Robert De Niro, Jerry Lewis and the mutual hatred that made The King of Comedy a classic

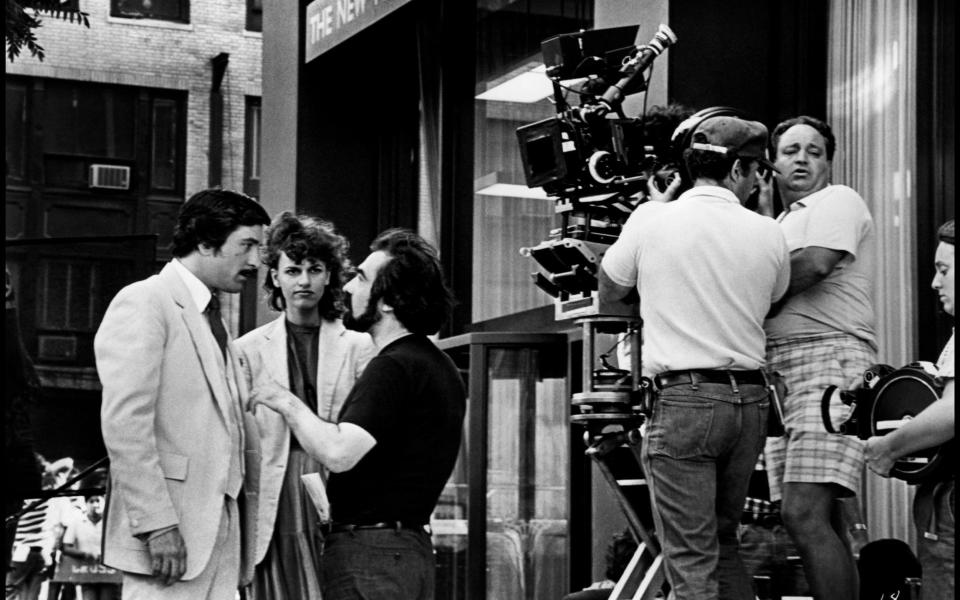

Martin Scorsese was not in a good place. Almost as soon as he’d started work on his latest film, The King of Comedy, he began to have regrets.

The studio wanted him to turn the near million feet of film he’d shot into a hit. But he wasn't ready. Both New York, New York and Raging Bull had struggled at the box office. He couldn’t afford a third dud in a row.

“I got myself into such a state of anxiety that I just completely crashed,” Scorsese recalled in the book Scorsese on Scorsese. “I’d come downstairs from the editing room, and I’d see a message from somebody about some problem and I’d say, ‘I can’t work today. It’s impossible.’ My friends said, ‘Marty, the negative is sitting there. The studio is going crazy. They’re paying interest! You’ve got to finish the film.’”

“Marty got a little caught up in it,” Sandra Bernhard, who played Masha in The King of Comedy, says now. “I think it was uncharted territory for him.”

The King of Comedy was released 40 years ago on 18 February, but by that time Paul D. Zimmerman’s script – about an obsessive fan of a late night talk show host whose fantasies of fame lead him to kidnap his hero and attempt to take his place on air – had been around for nearly 15 years.

Robert De Niro bought the option with the idea that he could play would-be stand-up Rupert Pupkin. The subject matter had been on De Niro’s mind – he had been badly shaken by the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan in March 1981. He talked Scorsese into the director’s chair.

Zimmerman had envisaged Dick Cavett taking the role of Pupkin’s hero Jerry Langford, but Scorsese pursued Johnny Carson briefly before Frank Sinatra’s name was floated, as was Sammy Davis Jr. Orson Welles was briefly in the running too, before being dropped for not being quite showbiz enough.

In the end Scorsese and casting director Cis Corman landed on Jerry Lewis, the rubber-faced stand-up. “We all grew up with Jerry Lewis,” says Bernhard. “He was a big part of the American culture. He was just the eternal adolescent goofball.”

Bernhard was the polar opposite. Before The King of Comedy, she was a regular at the Comedy Store in Los Angeles. Her act was abrasive and innovative, “a post-feminist, groovy, fun, rock-and-roll free-for-all”.

It was her friend and fellow comedian Lucy Webb who pushed Bernhard to go for the audition, having been turned down herself. She improvised a few scenes for a casting director. “And she looked at me and she said, I think you need to meet with Marty.”

Her character, Masha, was a teenager from a wealthy New York family whose obsession with Langford came with a much more violent, sexual charge. “She just seemed like she was kind of lonely,” she says.

Before they worked together, she had only known Lewis’s “very campy” persona. On set, she got to know him better. They stood on two sides of a generational chasm.

“Women were superfluous to him, especially in the setting of working with him as a performer-actor,” she says. “And then you add in the whole idea of the completely new generation of women like myself [and] he couldn't wrap his mind around it. And then the character, of course, just exacerbated everything.”

