The predator in your pocket: What it's really like to have a stalker

It only took a few days for Hannah to notice the woman wherever she went. But there she was, in the same aisle at the supermarket, standing on the corner outside her son’s nursery, lingering close as she walked into town. She tried to tell herself it was just a coincidence, but it became impossible. One night, after seeing the woman – distinctive, with dark, pointed eyes and hair creeping all the way down her back – she mentioned it to her boyfriend. His face dropped.

The woman who had been following Hannah – the very same woman who, over the next four years, would go on to spy inside her house using binoculars, create 125 fake Instagram accounts, trash her garden, send naked photographs and post a dead rat through the door – was her partner’s ex-girlfriend.

There’s a picture that comes to mind for many of us when we think of the word “stalker”. Perhaps it’s the uncomfortably handsome Joe Goldberg in You, lurking outside floor-to-ceiling windows. Or it might be Alex Gray – the man who stalked Lily Allen for seven years and broke into her home while she was in bed. Both feature a stranger “taking a shine” to his victim and relentlessly pursuing her – and cases like these do happen. But, as Hannah’s story shows, stalking comes in all shapes and sizes – and our misunderstanding of what stalking looks like and who it happens to has a very real human cost. Because this is a crime that’s more common than you think – and it’s growing.

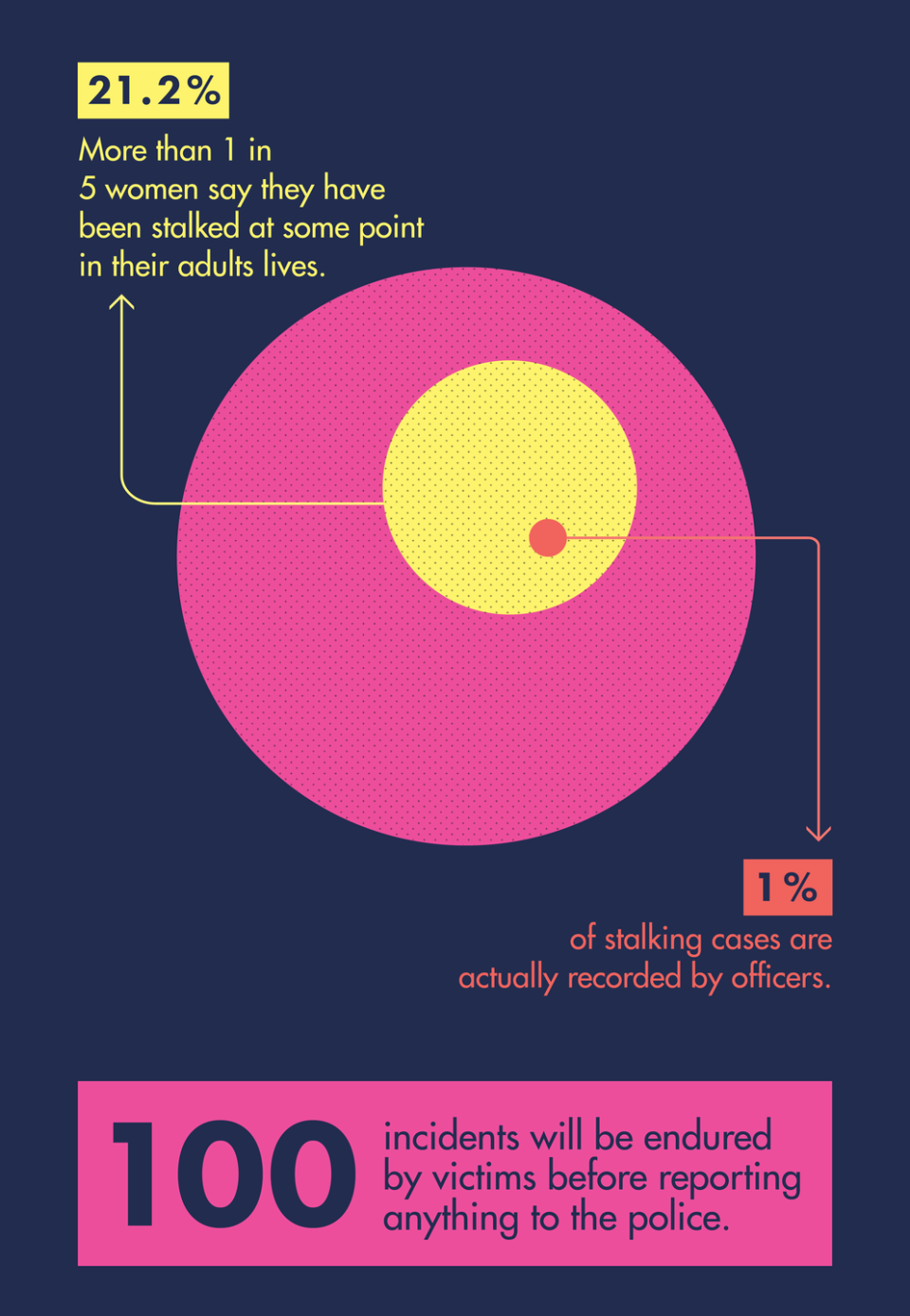

