Robert De Niro And Al Pacino Have Unfinished Business

An Al Pacino anecdote is something to witness. They ramble, ebb, and occasionally perform three-point-turns mid-sentence. Take the one he tells about meeting Frank Serpico – New York City cop and legendary anti-corruption 'lamplighter', in Serpico's own words. The scene: a house in Montauk, at the tip of Long Island, prior to Pacino taking the character on for Serpico.

"We were sitting on the deck talking and Frank said to me, I said to Frank, why did you finally, why did, why didn't you just take some of the money they were offering you? And, and just be, just, you know, continue what you're doing, give it to charity, you know? Just, just, do something. You're going through this hassle and all. He was looking at me, as I was saying this. And finally – "

He turns to Robert De Niro. "I don't know if I ever told you this. Did I ever tell you?" There's a pause. De Niro shakes his head. Pacino goes on.

"I looked at him and he looked at me and he was saying, he says: 'Well, if I did that Al – who would I be when I listened to Beethoven?'"

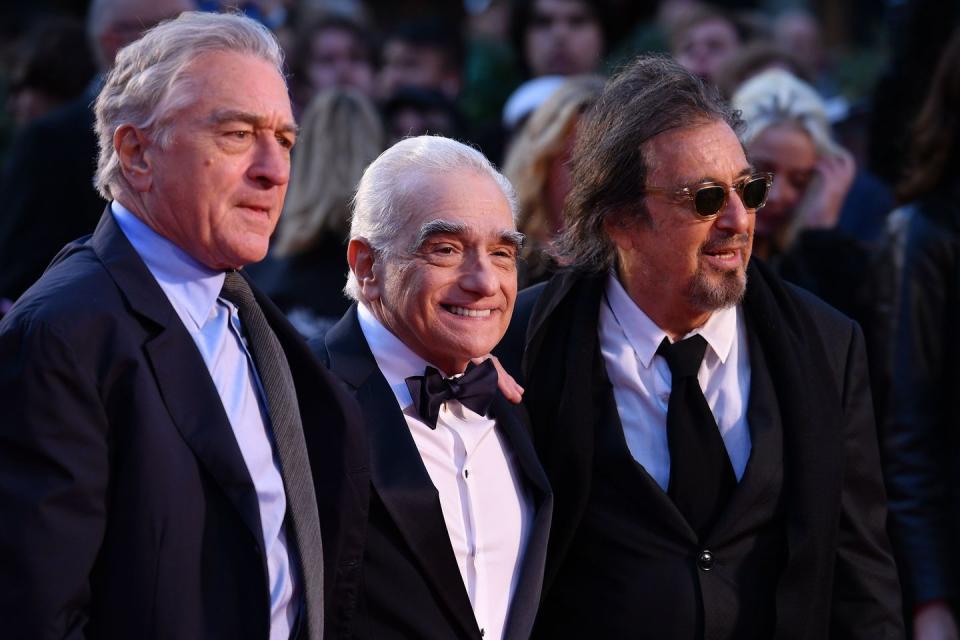

You sense that Pacino's always searching for that kind of unexpected thread. He found a similar way into Jimmy Hoffa, the union kingpin and organised crime boss who he plays with relish in Martin Scorsese's The Irishman. (De Niro is the titular Irishman, Hoffa's longtime heavy and confidant Frank Sheeran.) Despite Hoffa's reputation for political skullduggery, he was also, Pacino points out, a prison reformer, and backed Martin Luther King while simultaneously fighting the Kennedy administration.

As he does on screen, De Niro the interviewee offers a counterpoint to Pacino's soliloquies. He doesn't speak in diversions. When he feels he's said enough, he stops. On average, his responses last about a fifth as long as Pacino's. But what could seem like offhandedness masks a deep well of passion for a film it should have been impossible to get made, but which he was instrumental in forcing over the finish line.

In Scorsese's telling of the genesis of The Irishman, De Niro came to him with a book by Charles Brandt, an investigator whose interviews with Sheeran, before he died, became the book I Heard You Paint Houses. De Niro devoured it on the set of his first film as director, The Good Shepherd, then tried to talk his old friend through it. Scorsese could see De Niro was "really emotionally involved" with Sheeran: "So much that he couldn't describe – he couldn't really speak." So what was it that moved him so much?

"I believed everything that he said in the book: I can tell by the dialogue, I can tell by the situations the whole milieu, the whole feel was real," De Niro says. The scale of the personalities and their purported influence on the early Sixties was another pull: The Irishman suggests that the Mafia was involved in John F Kennedy's assassination, as well as Hoffa's disappearance in 1975. Officially, these are unknowns. But Hoffa's political and cultural presence in the early Sixties can't be understated.

"Al was saying, he's like the Beatles, you know – so famous, like Elvis Presley," De Niro says. "That size was important for this story, told in such a small, intimate way."

Then, suddenly energised: "And the end – it's about dying."

