Sam Mendes: ‘Who would make a great Bond villain? José Mourinho’

The office of Sir Sam Mendes in Covent Garden is generously and chaotically decorated, even cluttered, with mementoes from more than 25 years as Britain’s pre-eminent theatre and film director. On one wall is the envelope first opened and read by Steven Spielberg revealing Mendes had won the Oscar in 2000 for best director for his debut film American Beauty. On the floor is a poster for The Blue Room, the 1998 play he staged at the Donmar Warehouse, with Nicole Kidman in the lead, which made headlines around the world and kick-started a revival in British theatre. There are photos, with gushing dedications, from many of the actors he has worked with. One from Judi Dench, dressed as M on the set of the 2012 James Bond movie Skyfall, reads: “Well, you can try it, but it won’t work” – a line Mendes said to her in 1989, when he was 24 and they were working on a production of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, and has never been allowed to forget.

Mendes, dressed head to toe in black with a jaunty scarf round his throat, walks in and catches me looking at an incongruous photo: the famous one of Vinnie Jones grabbing Paul by the Gascoignes during a match in 1988, signed by both players. It’s just gone 4pm and I ask the 57-year-old Mendes how his day of publicity has been. He gestures at the picture and smiles: “That is subtitled: ‘Releasing a movie.’ That’s how it’s been.” The parallel is clear: the thuggish press squeezing the balls of the delicate creative.

For the most part, Mendes has been treated pretty well by critics over the years, but he is aware that the pressure to flog your new project is greater than ever before. “The truth is that at least half the movies I made would now be going straight to streaming, including probably American Beauty,” says Mendes, of the film that went on to win six Oscars, including best picture. “And it makes me sad that one has to question the nature of the film before you make it and you have to work doubly hard – which is why I’m here – to sell a movie when it doesn’t have an obvious big-screen commercial upside. When you make a smaller-scale movie, something more contemplative, a stiller, more character-based drama, you have to work triply hard to just get people to come out and see this rather than wait for it to appear on their television.”

Mendes is talking about Empire of Light, a tender, subtly powerful film that he has written and directed. Set in the early 1980s, it follows Hilary (the by now almost inevitably brilliant Olivia Colman), who manages a grand old cinema, the Empire, in an English seaside town, while also dealing with bouts of debilitating depression. Mendes’s love of the cinema, and belief in the transformative power of sitting in a dark room with strangers watching a film, is obvious. But he is also keen to show the unlikely bonds such places can foster – in Hilary’s case with a ticket-seller, Stephen (Top Boy’s Micheal Ward) and projectionist Norman (Toby Jones) – even during the furious upheavals and racism of Thatcher’s Britain.

The story of Empire of Light is a profoundly personal one for Mendes: not only was he a culture-obsessed teenager during this period, but he was raised mainly by his mother, who had multiple breakdowns while he was growing up. However, when he started to work on the screenplay during the first lockdown, Mendes was adamant that it should not be directly autobiographical.

“Hilary is based on my mother in one key area, which is her fight with mental illness,” he says. “But she’s not my mother: my mother didn’t grow up on the south coast; Hilary, the character, doesn’t have any children. So I wanted to pull myself out of it. Margo Jefferson, the US writer, has a great phrase: ‘How do you reveal yourself without looking for love or pity?’ I didn’t want to put a little boy in the movie, and make people think: Awww, didn’t he have a tough time? I wanted to take that little boy out of the film, because I wanted it to be about her and her struggles. So I suppose I exist in the film as the camera, but not as a character.”

But then all of Mendes’s films and plays have a strong personal connection, even if sometimes you have to dig deep to uncover it. In 2014, he gave a lecture on 25 rules for “happy directors” and one of them was: “It’s not just enough to admire a script, you have to have a way in that’s yours and yours alone.”

Mendes had a somewhat peripatetic childhood: born in Reading, moved to Manchester, then Primrose Hill and finally Woodstock, outside Oxford. His parents separated in the 1970s, but his father, a Portuguese-Trinidadian English professor, would come back into his life when his mother was struggling with her mental health. Growing up, Mendes was obsessed with cricket – he still is – and was a standout talent at Magdalen College School in Oxford and then Cambridge University, where he studied English and graduated with a double-first.

