When Paul Simon bombed on Broadway: inside the humiliating Capeman disaster

In October 1996, in a rehearsal space at Westbeth Theatre Centre in New York’s Greenwich Village, folk icon Paul Simon picked up his tambourine and walked. He paced the room, watched by dozens of actors and musicians. Occasionally he would stop and rattle the instrument before tutting and moving on. Nobody dared breathe.

“He spent half an hour moving the tambourine around the room to see where it would sound best,” an eye-witness would later tell the New York Times. “He’s always looking for new things, exhausting the possibilities. And then he usually goes, 'Oh, I guess it was better the way we had it,'” added Oscar Hernandez, the Broadway musical director hired to help Simon bring his singular vision to the stage. “But until he goes through 18 million changes, he just doesn’t settle.”

Simon had refused to settle throughout his career. But while his perfectionist streak had been an asset in his days as a folkie, it was proving problematic in the collaborative world of musical theatre. In less than six months, Simon was to make his Broadway debut with The Capeman. The musical drew on his love for “Latin” music to tell the story of Salvador Agrón, a Puerto Rican juvenile delinquent convicted of murder who later became a celebrated Marxist poet and community activist.

A play about a convicted killer is a hard sell, even in the happiest circumstances. These were not happy circumstances. Simon’s resolve to tell the tale as he intended was causing all sorts of issues. The tambourine had to be perfect. And Simon wanted to do Broadway his way by writing the songs before nailing down the story. More than a few involved sensed disaster. How right they were.

Simon is today, at age 81, the grand old man of folk-pop. His 2018 farewell tour was a moving swan song. Last week he returned with Seven Psalms, his 15th studio LP and a record described as “a seven-part piece meant to be listened to in its entirety, and is a completely acoustic performance”. Where other artists of his generation are happy to milk the nostalgia circuit, he dares to push forward. In his eight-decade career as a writer, he continues to innovate.

A quarter of a century ago, that determination to always be on the front foot was almost his undoing. The Capeman, which opened and closed within a few weeks in the spring of 1998, was the great humiliation of Simon’s professional life. He toiled on it, on and off, for 10 years and put much of his own money into its reported $11 million budget. But the reviewers hated it, Broadway relished his demise, and it shuttered after a mere 28 performances.

And yet The Capeman was arguably ahead of its time. As a rock star plunging headfirst into musical theatre, Simon was laying the groundwork for U2, who would have their difficulties with Spider-Man: Turn Off The Dark, a cataclysmic super-hero musical with songs by Bono and The Edge which closed in 2014 after three years and losses estimated at $60 million.

But The Capeman also arguably foreshadowed the blockbusting hip-hop musical Hamilton: its story likewise tapped into the emigrant experience, and, as with Hamilton, it challenged Broadway with musical genres that went beyond traditional show tunes.

Its most profound impact was on Simon himself. He’d been in a midlife funk making The Capeman. By the late 1990s, he was in his 50s and eager not to become “the guy that plays Central Park” – another boomer getting rich on nostalgia.

He got his wish. Simon emerged from The Capeman a changed artist: his next album, 2000’s You’re The One, was Grammy-nominated and was the start of a remarkable late career streak that also included the top 10 2011 LP So Beautiful or So What and his 2016 UK number one, Stranger to Stranger. He was on the rebound – and the thing he was rebounding from was The Capeman. It was a disaster. But perhaps it was also when Simon fell back in love with the troubadour’s life.

Simon had been a scrappy teenager trying to break into the New York folk circuit when, in 1959, Agrón and a companion stabbed two random kids at a playground in Hell’s Kitchen. The killers had been part of an East Harlem gang, The Vampires, and Agrón had dressed the part, wearing a long cape trimmed with red.

“He was described as this tall Puerto Rican with a cape. His companion had an umbrella. They killed two boys,” Simon would recall shortly before the curtain went up on The Capeman. “The newspaper called them the Capeman and the Umbrellaman. It was a big story. Front of all the papers for about a week.”

