Raquel Welch was the best advert for the movies that the movies ever had

Rita Hayworth, Marilyn Monroe, Raquel Welch. Those were the three women on the wall of Andy Dufresne’s cell in The Shawshank Redemption – the figures on the posters that took turns to cover the tunnel that took Tim Robbins’ wrongful convict to freedom after 18 years inside. The Hayworth image was from Gilda, Charles Vidor’s sex-drenched 1946 film noir, in which the actress played the wife of a casino kingpin. The Monroe, meanwhile, was from 1955’s The Seven Year Itch: the billowing dress; the expression caught halfway between embarrassment and delight.

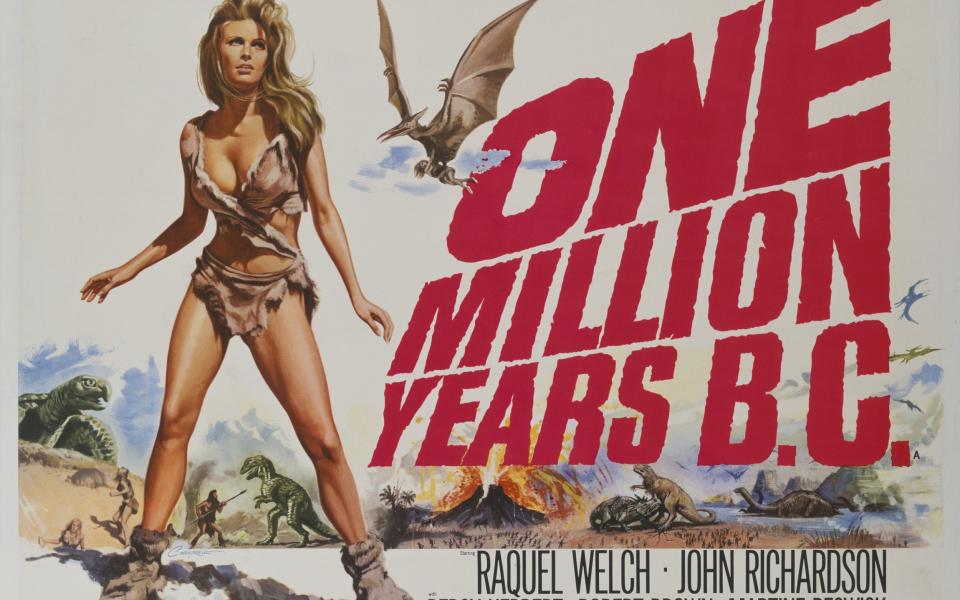

And Welch? She was in the doe-skin bikini from the 1966 remake of One Million Years B.C., the cave girl Loana the Fair One, looking anxiously across a dust-blown prehistoric landscape. Together, these three encapsulated the idea of the sex symbol in mid-century cinema: the women who promised escape, whether their audience was actually stuck in a prison cell or just sunk in the drudgery of everyday life.

The difference with Welch, who has died at the age of 82, is that the poster was the stardom, and vice versa. Monroe had the rich and riveting method performances; Hayworth the ravishing femme-fatale persona. But Welch’s fame was built on that publicity image – a four-foot by two-foot enticement to cinematic pleasures. In that respect, she might have been the best advert for the movies that the movies ever had.