If there’s a consistent trait in Mendes’s output, it’s that one project typically bears very little relation to the last. The film before Empire of Light was 1917, the kinetic tracking of a British solider in the first world war in what appears to be a single continuous shot. “I don’t want to always make the same film,” Mendes explains. “If the first movie you make is successful, you have to accept you’re going to be learning – and you do still have lots to learn – in public. So I always felt that the Oscar was to be treated like a bank loan, which would be paid off over a number of movies. And around about Skyfall I thought, ‘Yeah, I think I’ve paid off my bank loan now! Now I can do what I feel like doing.’”

Alongside the movies, Mendes remains a powerhouse in theatre. He made his name as artistic director at the Donmar Warehouse in the 1990s, but even as the offers from Hollywood rolled in, he would always return to stage productions. So it was, after two Bond films, Mendes directed The Ferryman by Jez Butterworth (who also wrote Jerusalem), first in London in 2017 and then New York, winning both Olivier and Tony awards for best director. It was Mendes’s first collaboration with Butterworth, but the pair became close friends and share a box at Arsenal.

Mendes’s production of The Lehman Trilogy – a generational saga that started life at the National Theatre in 2018, before transferring to the West End, and then Broadway, where it won five Tonys, and Los Angeles – is now coming back to London for a limited season with a new cast. In May, he directs a new play at the National, The Motive and the Cue, which is written by Jack Thorne (whose previous work includes Harry Potter and the Cursed Child) from Mendes’s original idea, about the celebrated 1964 production of Hamlet on Broadway in which Richard Burton was directed by John Gielgud, while Burton’s new wife Elizabeth Taylor looked on.

All of these projects are close to home, which is in the countryside north of London. This is no accident: Mendes met his wife, the British classical trumpet player Alison Balsom, in 2015, and they have a five-year-old daughter, Phoebe; Mendes also has a son, Joe, with the actor Kate Winslet, to whom he was married from 2003 to 2011. These days he has less desire to travel.

There’s another advantage: Mendes gets to watch the cricket, and this year is an Ashes summer, so he wants to make sure he’s around for that. “Frankly, I think we’ve got a good chance,” he says. “They’re going to crash and burn a few times, but – excuse the pun – they are going to be stoked for the Ashes.”

Before all that, Mendes has to endure the grilling of friends, former colleagues and Observer readers in our You Ask the Questions feature. With all the delicacy of Vinnie Jones, we get started…

• Empire of Light is released in UK and Irish cinemas on 9 January; The Lehman Trilogy is at the Gillian Lynne theatre in London from 24 Jan to 20 May. The Motive and the Cue opens at the National Theatre on 2 May

Olivia Colman

Actor

You were a “young carer” before we really knew what that term meant. How has that experience in your childhood affected what you do now?

An enormous amount. What was normal for me was to be looking out for myself when I was very small, and looking out for my own parent when I was very small. And I suppose the feeling of lack of control of my own life and my own domestic environment led me into a career where I could exert much more control. A career where I was creating alternative universes and populating them entirely with people that I could tell what to do… you do the math! So yes, I think it was a defining feature of my life before I was 18. And a lot of what Empire of Light is about comes from observing someone who was losing control, just as my mother did.

Judi Dench

Actor

Any work going?!!

Always for Judi Dench. Seriously, though, it is impossible to describe, particularly in Judi’s presence, the impact that working with Judi when I was 24 had on me. And how effortlessly she can teach without appearing to teach. Also [she was] the first actor I met who managed to take the work seriously without taking herself too seriously. A bit like Olivia Colman, she just makes other people around her act better. So I know she would not have expected my answer to be a paean of praise, much as I would love to be rude, but working with her was a huge moment in my life.

Who would you recommend to be the next James Bond? Who do you think would make a great Bond villain?