Mortality is front and centre in The Irishman, both in the de-ageing of its stars and in the creeping sense that this is the final time that these Legends Of Cinema will share a screen in a picture directed by fellow Legend, Martin Scorsese. After all, nobody really thought the Scorsese-De Niro-Pesci axis would come together again for a gangster film, and not just because Pesci had quit the industry in 1999. But the truth is more ambiguous.

For one, De Niro used precisely that logic to pry Joe Pesci out of retirement. "We wanted Joe to do the movie and I would say to him: 'Come on, let's go – it's the last time, probably, that we're gonna be able to do something like this, you gotta do it.' And so we went back and forth, but he loves Marty, respects him immensely of course, and cares a lot about me."

Then again, De Niro isn't saying no to another Scorsese gangster film personally: "I don't know. I mean, you never know until there's no more, so I would never say no to anything."

That The Irishman is Pacino's first appearance in a Scorsese film, in a career that spans half a century, is bizarre. And not just to film fans. "I gave up on the chance," he says. "We had started a few times. You know, it's in the very nature of what we do, the business, whatever it is. Things start and people go in different directions. You know, I didn't make movies for about four years. So you know, these these things go on these hiatuses, et cetera. But I did work on a couple of projects with Marty, it just didn't turn out. So I'm very grateful that I'm working with him now. And hope one day to work with him again." He pauses, then looks up and smiles. "He is great."

Hoffa, who ascended to the pinnacle of the US labour movement through charisma and violence in equal measure, is a part which gives Pacino a chance to twinkle and charm, but also license to rage with operatic fury. There are some Glengarry Glen Ross-level eruptions in The Irishman, although that isn't the Hoffa that Pacino personally remembers. "I knew about Jimmy as a kid, because he was in the news and he had an image that was kind of almost shady, but also very positive."

De Niro would watch his co-star as he paced the set with earphones in, and wondered what he was listening to. "I was listening to Jimmy Hoffa speak," says Pacino.

The two actors were kids when they first met on 14th Street in New York, between First Avenue and Avenue A. Pacino's then girlfriend, Jill Clayburgh, met De Niro while working on Brian De Palma’s The Wedding Party, in 1963. "He wasn't, like, forward or showy," Pacino says. "He just had a tremendous charisma."

The Irishman transports the pair back to their youth with groundbreaking de-ageing technology, which wipes the decades away. Though De Niro does his usual joke about it adding 30 years to his career, there's concern there, too. With James Dean set to be digitally resurrected more than 60 years after his untimely death, his worries are more than techno-paranoia.

"I mean, who knows when they get to a certain point with artificial intelligence and whatever else comes along, that our images will be propelled in such ways that will be younger or this and that. What do you do? How do you own those rights, property rights? What you will? If they distort them a little bit – well, they even do that now – then do you not have the right to claim that it's you? It's infringement of some sort."

He could act forever now, though. He smiles. "As long as I get residual."

Eventually we get onto the tension between The Irishman’s cast, aesthetic and director, and the fact that most people will watch it at home on Netflix.

"When you see a film in a movie house, it's another experience," Pacino says. "Whatever the level of the film is, you're there and you're engaging. When you're watching a film. It's going to be interesting to see what happens to The Irishman when it's being viewed at home, on a big television screen because the mere fact that you can stop a film at any time, make a phone call, you know, and break away from it is another experience. I don't see how you can compare it. I too like to watch films at home, you know, I do, but I realised that it's a different experience. You can't have that. So hopefully what we're trying to do, and I could speak for you, right, about this?"

De Niro raises his eyebrows and pulls the corners of his mouth down in the time-honoured manner. Pacino goes on.

"What we're trying to do is see that we have theatres in the cities, even an arthouse somewhere and it's playing, you know, so that they have the opportunity to go to see it."

He's back in his storytelling rhythm now, this time about recently rewatching his performance in Palm d'Or winner, Scarecrow, for the first time since its 1973 premiere.

"Quentin Tarantino has a theatre in Los Angeles where he just shows 35-millimetre movies, so. And I went to see this film, Scarecrow. I haven't seen it since it opened but I didn't have much time. So he said to me, 'Well, come on, just look at the opening.' And I went saw that film, and you had Jerry Schatzberg, who was a great photographer, directing it, and you have Vilmos Zsigmond doing the cinematography. To sit there and watch it on 35, that is what changed everything. And I became converted at that point as to wanting more films. Because if you don't see them on 35, you're deprived a little bit of something, of an experience."

Most people won't get that experience with The Irishman. Netflix stumped up almost $160m to fund a Scorsese-De Niro passion project that runs almost three-and-a-half hours, because no other studio would. It's opening in a handful of cinemas, for a handful of weeks. But if you can, you should find one. This could be your last chance to luxuriate in the work of four of 20th century cinema's last titans. They deserve to be seen in a cinema.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

You Might Also Like