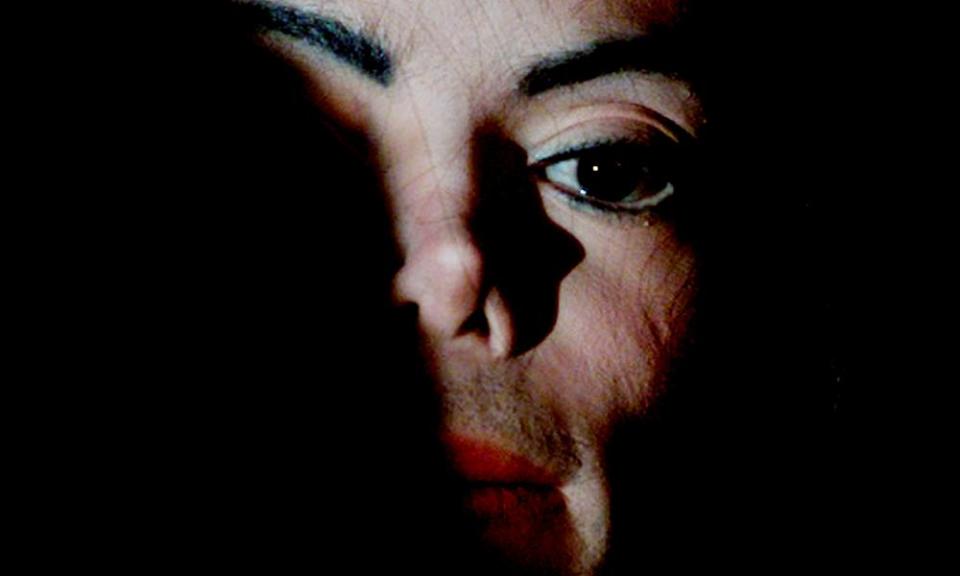

The Real Michael Jackson review – how did he get away with it for so long?

If you keep wondering what to think about Michael Jackson’s complicated legacy – is it OK to play Billie Jean at a party? Do you have to switch radio stations if Smooth Criminal comes on? – imagine how Jacques Peretti feels. He has made three films about the pop icon in the past 15 years and in this, his fourth, he aimed to build the fullest picture yet. But how many of us are brave enough to confront that picture?

The Real Michael Jackson (BBC Two) comes just over a year after the broadcast of HBO/Channel 4’s Leaving Neverland, a gruelling, four-hour documentary built around the detailed accounts of two men, Wade Robson and James Safechuck, who say they were sexually abused by Jackson as children. Peretti’s film was initially billed as a rival Jackson film, but in the event, it’s much more like an unofficial sequel; a film that could not exist if Leaving Neverland hadn’t cleared the media’s hagiographic haze, but which also provides necessary context on the huge fallout from Jackson’s 2009 death.

The Real Michael Jackson has much more in common with Louis Theroux’s 2016 Savile film, in which the newly sombre documentarian confronted his own journalistic failures and berated himself for not doing more to tackle a high-profile abuser who got away with it for so long. Didn’t Jackson also “hide in plain sight”? Peretti makes a compelling case that the pop star deliberately cultivated that “wacko Jacko” persona of the late 80s – Bubbles the chimp, the oxygen chamber, the Elephant Man bones – to provide cover for a truth that was much darker.

Savile’s crimes were not on the same global scale. Peretti details the “Jackson machine”, that small army of private investigators, expensive lawyers and fixers, which swung into gear during his trials, or whenever his reputation was threatened. It is an MO reminiscent of Harvey Weinstein or Jeffrey Epstein. Yet none of these other men had anything like Jackson’s huge international fanbase, which, until uncomfortably recently, included Peretti himself.

“Is he a paedophile? That’s the question that should be asked,” Peretti says ruefully as he (and we) rewatch footage of a younger Peretti interviewing Jackson’s longtime manager Bob Jones (who testified against Jackson in 2005) for one of his earlier films. “And I don’t ask the question. That is a failure … that is a regret of mine.”

In fairness, he is far from the only Jackson-adjacent journalist with regrets for not doing more to quiz Jackson on the rumours. Jackson’s habit of occasionally emerging from his post-Thriller seclusion to attend an awards ceremony arm-in-arm with a 12-year-old, or grant exclusive access to a chosen interviewer, means there is a wealth of footage to scrutinise. Diane Sawyer in 1995 and Martin Bashir in 2003 made the most headlines – even asking him about the allegations – yet it’s the softballs, including Oprah Winfrey’s live 1993 interview at the Neverland ranch, which are retrospectively most creepy (although, to be fair, she did at least ask him about his sexuality). In Peretti’s selected clip, Oprah approvingly notes one of several bedrooms on the property made up for young guests: “You have to be a person who really cares about children to build that into your architecture,” she says.

Could anyone watch all this, especially after Leaving Neverland, and not have profound doubts about the professed innocence of Jackson’s interest in young boys? Apparently so. J Randy Taraborrelli, the celebrity biographer and Jackson’s loyal friend since childhood, continues to believe in Jackson’s innocence and there were a couple of occasions in his interview where you might wish he had been pushed harder. Ultimately though, the non-confrontational strategy paid off in an exchange that is enormously revealing about the nature of denial.

Peretti may not always ask the right question, but he has certainly been asking them of the right people. And now, at long last, the time is also right for genuine reflection. There are astute insights here from a variety of tabloid journalists (admirably candid, to a man) as well as Jackson’s fellow survivor of 70s child stardom Donny Osmond, and Mathew Knowles, talent manager and Beyoncé’s dad. These guys weren’t just there, in the distorting eye of the celebrity storm, they are all too aware of the types of games celebrities played to negotiate media scrutiny.

Is it possible to continue to admire, even enjoy, Jackson’s genius in light of all that we now know? A lot of people remain very invested, both emotionally and financially, in believing that the answer to this question is yes. But the fact that this film touched only very briefly on the evidence of his musical genius is an answer in itself.