Dave, IT worker, Nottingham

I think Dave could have a future. Frankly, Dave is as likely as the next man. And I want the headline, “Dave to be next James Bond.” I have no idea. They’ve made it so difficult for themselves for two reasons. One is they turned the franchise into something extraordinary with Daniel Craig. If you think about the actors that might have been up for the role after Pierce Brosnan, a lot of people would have said, “No way.” They would not have even been considered for the role, not wanted to be considered for the role. Now, there’s barely an actor in the world who would turn it down. And that’s because of Daniel and because what’s happened to the franchise since.

So that’s a great thing. The bad thing is he’s dead. You tell me how they get out of that one. I want to ask Dave, “How would you get out of it?” As for a great Bond villain? José Mourinho. You can’t get better than that can you?

David Miliband

President and CEO of the International Rescue Committee (and former primary-school classmate)

Would you have preferred to score a century for England at Lord’s to winning an Oscar?

Unquestionably yes. And I’m serious. Because scoring a century at Lord’s is an achievement. Winning an Oscar is someone else’s choice. It really is. You have no control over winning an Oscar and you’re very aware when you’re sitting there, it’s not up to you. If you’d asked me: “Would you prefer to have made a century at Lord’s or made a film that you are proud of?” I would go for the film. I love the movie I made but the Oscar doesn’t make me love it any more.

Cricket has a long association with writers, particularly playwrights, from Stoppard’s cricket bat monologue in The Real Thing to Pinter’s character names in No Man’s Land. Even Beckett appeared in Wisden. What is it, do you think, that appeals to playwrights about the sport?

David Lydon, teacher, Trinity school, London

I was lucky enough to work with Harold a few times and also play cricket on his team, Gaieties, for years. I never played with him, he was the umpire, and his way of turning down on appeal was to say, “Don’t be so fucking stupid!” As opposed to “not out”. And Harold told a story about sitting with Beckett at Lord’s when he was a young playwright – and obviously, Beckett was his hero as a writer – and looking across the ground and saying: “Sam, isn’t this wonderful? Here we are at Lord’s, Ted Dexter, sun in the sky, pint of beer. Makes you glad to be alive, doesn’t it?” And Beckett said: “Well, I wouldn’t go that far.”

I think it’s a game you can lose yourself in. You’re both engaged and observing at the same time, you’re both in and out. And it’s partly a meditative game. It’s not a football match, which demands 100% concentration all the time. You have long periods where you drift. And some of my happiest hours have been spent standing on the boundary of cricket matches both engaged in the game and not. Maybe there’s something in that.

How many trumpets are in your house? Is one of them a Bach Strad 37?

Ex-trumpet player, Brussels

There’s probably about six or seven trumpets. My wife obviously is a trumpeter, and a brilliant, brilliant musician and an extraordinary person and hates practice. And so doesn’t have a go-to practice space in the house. As a consequence, she leaves trumpets in all sorts of odd little areas. So you’ll go into some room and in a corner will be a little trumpet just waiting there because she happened to be practising there. And everyone in the family just gives them a wide berth. It’s a little bit like having a number of pets in the house and none has their own kennel. But it’s a wonderful thing to live with a musician who’s playing beautiful music all the time, even when she thinks it’s not so beautiful. It is.

Armando Iannucci

Writer and director

Among other things, Empire of Light is a celebration of the local cinema as something that sits at the heart of a community. It’s set in the 1980s, but today cinemas, whether independent or multiplex, are struggling to recover from both the pandemic and the rise of streaming. What do you think local cinemas can do to attract a wider, and younger, audience, and keep them coming?

A lot of cinemas are doing the right things now: they’re making it an event for an audience. My local cinema, the Everyman in north London, is a joy to go to. It’s well run. The technical aspects of the way a film is projected and screened are perfect. There’s a human touch; you’re welcomed. The larger cinema chains are struggling, because it is impossible to give that human touch. The multiplexes are in a battle, and that’s no news to you: hasn’t Cineworld just announced bankruptcy? So I think it’s twofold. It’s the cinemas themselves, but it’s also the film-makers being up to the challenge to make movies that demand to be seen on big screens. And for that you need a kind of level of visual and technical ambition that makes it hard for an audience to feel like they’re getting the real thing if they’re sitting at home.

