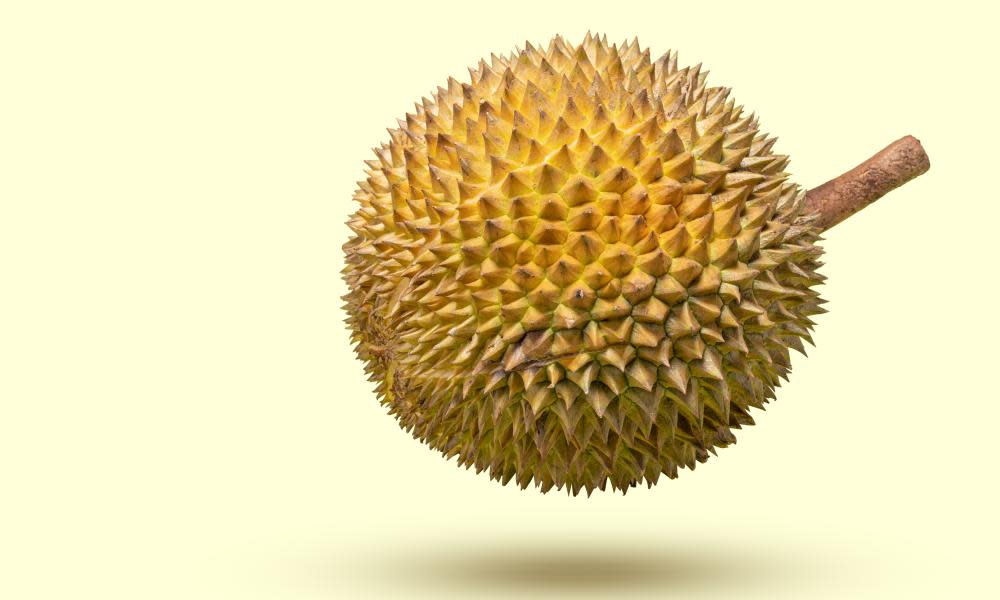

The quest for the king of fruit: like wine snobs, durian connoisseurs are fanatical and devoted

It was already close to 9pm. The race was on. We had exactly five minutes to drive to a secret location before the elderly Amma closed up for the night. We had to pick up our durian.

Let me set the scene: I was in Bangkok enjoying a much-needed catch-up with close family friends during Covid-19 curfew/lockdown. In Thailand that meant citizens must be home by 9pm. It seemed miraculous that the eternally buzzing metropolis obeyed this mandate, but not a vendor, an unnecessary vehicle nor pedestrian was spotted after this hour … except the few belligerent durian hunters. Such is the love for this extraordinary fruit.

This wasn’t my first mission. For this fruit, I have also dropped my familial obligations with a day’s notice and flown from Sydney to far-north Queensland. Durian cannot survive overnight temperatures below 15C, so in Australia it is only grown north of Townsville, and typically harvested from late November to February.

Related: Durian: love it or hate it, is this the world's most divisive fruit?

I was brought to far-north Queensland on distant lead: a friend had a friend whose sister-in-law recently bought an orchard, fabled to have 40-year-old durian trees that had never been sprayed. They forgot to mention that they had also never been pruned.

Two colleagues and I came as a pack, as soon as the sister-in-law called us back to tell us the durians were close to peaking. They needed to harvested, and if we wanted them in Sydney, we’d have to come and sort it out ourselves. Easy enough we thought. Not so.

These trees were already well over 25 meters tall, neglected in the orchard alongside purple mangosteens. Mangosteens and durian are a very common companion planting, since harvesting usually occurs at the same time. In the Thai folkloric tradition, mangosteens should be eaten to minimise the nauseating effects of overindulging on durians, as durians are a heating food and mangosteens are a cooling one. They’re often referred to as the King and Queen of Fruits in south-east Asia.

The grass was chest height and the whole wild orchard buzzed with life – life that wanted to consume us as much as we wanted to consume the fruits. In all our earnestness we’d arrived from the city dressed in shorts, sneakers and flimsy cotton gloves. We were completely defenceless against the swarming green tree ants, wasps, snakes, mosquitos and scorching 46C weather. We ascended the trees with no ropes, no plan and no clue.