In England and Wales, more than one in five women (21.2%) say they have been stalked at some point in their adult lives, and during lockdown, contact with Paladin, the National Stalking Advocacy Service, increased by 40%. Victims will endure an average of 100 incidents before reporting anything to the police, but even then, only 1% of stalking cases are actually recorded by officers. Violence is not the intention or the end result in every case, but stalking was present in 94% of 358 female murder cases analysed in one UK study. Physical harm aside, being stalked can take an unimaginable toll on a victim’s mental health, fuelling paranoia, stress and anxiety. The stakes are undeniably high – so why does it seem that it’s something of a lucky dip whether or not a victim’s complaint will be taken seriously? And with technology making it easier than ever to intrude in someone’s life, why do these tools seem to be developing quicker than the systems in place to prevent this behaviour? I met those experiencing the crime to find out.

Layla* had left home wearing just the clothes on her back. She was being housed in emergency accommodation several miles away, along with her two children. She’d been warned by social services to leave her partner of two years, Greg*, immediately for their safety. He’d become violent when she told him. With no cooking facilities and little money to her name (Greg had controlled all their finances), 32-year-old Layla scratched around to buy a takeaway. As the night went on, her nerves gradually subsided and she dared to think about a future without Greg’s overshadowing presence.

The next morning, peering out of the window, Layla noticed that her car was missing. Greg, she thought. But how does he know where we are? Days later, the snap of the letterbox made her jump. She went to see what it was, expecting to see a pizza delivery leaflet fluttering to the floor, but was instead greeted with a mound of crumpled red material. It was her son’s football top. A top that had, up until that moment, remained in the house with Greg.