De Niro was slightly distant, and at the peak of his powers only a few months after winning the Best Actor Oscar for Raging Bull. “He seems distracted,” says Bernhard, “but when you're working with him, it all comes together.”

De Niro had used Method techniques in Raging Bull, and went as far as tracking down his own stalkers. He took one to lunch to ask why he was so fascinated by De Niro. What did he want? “To have dinner with you, have a drink, chat,” the stalker replied. “My mom asked me to say ‘hi’.”

Scorsese had been rushed into shooting a month early as a writers’ strike loomed, and was recovering from a bout of pneumonia. “Physically I didn’t feel ready,” he said later. “I shouldn’t have done it and it soon became clear I wasn’t up to it.”

Nonetheless, the shoot started. Scorsese was “not uptight or controlling” on set, Bernhard remembers, but he might have a quiet word or two between takes, gently cajoling this way or that. While De Niro’s Pupkin craves centre stage, the heart of The King of Comedy is the extended sequence where Masha has the kidnapped Langford all to herself at last.

As Pupkin gets his big shot, Langford is tied to a chair in Masha’s house where she lives out her own fantasy: a quiet, romantic candlelit meal for two, with Masha becoming more and more crazed. Bernhard remembers that “almost all” of it was improvised, and Masha’s ramblings came from Bernhard’s act at the time.

“He [Scorsese] wanted it to be over the top and that was very easy for me at that time to do – intense and crazy – because I guess, I was very young and I was sort of like: okay, great, I'll do it. It would be much harder for me to access that part of myself now, I think.”

Later Scorsese would look back on the shoot as “very strange”. A single scene where Pupkin takes his girlfriend to Langford’s country house under the pretense that they’re staying with him for the weekend took two weeks to film. Opposite De Niro, Lewis watched him deliberately slow things down.

“I watched him feign poor retention just to work a scene,” Lewis told author Andrew J Rausch in 2010. “I watched him literally look like he couldn’t remember the dialogue. He knew the f---ing dialogue. It was masterful.”

Lewis also remembered De Niro deliberately trying to provoke him with anti-Semitic insults while in character. The abuse was, Lewis said, disgusting. He flew into a rage, unaware that the camera was still rolling.

“I don’t know if I said anything anti-Semitic,” De Niro told Playboy later. “I might have said something to really bust his balls.” When Lewis saw the performance he gave while fuming with De Niro, he softened. “He gets you so involved with what you are doing that you find yourself doing things you didn’t know you could do,” he said in 2010.

Bernhard and Lewis’s relationship was dysfunctional too. Lewis mocked Bernhard on set, calling her “fish lips,” and Bernhard flagged it up to Scorsese. Chastened, Lewis brought her a typewritten note on yellow legal paper bearing a short apology. But by the end of the day it had gone missing.

“I don't know if somebody came and cleaned up the room and took it,” says Bernhard now, “but it was my imagining that Jerry Lewis sent somebody in to take it back so that there would be no proof that he had ever apologised.”

Content while the cameras were rolling, Scorsese found himself at a low ebb afterwards. His marriage to third wife Isabella Rossellini, daughter of Roberto Rossellini and Ingrid Bergman had broken up, leaving him “flat and crazed,” as he later recalled. He couldn’t face looking through the reams of footage.

“There were 20, 25 takes of one shot, 40 variations on a line,” he told Peter Biskind in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. “For the first two months, I just couldn’t do it.”

At length, he and editor Thelma Schoonmaker finished their work. But the box office returns on a $19 million budget were sluggish. It limped to $2 million, and Twentieth Century Fox decided to pull the film from cinemas after a month.

“Basically it was, screw you, forget the picture,” Scorsese told Biskind. “I realised at that point nobody cared, and that was when I really understood that the 70s were over for me, that the directors, the ones with the personal voices, had lost. The studios got the power back.”

The director was distraught. “He was afraid he would always be the critics’ darling but the American public would never love him,” his friend and collaborator Sandy Weintraub said later.

The King of Comedy marked the end of an era for Scorsese. Scorsese retreated to low-budget comedy-thriller After Hours while struggling desperately to make his passion project, The Last Temptation of Christ. But in the last four decades The King of Comedy’s stature has grown.

“It was kind of insane, but it was kind of brilliant,” says Bernhard. The idea of a beloved celebrity being abducted by obsessive fans was, she thinks, “at that time a little bit uncomfortable I think for the American public – it seems like child’s play now, but back then it had a little more punch to it”.

As the nature of the fame economy has changed, and social media collapsing the distance between the famous and their fans, the film has felt more and more pointed.

“People have a much more sophisticated insight into the entertainment business and that fine line between people being fans and friends, and enemies at the same time,” Bernhard says. “I think fans love their entertainers, but they resent them and it's weird. The closer a fan gets to the person they love, the less they love them. It's a strange phenomenon.”