What it was like to sail aboard the RMS St Helena’s final voyage

The word “lifeline” is one too often bandied about and devalued; but, in the case of the Royal Mail Ship St Helena, it is entirely appropriate. In fact, she is its very definition.

For 27 years now, since her shiny new hull first slipped through the murky waters of Cardiff Bay in 1990, the RMS – or “Betty Blue Bucket”, as she is affectionately called – has plied the mid-Atlantic, nurturing Britain’s remote overseas territories and linking them to civilisation. Central to these rocky outcrops is the island of St Helena: sea lashed, cliff bound, the one-time darling of the Honourable East India Company, and haven to over 4,000 “Saints”, as locals are known.

The RMS is the last of her species, the only working royal mail ship left of a fleet that used to string together the distant strands of empire. Two other ships carry the title, but it is only honorary.

The RMS was purpose-built by the UK government, a 105m vessel able to carry 7,000 tonnes of cargo and passengers, all cocooned in a dark blue hull with white topsides, and crowned by a mustard yellow funnel bearing a golden merlion.

Now, however, the fatal day has come. St Helena, formerly the second most remote island in the world, has built an airport, a masterpiece of engineering bedevilled and delayed by topography, and after a two-year reprieve the RMS has completed her final voyage.

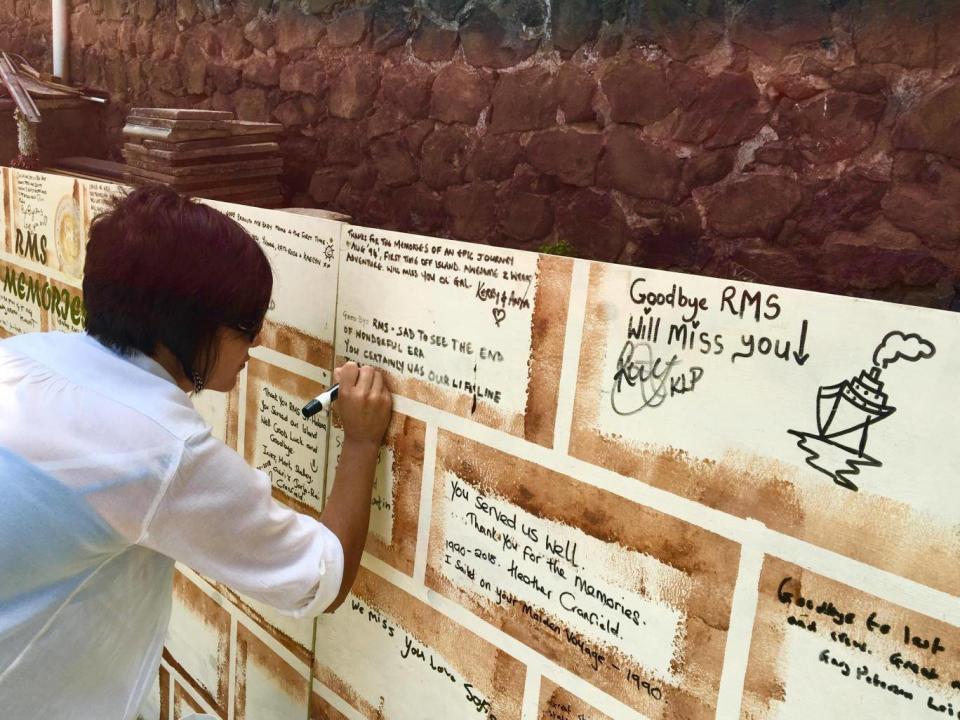

To the Saints, she is much more than a ship. This is the end of a love affair.

How many other ships have commanded a public holiday to celebrate their life and mourn their parting? If that sounds too dramatic and anthropomorphising, it isn’t – because the RMS really does hold special meaning for every islander.

She has fed and clothed them, employed them, taken away the sick to be healed, and the young to work and be educated. She has repatriated the remains of the departed and returned new mothers with their mewling infants. She has delivered boats and cars and livestock, seed for the land and letters from loved ones. She has been a microcosm of humanity in all its forms, a floating community.

And she’s family: a Saint ship crewed predominantly by Saints and captained by Saints. On every departure day, outside Jamestown’s fortified wall and alongside the Georgian wharf buildings, Saints would gather, bid fond farewell to friends and relatives, and shed tears in abundance.

How does an island say goodbye to such an intrinsic part of its existence? It began soberly enough with an ecumenical Service of Thanksgiving in St James’, the oldest Anglican church south of the equator, replete with rousing hymns and touching moments, such as when Captain Adam Williams handed over the ship’s Bible to Bishop Richard Fenwick.

The day before her final departure, the public holiday, was less sober. The sun shone hot as stalls sold memorabilia and islanders packed the decorated seafront, downing drinks and munching burgers. Darkness fell, and while the RMS sat anchored in the bay, magnificently ablaze with light, the officers and crew shed their uniforms for costumes and dresses to entertain the crowds with a riotous pantomime, “The Final Act of Stupidity”. The evening culminated with a symphony of fireworks over nearby Munden’s Battery, dancing and a live band.

From church to stage to ceremony – and her parting day. The immaculately uniformed crew paraded to the wharf landing steps, preceded by bugling scouts; the captain – resplendent in spotless formal whites – received a serpentine 27 foot flag representing each year of service; and the company flag was lowered to a piercing fanfare with choirs singing Now We Say Goodbye and The Last Farewell.

I was in the captain’s launch as it looped through the moorings in the bay, leading a flotilla of assorted fishing vessels, yachts, inflatables – even an American landing craft. Twin fountains hosed skywards from the cargo barge, and the captain stood surefooted, erect and presidential as he hailed the cheering, flag-waving crowds.

Once on board we sipped glasses of champagne to explosive bursts of confetti and clouds of balloons, the ship covered with signal flags, the unique red-on-white pennant of the Royal Mail whipping from the masthead.

Finally, the RMS weighed anchor, sailed down to the gun batteries of Buttermilk Point, and spun round for a final pass across the bay, penetrating the hills and valleys with the reverberations of her friendly, deep-throated ship’s whistle.

Slowly the flotilla fell back, leaving only the jet skis buzzing around like bees. Beneath the vertiginous cliffs of Southwest Point we paused, obeying maritime law, to lower the excess of flags. Was it providence that we spotted a whale shark off the port bow and were accompanied by an escort of pantropical dolphins? It seemed so. The old lady of the sea kicked in her propellers and turned her bow into the Trades for the very last time: destination, Cape Town. The RMS species was officially extinct.

But if you have a few pennies to spare, a deep mooring and an eccentric penchant for philatelic paraphernalia, your luck is in. She’s for sale.