I did my PhD thesis on you and Paul Thomas Anderson and how you both present filmic fathers; is this a conscious theme of yours?

Toby Reynolds, Bristol, film lecturer/screenwriter

I think it’s an unconscious theme that most of the families in my films – American Beauty, Road to Perdition, Jarhead, even Revolutionary Road – are dysfunctional. So yeah, I’m now aware of it, but that’s what happens is you make a number of films and you look back and you begin to see patterns… Dr Freud.

Daniel Kaluuya

Actor

Does any other discipline (artistic or not) inspire you in your field? If so, how?

Sport. All the time. Operating under stress, tactics, strategy. Directing is not unlike coaching in the sense that every player needs something different: some need to be pushed hard, some people need to feel safe, some people will need to work in their own time, some people need to work to a regimen. Not everyone needs to eat the same diet. I follow Arsenal, as does Daniel, loyally, and have done since I was six. I used to say to myself that one of the few jobs in the entertainment world – if you can call sports “entertainment” – that is as much pressure as directing a Bond movie is managing the England football team. And I wouldn’t mind having a nice conversation with Gareth Southgate about that.

Jez Butterworth

Playwright

I get mistaken for you so often I’ve started signing autographs as “Sir Sam Mendes”. For selfies, I alternate extreme rudeness with alarming levels of warmth. My question is… Have the police been in touch?

[Laughs] How can I answer that? Oh dear. I am occasionally mistaken for Jez, and I am always honoured and feel like, “That is a proper artist.” And my only-child part of me is always rather thrilled to feel that I’ve been adopted as one of the Butterworth brothers. So it’s only good for me.

Tanya Moodie

Actor

Would you ever cameo in your own film?

I do cameo in my films vocally. I am in several movies as a background voice, starting in American Beauty. Or I’m whistling or I’m humming or something. It’s often just timesaving, because you’re in ADR [Automated Dialogue Replacement] and I’m like: “That hum’s not right… Let me go and do the line.” For example, in Spectre Dave Bautista’s character, Hinx, who’s the big henchman, has one and only one word. It’s the last thing he says before he falls to his death – the immortal line, “Shiiiit!” And that’s me, I can now reveal. Poor Dave, he was making another movie, he doesn’t need to be at the end of some remote ISDN line from China or wherever he was shooting to do one word. I’ll do it. Although I’m not actually sure he knows that that’s not him. That’s probably news to him as well.

Naomie Harris

Actor

Your brilliance as a creative speaks for itself, but how do you make time for yourself and honour your personal wellbeing while pouring so much into your craft?

What a lovely thing to say. And secondly, it’s a constant struggle, but I’ve got much better at it in the last seven years since meeting my wife. And if you look at what I’ve done: I’ve done two plays, and two movies in seven years, which, by my pre-2015 standards is practically nothing! But I’ve done The Ferryman and Lehman on stage, and I’ve done 1917 and Empire of Light since the end of 2015. And the balance of my life is vastly improved as a consequence. And I have my wife in large part to thank for that. But also you get older and you get less ambitious and less of a workaholic. And unquestionably in my 20s and 30s, I was entirely addicted to work and it was on to the next thing, without taking a breath.

Micheal Ward

Actor

Sam, you were really good at understanding what we needed as actors to allow us to be free to perform. Like setting the mood of quietness when we needed it most, or having us laugh before takes. Where do you think that comes from?

Micheal Ward, actor

What I love about that is that Micheal thinks I do that for every actor, but I just was doing it for him. I’m serious. Some actors don’t want you to tell jokes because they’re laughing at the beginning of the scene. They can do that themselves. But I wanted to stop him thinking: so when there was a dinner party scene where they’re all laughing, I just told them a succession of terrible jokes before every take. But you learn very quickly there are actors that you need to step back from and actors you need to step towards. Elia Kazan says with some actors you need to lay your hands on them, like a horse, to settle them. And other actors, they don’t want to feel you in their space.