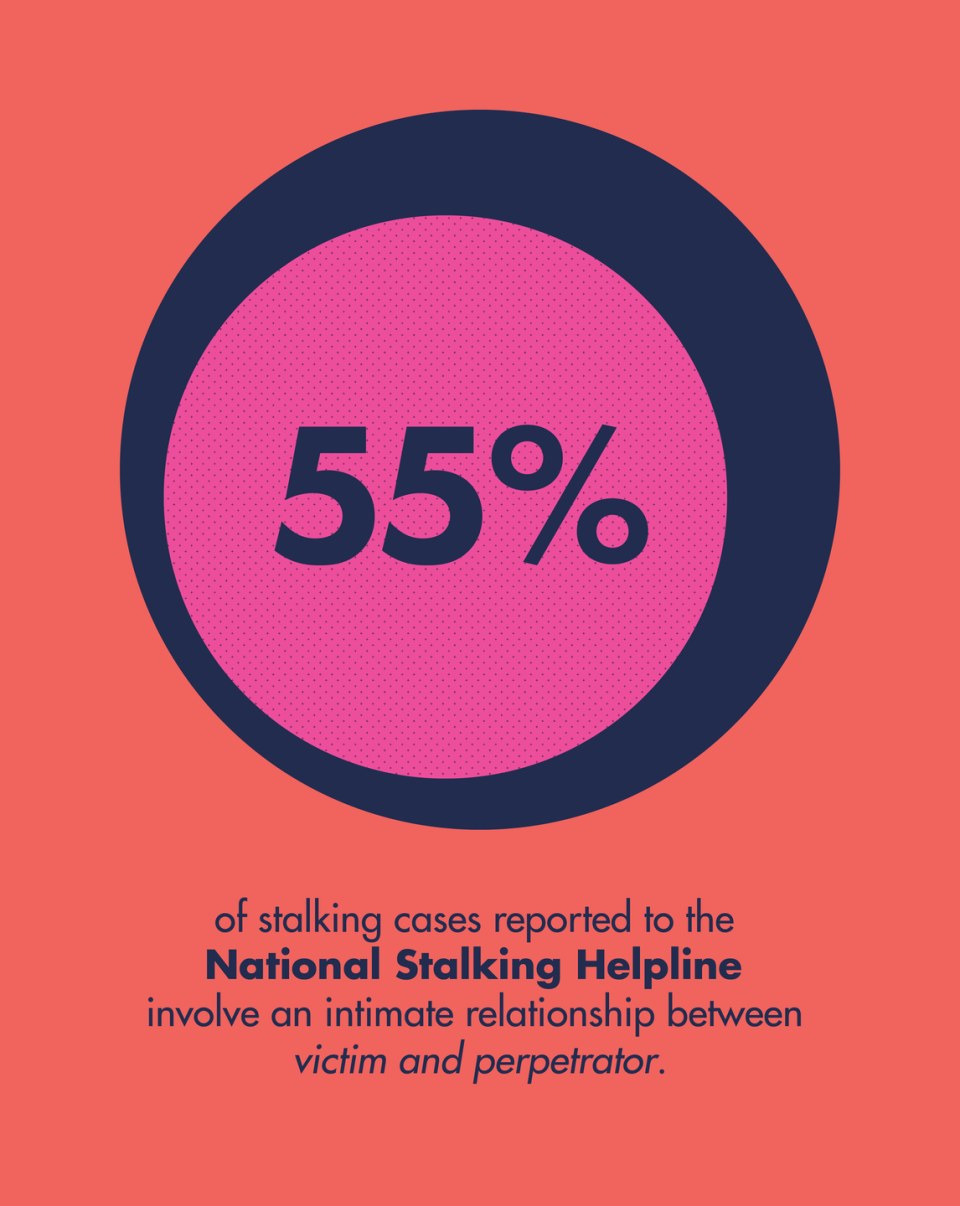

According to stalking charity Suzy Lamplugh Trust, in 55% of cases reported to the National Stalking Helpline, there has been an intimate relationship between victim and perpetrator. “Women are at the greatest risk of harm at the point of leaving a violent or controlling partner,” says specialist solicitor Rachel Horman-Brown. “That’s when rejected stalking can play out because the perpetrator realises they’ve lost control.” And one of the quickest ways to regain control? Technology. Stalkers can now invade their victims’ lives faster and more efficiently than ever before – as Greg knew. He had used his computer to hack into Layla’s emails on the night she left, and found the takeaway confirmation – complete with delivery address.

During lockdown, between March and June 2020, anti-virus platform Avast recorded an increase of 83% in the use of spying apps and stalkerware in the UK. Vehicle trackers can be bought online for as little as £21.99. Even without this software, the way we live our lives now – constantly plugged in, socialising through social media – means stalkers can easily keep tabs on victims. After blocking her stalker on Instagram hundreds of times, Hannah decided to abandon social media altogether. “The moment I set up an account, she finds

it and sends me messages,” she says.

