Salisbury suspects: Russian security services chase for 'leaks' after series of intelligence blunders

The three weeks since Britain identified the men suspected of poisoning former double agent Sergei Skripal have been miserable ones for Russia’s intelligence agencies.

First came the RT interview and Alexander Petrov and Roman Boshirov’s much-ridiculed cover story. Few in Russia, let alone the west, believed the fable of two supposedly gay men, drawn to a sleepy English town by a gothic cathedral and its 123m spire.

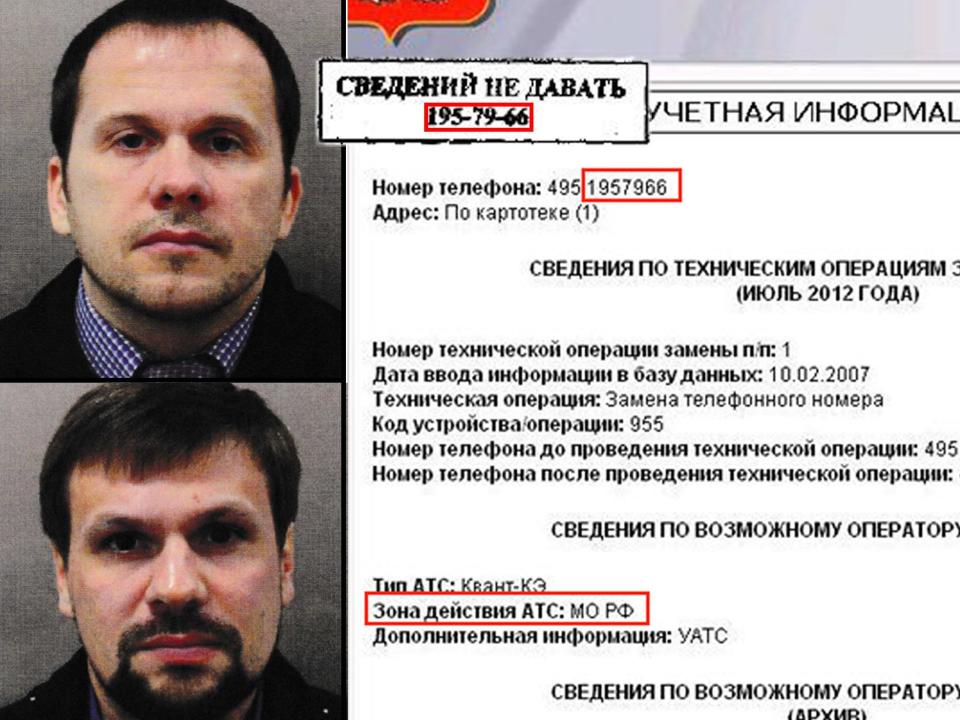

Things got worse once open-source sleuths like Bellingcat and The Insider got to work. Their investigations revealed that the classified passport details of the two men led directly back to the country’s military intelligence service (GRU). What was more, several dozen GRU agents appeared to been issued passports in numerical sequence. It was enough to check travel records to identify probable intelligence officers. Some publications have already begun to do so, with largely unclear legal consequences.

On Tuesday, however, Russia’s security agency, the FSB, appeared to be making a belated effort to limit the fallout. According to the Rosbalt information agency, agents had begun to conduct urgent searches at the Interior Ministry – the source, they believe, of the passport information that found its way to Bellingcat.

Bellingcat’s founder Eliot Higgins told The Independent that the reaction “spoke to the authenticity of the material” they had published.

“Russian officials try to attack Bellingcat’s work publicly, but privately it appears they’re taking it far more seriously,” he said.

Immigration and passport data have always been fairly easy to access illicitly from vendors at certain city markets or via online agencies. One detective agency, still accessible online at the time of writing, offers data from the official Rospasport (passport) and Peremescheniye (cross-border travel) databases. Detailed phone records are available to those even more curious. Prices range from 5,000 to 40,000 roubles (£58 to £462), with discounts of up to 40 per cent for “especially loyal customers”.

Up to now, Russia’s security services have not made any serious attempt to close down the data black market. This is despite its proven role in the criminal underworld and in providing intelligence for the murders of prominent public figures like Boris Nemtsov.

But that may now be changing. Emailed requests for more information, sent by The Independent to several agencies, went unanswered by the time this article went to print.

According to a security agency source quoted in the Rosbalt report, the Interior Ministry officials who leaked the information may not have been aware of the nature of the documents they were selling. It was a simple “transaction”, he said. Nonetheless, “serious consequences” awaited those who had allowed such a leak.

While apparently confirming the passport application forms were genuine, the source also insisted that the conclusions being drawn by journalists about the Salisbury suspects were “fabrications” and “guesses”.

“You can turn any form upside down and turn any person into whoever you want them to be,” the source is reported as saying, “but the published information contained personal information that should not be in the public domain”.

The passport forms of Petrov and Boshirov contain no information beyond the date of passport application (2009), a “secret” stamp, a phone number apparently connected to the Ministry of Defence, and the number of a passport office (FMC 770001) known to be used by Russia’s security services.

‘In any normal country, a disgrace like this would trigger a full parliamentary inquiry,’

Gennady Gudkov, opposition politician and former KGB officer

So far, there is little sign of a crisis within Russia’s security establishment – despite the scale of the apparent blunders.

“Obviously they are worried about a whole series of reputational and organisational lapses, but there is definitely no sense of panic,” said Valery Solovei, professor at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations. “The mistakes they made talk of a system in degradation, though that was already clear 10 years ago when Litvinenko was killed.”

Gennady Gudkov, an opposition politician who worked in the KGB’s counter-espionage section between 1982 and 1993, told The Independent that he did not recall an intelligence blunder of this magnitude being committed before.

The issue was not so much a lack of professionalism, he said, as “moral and ethical decay” that had entered Russia’s security agencies since the 1990s.

Soviet agents had certainly carried out assassination missions in African countries, he said, but they “stopped short of attacking great powers”.

“Now, it seems that military intelligence is revelling in ever more crazy operations – and it is doing so with the understanding they have the approval of those at the very top.”

Mr Gudkov said he still found it difficult to understand how Vladimir Putin could have given a green light to this specific operation. But there was a still case to be answered.

“In any normal country, a disgrace like this would trigger a full parliamentary inquiry,” he said.