Remember when Bond and Doctor Who were Geordies? Our Friends in the North is as relevant as ever

Two very different Tyneside dramas this week. One with a reputation so towering it could easily have intimidated its cast; the other with one cast member so starry he might have overshadowed the rest.

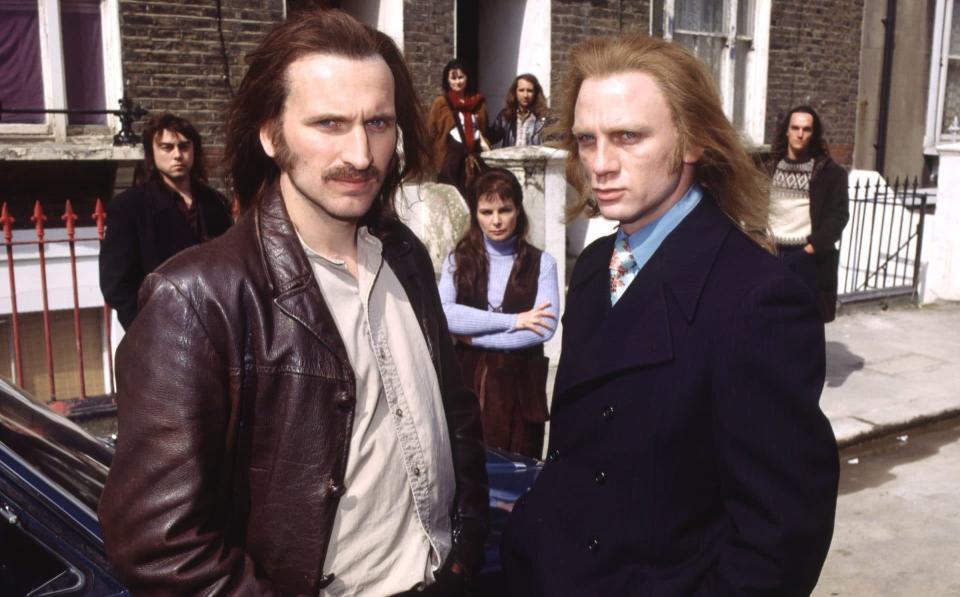

Our Friends in the North (Radio 4, Thursday) hardly needed an introduction. One of the most fêted TV drama series of the 1990s (one that propelled its then barely known cast – Daniel Craig, Christopher Eccleston, Mark Strong, Gina McKee – to national and international fame), Peter Flannery’s epic tale is an unflinching and unflattering snapshot of Britain between the Wilson and Thatcher years, as seen through the eyes and lives of four working-class northerners.

Back in 1996, its bitter tale of political failure, criminality and corruption caught perfectly the zeitgeist of a hope-hungry electorate that swept Tony Blair’s New Labour into power just over a year later.

Adapting it for radio, Flannery appears, sensibly, to have taken a light touch approach, reproducing the existing nine-episode structure more or less exactly. (That said, there will be a 10th episode, written by Adam Usden, to take us up to the present day.) The only real change in the opening episode was the pushing forward of Mary (Norah Lopez Holden, leading the cast of newcomers) into the role of narrator – a clever way to guide the audience into the story aurally, and to make her put-upon character more relatable for contemporary audiences.

If anything, Flannery’s superb writing is even more in evidence without the visuals. His crackling swordplay dialogue keeps the atmosphere electric: his ability to touch upon the universal makes his characters instantly recognisable from the outset – Nicky (James Baxter), the political one, blinded by idealism; Tosker (Philip Correia), the chancer/lothario; Geordie (Luke MacGregor), the abused boy acting out in reckless behaviour; and Mary, the good woman doomed to squander her gifts on feckless men. It’s all still there, a touch more compressed and polished for audio – and brilliantly realised by Melanie Harris’s spot-on production.

Above all, though, neither the intervening years nor the adaptation to radio, seems to have blunted its sharp edge. Indeed, even though it starts out in 1964, it seems to have just as much urgency and relevance now. Who would have thought that a drama series excoriating compulsive-liar politicians, corrupt and misogynistic police officers, and shoddily built death-trap tower blocks could have any relevance today?

Geordie voices also dominated in I Must Have Loved You (Radio 4, Saturday), a 90-minute musical drama by veteran writer Michael Chaplin (creator of TV’s Monarch of the Glen). The big draw here was the musician Sting, who not only provided the music but also took top billing as the late lamented “Newcastle blues legend” Vince Doyle – a man whose troubled past haunted everyone who loved him.

Chaplin and director Eoin O’Callaghan have worked on a radio play with Sting before, South on the Great North Road, and this felt like a proper collaboration. The convoluted, sentiment-heavy storyline focused on Vince’s more musically talented daughter Jess (Frances McNamee), who, having given the world a one-hit album (a mix of familiar and well known Sting songs such as Shape of Your Heart, Fragile and Hounds of Winter) disappeared in 1997.

When a woman turned up asking the Doyles questions 25 years later, it stirred up painful memories. Or an excuse, at least, for them to rake over a row between Vince and Jess, and her behaviour towards her guitarist Malc (Deka Walmsley) and manager Tommy (Stephen Tompkinson).

For a drama whose two main characters were either dead or/and missing, it worked surprisingly well. Sting’s acting skills were, thankfully, not overstretched as a ghostly one-man chorus commenting on the action. Missing star Jess rather conveniently turned up – mainly, it seemed, to help tie-up the ever more unwieldy plot. And if the mood was about as lyrically mournful as your average Sting song, Chaplin’s insistence on making all his characters “nice” – as if no one from

Newcastle could have anything but good intentions, however misunderstood – at least kept it from dipping any lower.

A please-everyone happy ending didn’t make for a great denouement. But sometimes the journey matters more than the destination. And, for all the disbelief suspending required, I quite enjoyed I Must Have Loved You. Especially the music and the gorgeous singing of McNamee, whom one could easily believe, with a bit of luck behind her, might once have made a hit record that mesmerised the world.