Throughout his 18-month stalking campaign, Greg used technology in increasingly inventive ways, so Layla never knew what was coming next. He posed as her on a travel website and cancelled her holiday. He changed her Facebook password, locking her out. He took out bank cards in her name. And when she finally moved away for her safety, he tracked her down again and showed up in the dead of night, staring through her kitchen window.

“Hey, when do we go back after half-term?” When the Facebook message first popped up, Jasmine* politely replied, answering the question. It was 2008 and Adam*, an “outcast” from a few years above, who would tuck his long, greasy strands of hair behind his ears as he skulked around the playground alone, had begun messaging her. The pair had no mutual friends, and Jasmine – who was only in her second year of high school – had never spoken to him. When courteous, dismissive responses didn’t deter him, Jasmine began feeling uncomfortable about the incessant messaging, which gradually intensified over the years to an insistence that they were “meant to be together”, and an aggression at her rejection of his propositions. By the time she reached college, Jasmine hoped she could leave Adam and his obsessive online crusade behind.

When I caught up with Jasmine – 12 years after that first message from Adam – she was shaken. Just days before, on her first shift back in a shop after lockdown, a man in an oversized face mask and pulled-down beanie hat came into the store. With face masks now the norm, it initially sparked no alarm. But as the man peeled back his disguise and whispered, “Do you not recognise me, Jasmine?” a wave of panic engulfed her. She fled through a side exit, but Adam followed and grabbed her forcefully from behind. A police officer nearby ensured Jasmine made it home safely, but the torment continued. A few nights later, she woke to her phone buzzing, an unknown number flashing up. Deep, drawn-out breaths were all she could hear.

“I carry a rape alarm at all times,” Jasmine tells me over the phone, on a number she’s changed five times in as many years. “I’m petrified. I’m so on edge and I hate it.”

Jasmine first contacted the police in 2013, but it was only after Adam turned up at her work that they began to investigate. They found a password-protected document on his computer that listed her address, numerous phone numbers, friends and other personal details, alongside a catalogue of photographs. Yet, despite this evidence, they won’t charge him for stalking. Instead, he faces the lower-level charge of harassment. While Jasmine awaits the hearing, she remains fearful of what Adam might do next.

Hannah managed to get a restraining order against her stalker, but one week later she began to show up again, and the police did little to help. “I don’t think the restraining order was worth the paper it was written on,” she says. Hannah has endured so many incidents, but because she’s spoken to a different police officer every time, nothing seems to get logged. “They never link things together. To them, the individual incidents don’t sound like a big deal, but to me, this is four years of being followed.”