Which Shakespeare play challenged you most as a director?

Sasha, photographer

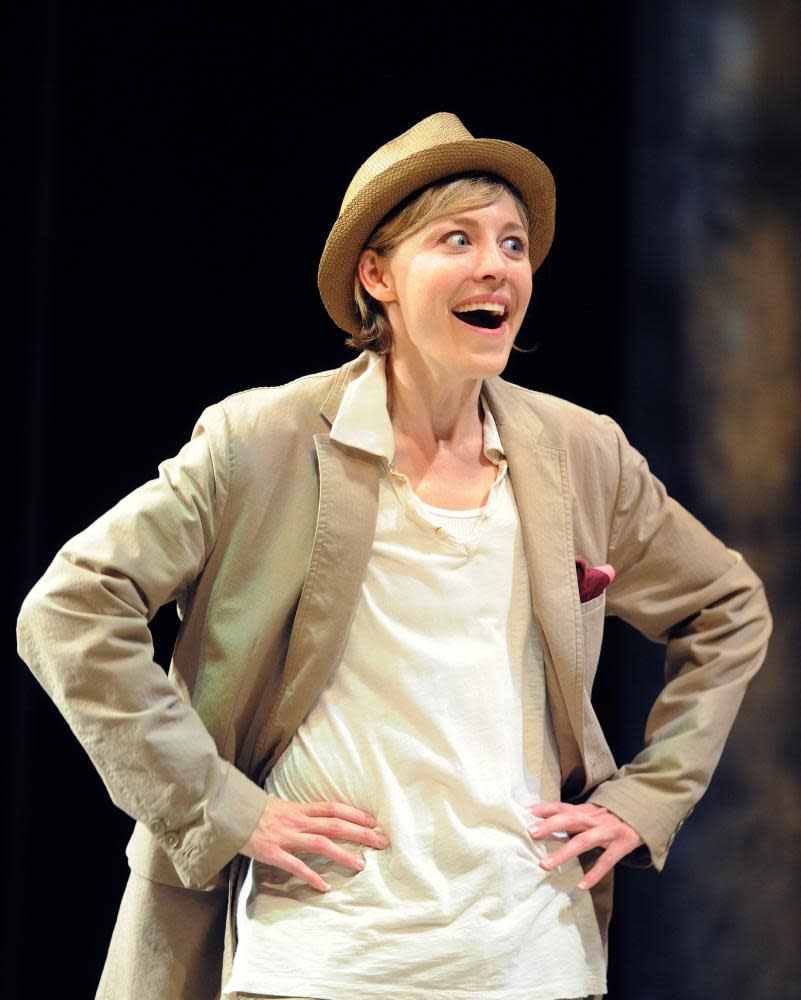

Gosh, well, the one that challenged me the most and I came up short, miles short, was As You Like It [as part of the Bridge Project, 2010]. Couldn’t make head nor tail of it. Terrible. No fault of the actors. I just didn’t have any insight. Sometimes you just don’t know and you think you do and then you get in there and you’re like, “I don’t understand this.”

Your response to the recent Arts Council England funding cuts was characteristically passionate and heartfelt. I’ve always believed that funding bodies require more “coalface workers” than remote middle-managers – would you agree with that? And would you ever consider applying for such a role or would it be too much of a poisoned chalice?

Cathy Burch, teacher, East Anglia

Yes, you’re right about coalface workers. The whole situation with the Arts Council has been appallingly managed. I do think that the Arts Council should have dug their heels in and said: “No, we’re not here to wield the axe on behalf of a bunch of serial incompetents in government.” And I believe that they are incompetent. So I think it was a stupid decision made by people who didn’t and don’t understand the arts landscape. And the Arts Council should have said: “That doesn’t make sense. If you make us do that, we’re going to resign.”

Would I do that job? Never in a million years. And that’s why I feel, on some level, mildly hypocritical even criticising it, because of course, it’s impossibly difficult under a government that doesn’t believe fully in funding the arts.

