Searching for Sam: Adrian Dunbar on Samuel Beckett, review: a life-affirming portrait of the wordsmith wonder

Stephen Rea was telling fellow Irish actor Adrian Dunbar about the time that he worked with Samuel Beckett at London’s Royal Court Theatre in 1976. After the playwright had watched a rehearsal of Endgame, director Robert Kidd asked him: “Well, Sam. Happy?” In reply, Beckett simply “roared his leg off”.

Rea and Dunbar dissolved into wheezing laughter at the very idea of asking “the arch pessimist of the 20th century” if he was happy. It was just one of many lovely moments in Searching for Sam: Adrian Dunbar on Samuel Beckett (BBC Four).

Acclaimed screen actor and theatre director Dunbar is best known as cult hero Supt Ted Hastings from hit police drama Line of Duty. He’s usually only interested in catching bent coppers, but here Dunbar shared his own true passion. He has long felt a connection to Beckett, whose formative years were spent in Dunbar’s native Fermanagh. Dunbar even co-curates an annual Beckett festival in his hometown of Enniskillen.

This impressionistic film followed Dunbar, a thoughtfully avuncular presence, as he travelled in Beckett’s footsteps to the places that shaped him. He traced his solidly middle-class Dublin roots, then walked the Wicklow hills where Beckett and his father were “fanatical trampers”.

We heard about the “savage loving” of his mother and his move to Paris in the 1920s, where he became secretary to his hero James Joyce. During the Second World War, Beckett put himself in the firing line by joining the Resistance. “I prefer France at war to Ireland at peace,” he famously said.

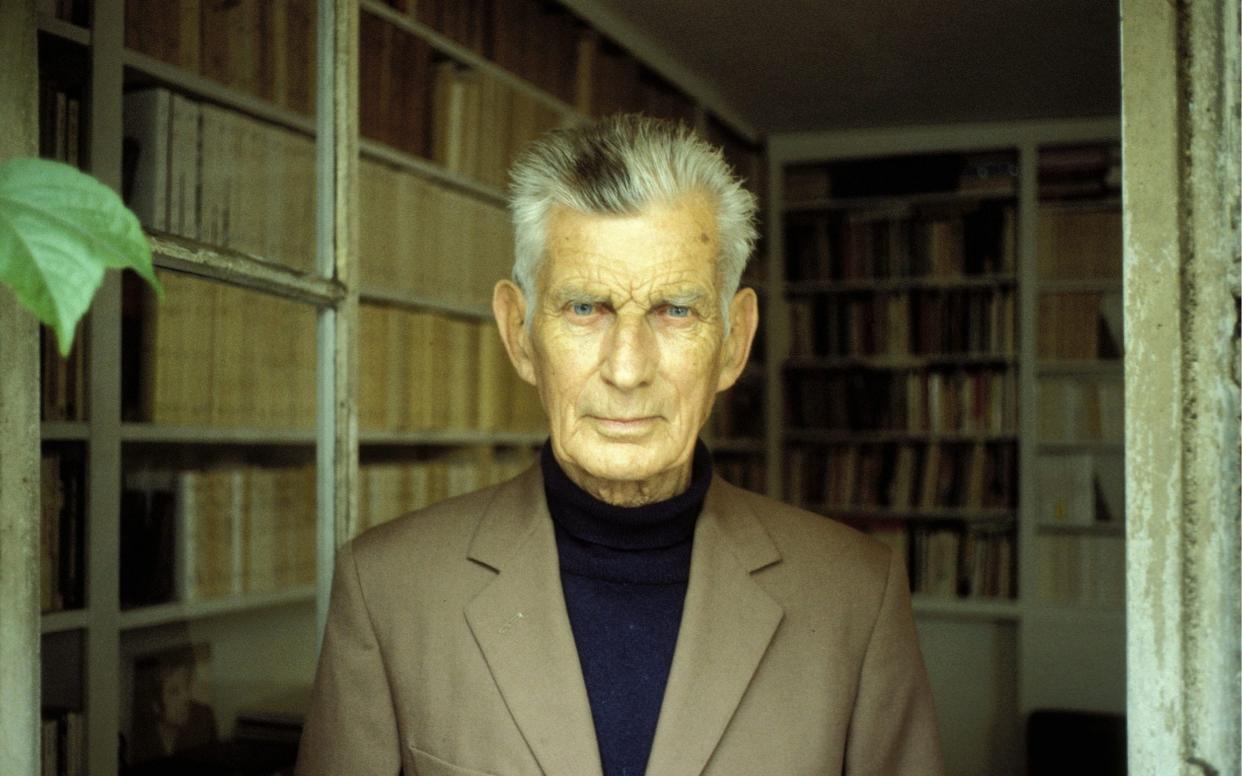

Dunbar met the dwindling number of collaborators who’d met this intensely private man. As well as Rea, there were thesps Barry McGovern and Clara Simpson, photographer John Minihan, and biographer James Knowlson, who described the writer as resembling “an Aztec eagle, upright like a middle-distance runner”.

Experimental and existential, Beckett isn’t the easiest author to love, but this was a welcome reminder of the pain and compassion at the core of his work. Far more than a South Bank Show-esque biography, it was an elegiac portrait of the artist as a young man, packed with haunting quotations and windswept landscapes.

“I’ve often heard people say Beckett is difficult and bleak, but that’s not true for me,” said Dunbar. “I’ve found engaging with his work to be both life-affirming and uplifting.” This fine film achieved something similar.