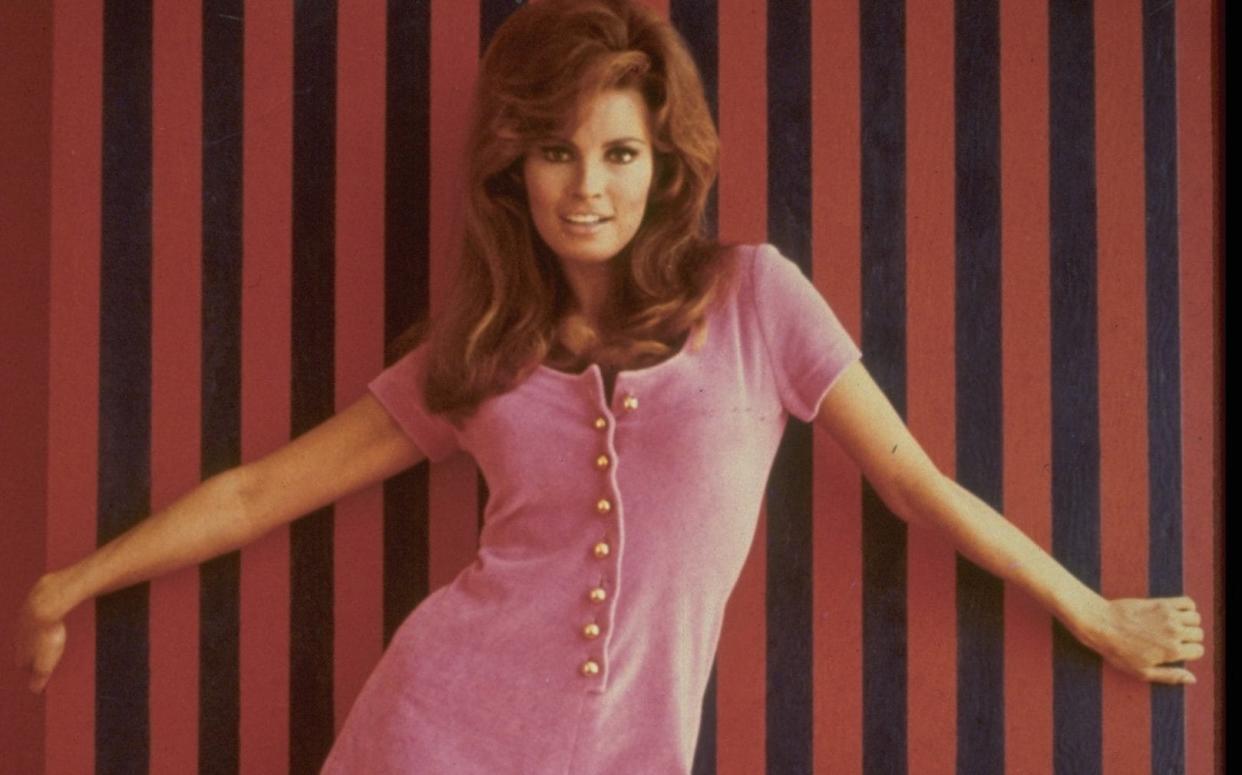

Born Jo Raquel Tejada in 1940 to a mixed-race couple – her father Bolivian, her mother English – she took to the beauty contest circuit in her teens, and got into film via modelling and television bit-parts, taking her first husband’s surname to avoid being typecast as too Hispanic; too exotic.

She was in her mid-20s when the frothy beach party genre was flourishing in Hollywood – an especially good time for beautiful young women to get into the business – and her first starring role came in 1965’s A Swingin’ Summer, as Jeri, one of the original bookish high schoolers to coyly take off her glasses, let her hair fall around her shoulders, and be transformed into a babe in a blink.

True to the form, the role involved multiple bikinis, and in Britain, Hammer Studios sat up and took note. On loan from Fox – with whom she’d just made Fantastic Voyage – she was cast in the production company’s hip remake of a 1940 Hal Roach swashbuckler about photogenic cave-people scrapping with dinosaurs.

Welch famously had just three lines in One Million Years B.C., and her new army of male fans in the weeks and months after its release would probably struggle to repeat a single one of them. Instead, the film – and even more so, the famous production still used to advertise it – made her an instant object of desire, in much the same way that Ursula Andress’s emergence from the Caribbean surf had done for her four years earlier in Dr No.

Today, such a photograph would have to be passed off as arch or ironic. But in 1966, no less a feminist thinker than Camille Paglia described it as an “indelible image of a woman as queen of nature” – while the New York Times’s critic wrote, presciently if also droolingly, “nothing could look more alive and lasting than Miss Welch.”

His instincts proved sound. The perception of Welch as the ultimate object of desire did endure – and reached its logical extreme the very next year by Stanley Donen in his Faust riff Bedazzled, in which she played the embodiment of Lust, slinking into bed in scarlet lingerie beside Dudley Moore after he makes an infernal pact with a devilish Peter Cook.

Her flair for comedy shone through the sex appeal there, as it did in 1969’s The Magic Christian, in which she played a whip-wielding priestess, and even more so in 1973’s The Last of Sheila, the Herbert Ross whodunit in which she gamely played a glamorous but slightly blank starlet. (Stephen Sondheim, who co-wrote the script with Anthony Perkins, had assured her the role was a send-up of the Bye Bye Birdie star Ann-Margret, rather than anyone closer to hand.)

Perhaps her best comic performance came in the first of the two Three Musketeers films she made with Richard Lester in the early 1970s: she played the royal dressmaker Constance Bonacieux, a role that reconciled her gifts for klutzy physical comedy with her considerable sex appeal. It won a Golden Globe – her dining room catfight with Faye Dunaway’s Milady de Winter (weapons include a tiara, a candlestick and a bunch of grapes) is a riot, and among the film’s funniest scenes.

Unfortunately the boldest gambit of her career – playing a transgender woman in the toxically received 1970 adaptation of Gore Vidal’s Myra Breckinridge – didn’t pay off. The film occasionally resurfaces at camp revival screenings, but critical reappraisal remains an unlikely prospect. But she did fine work in a western, 1971’s Hannie Caulder, which Quentin Tarantino credited with inspiring his Kill Bill films.

It’s a pity Tarantino didn’t find a role that might have “reintroduced” Welch in one of his early films, but others were keen to tap into her icon status. In 2001’s Legally Blonde she was the murder victim’s ex-wife, Mrs Windham Vandermark – a neat casting choice in a film about underestimating beauties at your peril. The striking black hat her character wears to testify in court was Welch’s idea: after four decades in the business, she knew the light reflected downwards from its white brim would boost her otherworldly radiance.

Perhaps cinema only occasionally managed to stop gawping for long enough to fully appreciate Welch’s gifts. But whenever it did – and even often when it didn’t – it was all the more dazzling for her presence.