Roger Deakins

Cinematographer and a regular collaborator

How, and how much, does the story change and evolve over the course of the making of a film?

Well, in 1917, very little. One of the things that I felt was most pleasing for me personally about 1917 is the journey between my head and the screen was the shortest it had ever been. But that was very unusual – normally, I’d say at least 20% of the vision of the film, and the narrative sometimes of the film, alters. The better the movie experience, the less the story changes from beginning to end.

For me, the most frustrating of the movies I’ve made was Spectre, because I didn’t know how it was going to end when I started shooting it. Starting a movie without knowing what the ending is is not advisable. There should be a health warning on the packet: “Do not direct this Bond movie until you have completed the screenplay.” So there’s two examples: 1917 didn’t change at all really, and Spectre which changed out of all recognition.

Run us through your conversation with the Dreamworks people when you told them you wanted to restart the American Beauty shoot after it began badly.

Ben Kay, creative director, LA

Great question. So it was with Bob Cooper, who was head of production. And Bob said: “What do you think of the first two days?” And I said: “Honestly? I really didn’t think they were very good. And I’m glad you asked me because I’d really like to do them again.” And he said: “Is that going to happen a lot?” I said: “No, because everything on those first two days is slightly wrong. Acting’s too big, wardrobe’s too cartoony. I haven’t done the background properly. Camera’s not moving properly. And now I know what I’ve done wrong, I don’t think I’m going to do it wrong again.”

But because I was so honest about making a mistake, he felt more confident than if I tried to defend it. And after that, bizarrely, they pretty much left me alone. Because they could see that it was different. And better, I think. And it was my great good fortune that it was so clearly wrong. Because if it had been slightly wrong, I think I might not have spotted it so clearly.

Given that Kevin Spacey has gone from a must-see to a hard-to-watch for many people, does this taint how you view American Beauty now, or does his character just seem more aligned with reality and therefore more believable?

Sue Harper, marketing, New York

[Long pause] I feel sad… for all the people who’ve been involved in it, and for him. And I don’t have enough information to be able to say more than that, really. And I haven’t seen the film for maybe 10 years. So I couldn’t tell you how it feels. I don’t tend to watch my movies much after they finish, unless you bump into them on telly.

Es Devlin

Set designer

Tell us about the relationship between theatre and film in your practice: do they inform each other?

Very much so. The thing you learn from theatre is rhythm, and getting used to sitting with audiences. They tell you that they’re bored or that they’re gripped. And sometimes you can’t even say how they’re telling you that. But you do become very adept at learning to judge the difference between the silence of boredom and the silence of rapt attention. I came to making films in my mid-30s, having sat for thousands of hours with audiences and in rehearsal rooms, working and crafting two-hour stories that had a particular rhythm. And that informed everything that I do in film. Without that, I don’t think I’d have had a career at all.

What art do you have on your walls at home to inspire you in your downtime?

Michael Hughes, writer, Bedfordshire

I don’t have much art on the walls where I work. I have a lot of books. I find the view out of the window inspiring, which is of a hill with sheep on it, at the moment anyway. I feel music is more an inspiration actually. In terms of unlocking one’s imagination, I find that most of the thinking happens in the car, on my own, when I’m listening to music. One of the great developments of the past few years is podcasts and narrative audio and audio books, I love all that stuff, and that to me is one of my chief sources of inspiration.

How much time is spent between keeping actors happy and doing your best on making a great film?

Justin, US

You learn very quickly, particularly in the theatre, that there is no direct correlation between a good rehearsal experience and a good production. You can have a great time in rehearsals and it can die on its ass when you go out for the first preview. And you could argue one might lead to the other: in that you get too pleased with yourself, too indulgent, everyone slapping themselves on the back. You’ve forgotten that that’s irrelevant when it comes to the audience.

What happens more and more is the urge to make everyone feel like they’re on the same journey at the same time and try to make sure that people understand what they’re part of and where they sit in the whole process. But yeah, I’ve had mostly good relationships with actors, but I could also name you half a dozen people who think I’m absolutely shit.