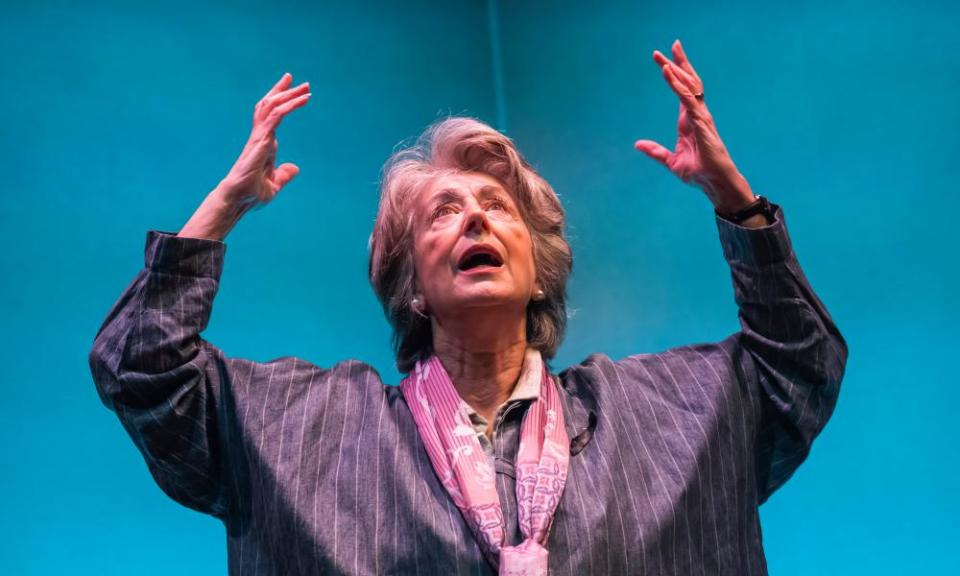

Rose review – Maureen Lipman is magnetic in journey through Jewish 20th century

Rose doesn’t believe in the future. It’s hard to look forward when there’s so much past to contend with. In this memory play, its Jewish heroine sits shiva – mourning for the many dead.

Martin Sherman’s solo play summoning the Jewish 20th century premiered in 1999. Maureen Lipman starred in an online production early in the pandemic – now she gets to spellbind in person. Often goofily physical, here she is rivetingly contained, all restraint and grace notes (though the colourful, overenthusiastic lighting design can make her seem trapped in a lava lamp). She’ll crack a joke then watch us quizzically; chasms open behind the twinkle. Tears fall unbidden, barely acknowledged: Rose’s turn is an unsentimental one.

Lipman’s heroine sounds incredulous at her journey from the harsh shtetl: “If you have your first period and your first pogrom in the same month, you can safely assume childhood is over.” Persecution’s senseless cruelty is a recurrent thread: the Warsaw ghetto and the unyielding postwar British, military ire directed at refugees in leaky boats that still feels all too familiar.

Rose evokes her fervent first husband and then her klutzy second, bringing her from exhausted Europe to the Jewish holiday resort of Atlantic City (“The air smelled of aspirin and chicken fat and suntan oil”). No one there wants tales from the Shoah: Rose’s son and grandchildren eventually leave her world of chopped liver and dybbuks to settle in Israel: “Your shadows are killing us,” they insist. That milk and honey dream also sours – Rose is bewildered by Jews wielding rifles. Fervour becomes fanaticism, leaving her behind.

Sherman (best known for Bent) is a writer of broad brushstrokes; what you hear is what you get. Despite its wry gags (“Jews aren’t visual – look at what they wear”), the play becomes mired in claggy exposition and an episode of blunt whimsy when Rose invokes her first husband’s spirit.

Scott Le Crass’s production suggests Jewish identity as an act of memory, even when recollection is the last thing you can bear. Rose, who always feels like a displaced person, makes the century real by remembering it – she’s her own restless dybbuk.

At Park theatre, London, until 15 October