We did, however, manage to devise a system. We’d identifying the ripe fruit, then one of us would climb the tree to cut it down – careful to leave the stem as long as possible. Once cut, we’d aim the 5kg fruits at a canvas parachute beneath us; two below holding it up, to ensure each fruit had a soft landing. Otherwise they would have been swallowed in the sea of grass, never to be found again.

Can you see how this is potentially fatal to three novices?

The environment was threatening enough; then add the danger of a spiked cannonball descending at high speed from above and you’ve got the ultimate workplace trust exercise.

All I could think of was the market price of durian – “Ahhh so this is why they’re so expensive.”

Throughout Asia, there are “No Durian” stickers everywhere – they’re commonly sighted in vehicles, hotels, on public transport and in public buildings. Australia has not embarked on a similar project, so the absence of warnings meant we could pick as much as we could load into our rented car, then set off on a two-hour drive to the trucking company we’d found to transport it down to Sydney. Our work complete, with great relief, we jumped into a frigid waterfall to ease our ant bites.

This was all a bit risky. No one we knew had tried the fruit from these trees. Though we knew they were Monthong and Gaan Yao – the two most popular varieties grown commercially in Thailand – we didn’t know how they would taste. We’d leapt into the experience on yearning and blind faith alone.

If you know, you know.

Durian connoisseurs are fanatical and devoted, much in the way wine snobs are. We share this like a secret handshake. Well, actually, it’s not so secret – if you’ve eaten a durian, anyone within a 50m radius will instantly know. The smell is described varyingly, both positively and negatively.

When we’ve had them in our grocery store, Jarernchai in Sydney, shoppers unaccustomed to the whiff have approached staff members with genuine concern, wondering if there’s a gas leak in the building. We all scrambled around urgently trying to locate the leak, and upon finding nothing, it dawned on us the smell was wafting from the durians. None of us who were familiar with the smell thought it resembled a gas leak, though.

Related: Smelly durian fruit forces evacuation of Bavarian post office

I have heard people liken the smell and taste of durian to burning rubber tyres; a young Manchego cheese; and the most heavenly, perfumed tropical fruit. It’s divisive.

I will say this though: no matter how much you think you dislike durian, it is probably due to bad experiences. Once you eat a good one it is undeniably ambrosial. It has a silken, custardy texture that your teeth sink into after you’ve broken the crisp, thin skin of the flesh. Like the initial pop of caviar, you’ll start to understand the fervour. And then you’ll seek out the next godly experience, just to hit that elation again.

Scientifically the fruit is as complex as it gets, with at least nine known edible species, that within them have hundreds of cultivars and wild varieties. Rich in phytochemicals that result in its truly layered aroma and flavour, durian has diverse, volatile compounds such as esters, ketones, organosulfur compounds and alcohols. Its flesh is high in polyphenols, especially carotenoids and betacarotene.

This helps to explain why ripeness matters – the cuisines from areas where they are endemic cultivate durian for harvest at different stages of ripeness. I have eaten them unripe in curries and som tum salad, and as a substitute for potato and green papaya. It’s an excellent stand-in for both.

Passionate discussions are had about how each culture likes to eat their durian at a certain point of ripeness, or the ultimate: when they have fallen naturally off the tree. As with most crops that are grown across many countries, each nation will proudly claim theirs is the best. There are even people who dedicate their lives to durian seeking, such as Lindsay Gasik, who runs the very informative Year of the Durian.

I met Lindsay at a tropical fruit conference that coincided with a durian festival in Chanthaburi, Thailand, where I found myself judging a durian competition. I distinctly remember the winner was a variety called Lin Lap Lae, a petite, odourless fruit with an abundance of rich caramel, vanilla and toffee flavours.

Much of how you like your durian comes down to personal preference, but there are the occasional fruits that have everyone nodding in agreement – yes, this one. This one is the king. Until the next one comes along.

Did we make it to the Amma selling durians on that dark night in Bangkok? Yes, of course we did.

Related: Why does the durian stink? Scientists unravel smelly fruit's DNA

There was no way I was going to miss out on one of her prized fruits, sourced from a mysterious orchard. She’s extremely selective with who she sells to. In select circles she’s known as the “high society durian dealer”. Knowing her gives you more street cred than owning an Hermès Kelly bag.

I smuggled the prized fruit back into the hotel, feeling like I had just won the lottery. Never mind that I parted with a small fortune to get it.