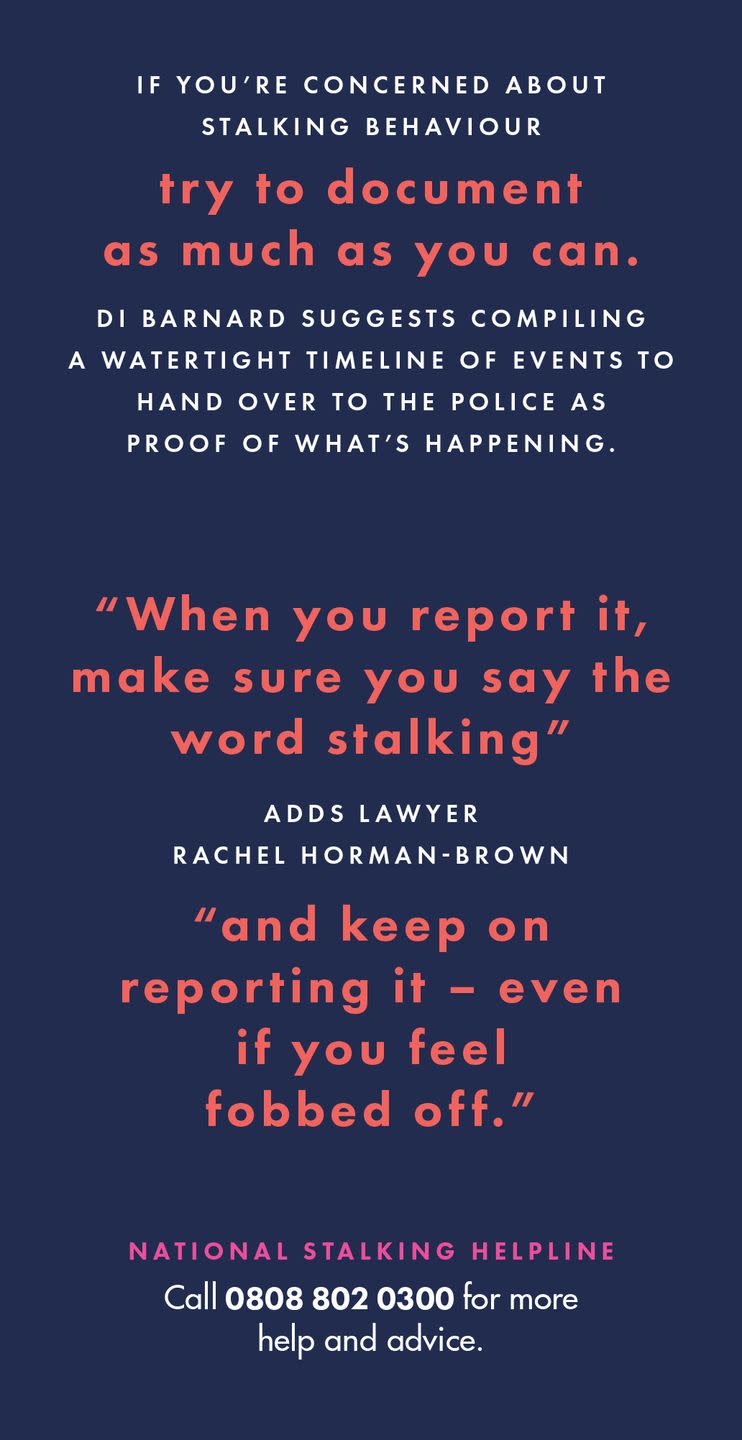

Here’s the thing: to prosecute someone for stalking, you only need two incidents to make it a “course of conduct” and constitute an offence. “There seems to be a misconception among some police that a threat of violence is required in order for it to be stalking,” lawyer Rachel Horman-Brown tells me. “But if it causes the victim serious alarm or distress, and has a significant impact on their day-to-day life, that’s sufficient for the most serious stalking charge, which is punishable by up to 10 years’ imprisonment.”

On paper it seems simple enough, but clearly that doesn’t match up with reality. The burden of proof in any crime lies with the prosecution, but with the victim being at the centre of the evidence in stalking cases (unlike, say, a burglary) it requires them to do the hard work gathering it. And even then it can be another battle entirely to get the police to take them seriously. “All along they’ve told me to get videos, take pictures, write a log. I did all these things and it still wasn’t enough,” Hannah says, as she prepares to move more than an hour away in a bid to put an end to the stalking herself.

“We continue to take stalking extremely seriously and are working closely with other statutory agencies and specialist support organisations to ensure that stalking victims are responded to appropriately and crimes are investigated,” says Deputy Chief Constable Paul Mills, the National Police Chiefs’ Council Lead for Stalking and Harassment Offences. “We would always urge anyone who believes they may be the subject of stalking to come forward at the earliest opportunity and report their concerns.”