For 30 years, Simon forgot all about The Capeman. Then, in 1989, Agrón popped into his head. The former Capeman had become a poet in prison and, on his release after 20 years, worked as a youth counsellor speaking out against gang violence before dying in 1986 aged 42. Out of the blue, it occurred to Simon that his story might make for a Broadway musical.

He worked for years on the songs that would become The Capeman. “The idea came just like that. It’s from the Fifties – there’s doo-wop,” he said, referring to the popular rhythm and blues genre with which he had grown up in Fifties Queens. “Latin music in conjunction with doo-wop is a nice sound. Why don’t I research this and see where it leads?”

Where it led to was the door of Saint Lucian poet Derek Walcott, the Nobel prize winner whose work Simon had discovered while recording his 1990 album Rhythm of the Saints in Brazil. He and Walcott agreed The Capeman should be a story of sin and redemption – and should pose the question of whether it was ever possible to wash away the stain of a wicked deed. Musically, it would draw on the music of Agrón’s native Puerto Rico – plus the blues, doo-wop and even the Yoruba music from West Africa, of which Simon was a fan.

“This is not a very forgiving society we live in now,” said Simon. “We’re a very religious country. We’re not a very forgiving country. How can you achieve or attain redemption? Is it a possibility?”

“I don’t think I would have worked with anybody but Paul Simon,’” Walcott would tell the New York Times. “Before I met him, I always thought he was a very fine poet. I mean, the first line of Graceland is a great line of verse: “The Mississippi Delta was shining like a National guitar/ I am following the river down a highway through the cradle of the Civil War.” That’s Whitmanesque.”

In Walcott, Simon had that rare collaborator for whom he had complete respect and could treat as an equal. And yet, they didn’t always see eye to eye. “Derek would want to write a poem or lyric and set it to music,” Simon said. “I had to say: “No, first comes the sound”.

Simon’s insistence that the textures of the songs take priority meant that the lyrics had a trite, cobbled-together quality. Consider early number Born In Puerto Rico. “I was born in Puerto Rico/We came here when I was a child,” begins the rolling Latin ballad. “Before I reached the age of 16/I was running with the gang, and we were wild.” Stephen Sondheim had little to worry about.

Not so merrily, they rolled along. Simon next reached out to James Nederlander Jr., the Broadway promoter who agreed to help raise the estimated $10 million budget. Again, Simon’s determination to do things his way became an obstacle. Nederlander arranged for Simon to meet Dodger Productions, a successful Broadway production company. They told Simon to hire a director without getting bogged down in the music.

“I said, “What you’re telling me is that I don’t know what I’m doing,’” Simon recollected. “And while I’m still in the creative process, that’s harmful.”

Simon eventually hired a director, Argentina-born Susana Tubert – only to fire her because she didn’t “click” (she felt Simon and Walcott had “hoarded” the script.) “I thought Susana would have had an edge, being a woman and from South America,” Simon revealed to the New York Times, “but it was obvious that we were going to have to keep having meetings about what we really meant, and it was better to do it sooner than later.”

Here was the point at which Simon and Walcott and choreographer Mark Morris, who was appointed director, gathered in Greenwich Village for rehearsals. The clock was ticking, the budget ballooning and Simon was bogged in the minutiae of where the tambourine sounded best.

As he rambled in the weeds, the financiers sweated. Nederlander reduced his commitment to $1 million, and other backers pulled out. Three weeks before opening night, Broadway veterans Jerry Zaks and Joey McKneely entered stage left to knock the production into shape.

The challenge proved beyond even their talents. The Capeman opened in January 1998 to scathing reviews (though it subsequently received three Tony Awards, including one for Best Original Score). “The Capeman has been a labour of intense devotion for Simon,” said the New York Times, “It’s like watching a mortally wounded animal. You worry that it has to suffer and that there’s nothing you can do about it.”

“West Side Story particularised, de-prettified and de-balleticized. A tough call for entertainment,” agreed the New York Post, though the review did praise Simon’s “bewitching” score and Latin pop star Marc Anthony as the young Agrón.

