Sean Connery’s dark night of the soul: how The Offence took Bond into the abyss

At the beginning of 1971, Sean Connery was not only the biggest star in the world, but he had signed a then-record breaking deal that made him the best paid actor alive, too. The previous James Bond film, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service – the first without Connery as 007 – had underperformed at the box office, making $82 million worldwide as opposed to the $112 million that Connery’s swansong, You Only Live Twice, had grossed.

It was now felt to be of paramount importance to bring the star back for one final appearance as the super-spy in Diamonds Are Forever. In order to lure the reluctant Connery, David Picker, the then-president of United Artists, offered him a peerless deal. Not only would he be paid $1.25 million to reprise his Bond role, but he would also be able to make two films of his choice, funded by the studio. It was a generous, even foolhardy, offer, but Connery was box office gold: surely whatever he appeared in would be scattered with the Bond stardust, and would prove highly profitable, too.

Unfortunately, Picker and United Artists had underestimated the actor. Even while he had been playing 007, Connery had been drawn to darker and more challenging projects; he had played a near-sociopathic rapist in Hitchcock’s 1964 thriller Marnie and a brutish military prisoner in the 1965 drama The Hill. The latter was directed by the American filmmaker Sidney Lumet, then best known for his courtroom thriller 12 Angry Men, and he and Connery got on well together.

They would reunite shortly afterwards for the surveillance thriller The Anderson Tapes, which was released around six months before Diamonds Are Forever. Thereafter, Connery hand-picked Lumet to direct what would be, by far, his darkest and most disturbing film, a walk on the cinematic wild side that took its leading man to places that he might have preferred not to venture into.

Connery had first met the playwright and screenwriter John Hopkins during the production of Thunderball in 1965. The film’s script had been a nightmare from a rights perspective, but Hopkins, then best known for being the screenwriter and script editor of the popular British police series Z-Cars, had been brought in at a late stage to polish the dialogue; he had received a coveted co-screenwriting credit, along with the American Richard Maibaum, for his work on the film.

He had impressed Connery with his diligence and professionalism, and so, when his first play, This Story of Yours, was staged at the Royal Court in 1968 – then as now home of the most provocative new writing in London – Connery was in the audience. Hopkins’s drama, a series of dialogues revolving around the psychological collapse of a deeply disturbed detective, was challenging and abrasive, and a box office failure. When it closed after a mere three weeks, the Financial Times’ theatre critic commented sadly that “the English do not deserve to have great men”.

It was a stroke of irony, then, that the revival in the play’s fortunes lay with a Scot and a New Yorker. With Connery now emboldened by the deal that he had secured from United Artists, he formed a production company, Tantallon Films, which was dedicated to finding and producing new projects for Connery to appear in.

Even as the actor freely confessed that he was a thespian, not a businessman, he cited the example of Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, who had used their international fame to make films that they believed in, not least their experimental 1967 adaptation of Doctor Faustus. Connery believed that This Story of Yours was the perfect first project for Tantallon to work on, saying to Lumet that, although it was a controversial, envelope-pushing subject, with the potential for outrage, he had not gone into acting to play safe. When the director read the script, his verdict was simple: “devastating”.

Hopkins made minimal changes to his play in order to open it up for the cinema, but the basic structure remained the same. Johnson, a middle-aged detective sergeant, has been worn down by decades of dealing with criminals. When he interviews Baxter, a suspected child molester, he finally breaks down and beats the man to death, after being goaded into violence by Baxter’s suggestion that Johnson, too, would like to commit the kind of crimes that the alleged perpetrator has been arrested for.

