 16 June-4 November (vam.ac.uk)