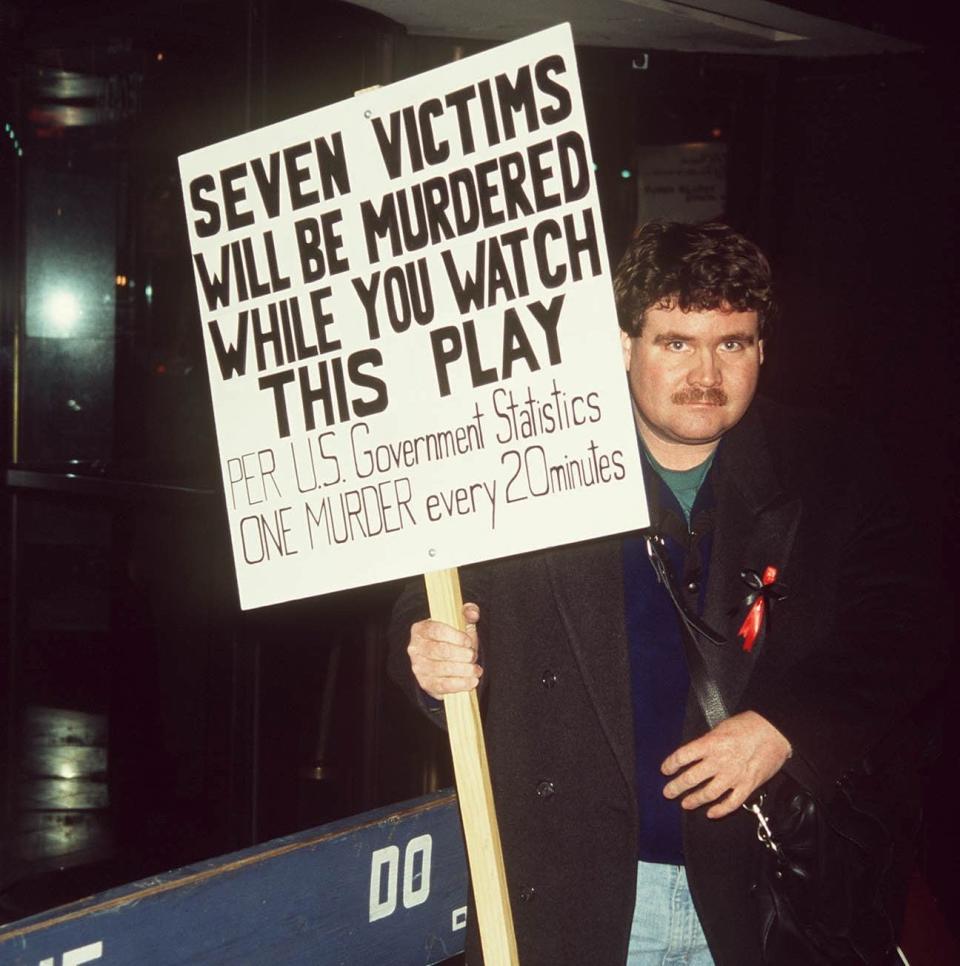

Harsh reviews were the least of Simons’s problems. Opening night at the Marquis Theatre was picketed by families who had lost loved ones to gang violence. They saw The Capeman not as an exploration of sin and forgiveness but as a love letter to a murderer. “Remember the Victims, Remember our Children,” said one sign. “Our Loss Is $imon’s Gain,” said another.

“My cousin’s murder should not be entertained. There are a million stories in New York City; why pick this one? You don’t do a murder musical to jump-start your career,” one picketer told the Associated Press. “Would Paul Simon do this if his son was murdered?”

She added that she “was not trying to shut Paul Simon down”. Never mind, Broadway was happy to do it on her behalf. Simon’s belief that he knew better than Broadway had not gone down well – and when the play shuttered in March, amid mounting losses and tiny audiences, few tears were shed.

“Normally in the theatre community, people feel bad when they see someone else whose production has failed,” said Rocco Landesman, president of Jujamcyn Theaters. “But I think there is a feeling about Paul Simon that it couldn’t happen to a nicer guy.”