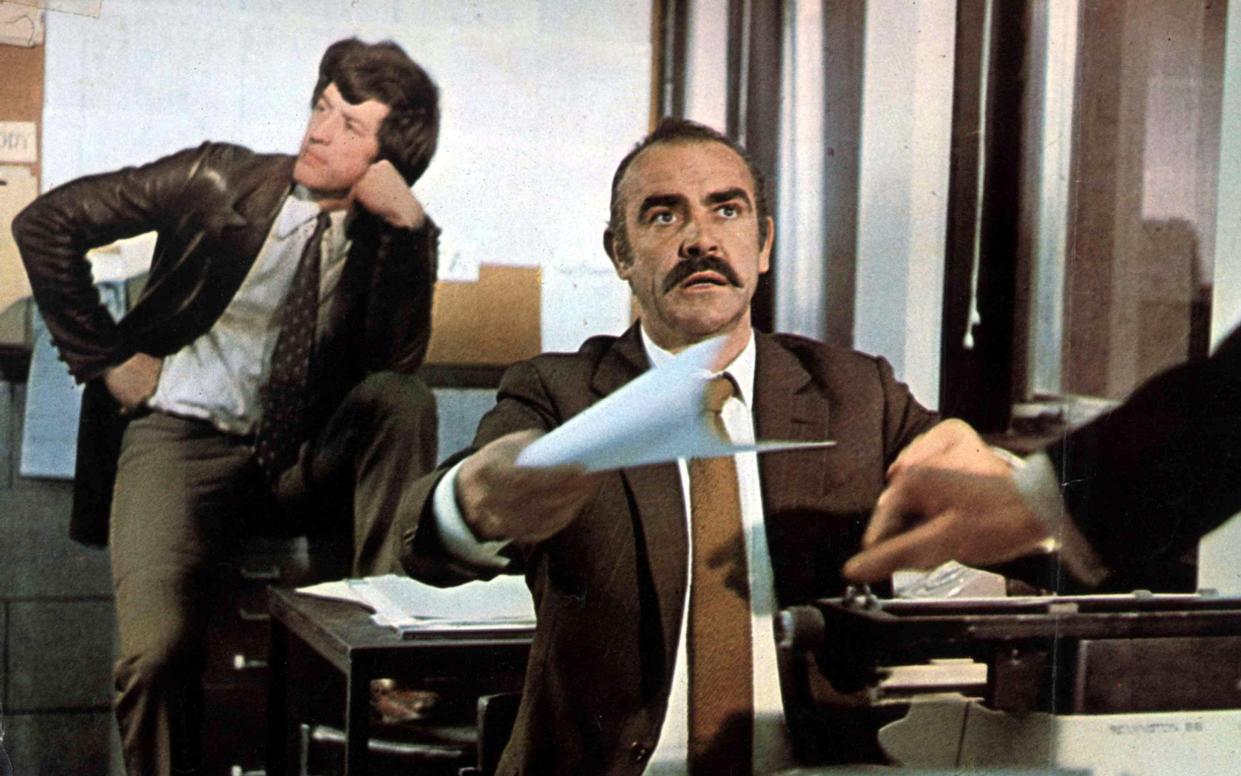

Connery and Lumet assembled a strong cast of British character actors, including the veteran Trevor Howard as Connery’s superior Cartwright, Harold Pinter’s wife Vivien Merchant as Johnson’s semi-estranged spouse Maureen and Ian Bannen, who had starred alongside Connery in The Hill, as Baxter. It was budgeted at a comparatively meagre million dollars, meaning that even if it flopped, United Artists stood to lose little, and would be filmed mainly at Twickenham Studios in a mere twenty-eight days, to allow Connery to move onto other, more lucrative films afterwards.

Its cast had doubts about the project’s viability from the beginning. As Bannen said later, “it was a cracking play, but it presented real problems in terms of commercial cinema. All the actors working with [producer Denis O’Dell] and Sean loved it, but it would be foolish to say we expected it to have anything like a Bond impact.” Connery, however, was closely involved in the film’s production from the outset, including suggesting that the play’s more ambiguous title be changed to the more straightforward The Offence. This was something that Bannen suggested was unwise: “In Italy or somewhere I saw it go out as In The Mirror, Darkly, using the Shakespearean reference, and I felt that was more appropriate. The Offence spelt out grimness.”