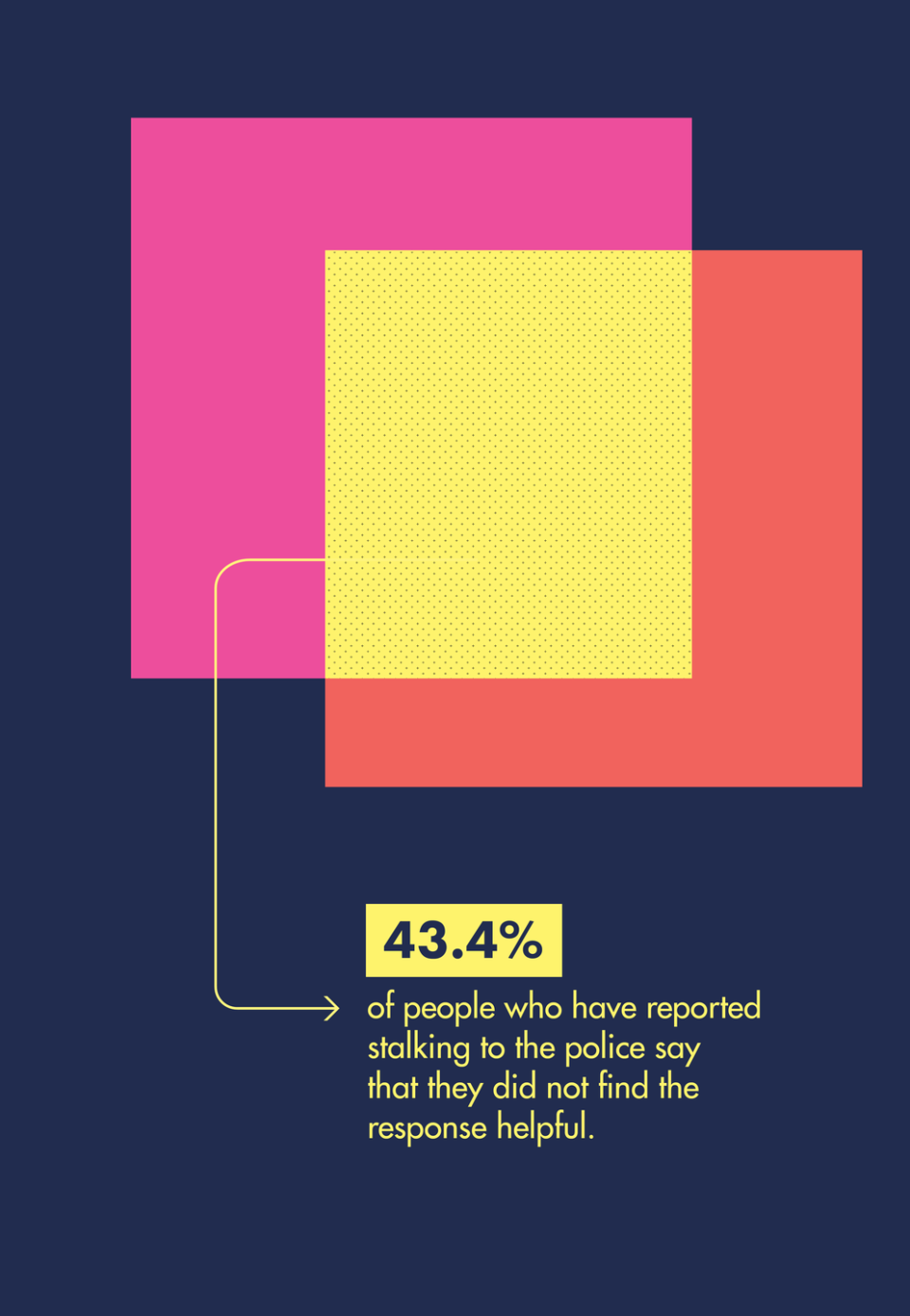

Despite this, Hannah’s experience isn’t unique; 43.4%of people who have reported stalking to the police say that they did not find the response helpful. Horman-Brown, who regularly deals with such cases, thinks she knows why. “My view is that, generally, the police seem to meet victims with disbelief from day one,” she says. “It’s an attitude problem.”