Its production was appropriately gruelling for its actors. Merchant, who had a long, intense domestic scene with Connery, later commented: “I used to hear these stories about how much film actors were paid and I would think that was a great deal of money for little work. After I’d finished [the film], I thought it should have been ten times as much.” While Connery had announced that “the premise was to make a picture that people could participate in, in every creative way”, this participation had its downside: in the scene in which Bannen’s character is beaten to death, the actor wore padding under his clothing, so Connery’s savage blows landed for real. Bannen later wryly commented that “in those last scenes I suffered his true-to-life playing.”

Its director, too, altered his usual style of filmmaking. While previous films of Lumet’s had been defined by a simple, almost gritty realism, he now threw himself into a far more experimental register: from the opening scene, which uses slow-motion, unusual camera flare effects and Harrison Birtwistle’s strange, atonal score – the only one that he ever composed for cinema – to denote the aftermath of the eponymous crime, the filmmaker was deliberately striving for a more poetic effect to counterpoint the brutality of the events depicted on screen. (Connery later commented that Lumet went “a bit European on us”.)

Yet at the time, the star welcomed this shift away from the cartoonish Bond pictures. When asked who his favourite director was, he did not respond with Lumet, or Hitchcock, or any of the other English or American titans of the day. Instead, he replied “Ingmar Bergman”; Connery hoped that The Offence would have the impact of Bergman’s most recent film, the Oscar-winning Cries and Whispers.

Nonetheless, when it was completed, he was unconvinced about its commercial potential. Although the director John Huston – who would later direct the actor in The Man Who Would Be King – responded to the film rapturously, telling Connery that the final forty minutes, in which Johnson undergoes a psychological meltdown, were some of the finest he had ever seen in cinema, other, less partisan viewers were less impressed. In order to gauge the reaction of ‘ordinary’ people, Connery invited porters and cleaners from his offices to a private screening of the film before its release. As he later said, “I tried to find out how people would react. The film’s story, I know, is probably difficult to take.” The response was not entirely what he had hoped for. “The cleaners and the porters all said they liked the acting, but were not too forthcoming about the subject.”

When the film was finally released in January 1973, it opened at the Odeon Leicester Square, London’s largest cinema. When Diamonds are Forever had been shown there, at the end of 1971, it had been a huge commercial success, with queues stretching round the block well into 1972. The Offence, however, attracted no such interest – as the actor acknowledged, “[the cinema] was just too big” – and, despite Connery’s pre-eminence as a commercial star and respectful, if slightly horrified reviews, the picture was not even released in such major territories as France. Although the film eventually made its money back, it took nearly a decade before its modest budget was recouped, and the second film that Connery had agreed to make with United Artists was quietly dropped, despite plans for pictures as eclectic as a Germaine Greer-scripted film about the decimation of the Aborigines.

Its star remained sanguine about the film, even if he later quipped to the interviewer Mark Cousins that the only people who saw it were his family. Connery reserved his blame for UA’s lack of distribution, saying: “There was no faith in Sidney nor me. Nothing. They did nothing for it and released it through the toilet.” Yet he was also intelligent enough to realise that it was the wrong film for the wrong time, just as the original play had failed to connect with audiences. People wanted escapism and fun, not dark, brooding psychological horror. He acknowledged this by saying: “Some people may detest [Johnson, but] the British have always been so anti-analysis in every sense of the word… this film goes into analysis of why this detective became what he is.”

Five decades after its initial release, The Offence feels like a film far ahead of its time. Today, we are almost at saturation point with grim, downbeat police procedurals that explore the fractured psyche of their anti-heroic protagonists, but back then, to audiences more comfortable with the more straightforward morality of Hopkins’s Z-Cars, the idea that a policeman might be every bit as morally rotten as the men who he interrogates was a challenging and unsettling one.

Although Connery worked with Lumet twice again and continued to take on critically acclaimed roles as lawmen, he never took himself so far out of his comfort zone ever again. Perhaps, like Johnson, he had stared into the abyss while making the most disturbing film he ever worked on, and did not like what he saw there. It was undoubtedly to his personal benefit, but it remains a loss to cinema.