Detective Inspector Lee Barnard agrees. Having spent much of his policing career working in the Violence Against Women And Girls sector, and now heading up the policing side of London’s Stalking Threat Assessment Centre (STAC) – a specialist unit designed to tackle stalking using the combined force of mental health specialists, probation officers and victim advocacy experts from Suzy Lamplugh Trust – he’s seen this “attitude problem” first-hand. “Stalking [is an area] where, historically, our brightest and best haven’t always ended up. Sadly, they’re not seen as exciting units,” he says.

It’s possible that this problematic police disinterest stems from stalking being a relatively new social construct. California was the first territory to implement stalking laws internationally in 1990, but England and Wales didn’t follow until 1997. We’ve been slow on the uptake with legislation, but now it’s here, “stalking” doesn’t actually have a strict legal definition. If there were a specific list of behaviours that amounted to stalking, this could be “helpful in some ways”, says Clare Elcombe Webber, manager of the National Stalking Helpline. “But it also means, as technology advances and new capabilities evolve, that list would just get more and more out of date.”

Change does seem to be on the agenda. This year, the government introduced new Stalking Protection Orders that enable them to intervene more quickly and force perpetrators to undertake programmes for reform. If a new amendment to the Domestic Abuse Bill is passed, we would see serial stalkers and domestic abusers added to the Violent And Sexual Offender Register, giving police a greater understanding of immediate threats. Money is being spent on specialist, multi-agency stalking units, like the London-based STAC that DI Barnard works with, which – so far – looks to be effective. And training is readily available for staff, the National Police Chiefs’ Council tells me, albeit in the form of e-learning.

The value of adequately trained police officers is immeasurable, as Layla can attest. Following a complaint to her local force about the mishandling of her reports (one officer usefully suggested she “call Greg to ask what he had changed her Facebook password to”), she was given a specialist policewoman to handle her case. As a result, Greg is awaiting trial for the most serious stalking charge there is, and faces prison. “She’s a godsend,” Layla says of her officer. “She’s given me validation. I know I’m not crazy.”

Armed with a phone folder of screenshots for evidence, Joanne McLaren took her 23-year-old daughter, Molly, to the police station. It was June 2017 and Molly’s ex-boyfriend, Joshua Stimpson, had been stalking her for weeks. Police spoke to Stimpson, but they quickly let him go, finding nothing when they ran a check.

Unbeknown to Molly – and Kent Police at the time – stalking was a common pattern of behaviour for Stimpson. He had harassed a woman he’d been on one date with, before allegedly slashing her mum’s car tyres. Later he threatened her, saying he would follow her on holiday and drown her. The problem was that this had taken place in Staffordshire, and the local police force there did not fully investigate the incidents or record Stimpson as a suspect for a crime. As a result, officers on Molly’s case weren’t aware of exactly how dangerous Joshua Stimpson really was.

On 29th June 2017, Stimpson followed Molly to the gym. She left and returned to her car, but he fought open the door and launched a “frenzied” knife attack on her. Molly died from

her injuries at the scene.

After the murder, the police checked local camera footage and spotted Stimpson in the area several times in the days before – despite the fact that he didn’t live close by. If they had known to do these checks sooner, perhaps things could have been different. “If his previous record had been logged and Kent police could have found it, they might have acted a bit more rigorously,” Molly’s father, Doug McLaren, says. That painful “what if” is something Molly’s family now have to live with forever.

What happened to Jasmine – or Hannah, or Layla, or Molly – is not their fault. Far from it. But it’s troublingly easy to see how some victims are left regretting their own actions in the course of it all, instead of the entire blame resting rightly with those harassing them. “Something I’ve realised throughout all this,” Jasmine reflects towards the end of our conversation, “is that, as a woman, I’m used to men sending me unwanted messages on Facebook. So to begin with, I didn’t see it as serious. I wish I’d done more because it ended up stemming into this.”

Sadly, women may be used to harassment in everyday life, but we need to be able to recognise when enough is enough. And we deserve to feel protected when we do.

*Names have been changed

You Might Also Like