'Are we together or are we ain’t?': the night James Brown stopped Boston from burning to the ground

They were just kids, and under the spotlights at Boston Garden they looked startled and unsure of themselves. But to the armed cops charging from the wings the stage invaders represented a clear-and-present threat to the peace, justice and the American way of life. A terrifying hush descended as the police stomped on and the young men who’d swarmed up from the floor tensed. Violence seemed imminent.

But then James Brown, Godfather of Soul, made his way forward and waved away the riot squad. “Wait a minute, wait a minute now WAIT!” Brown told the dozen or more audience members who had rushed his show in downtown Boston. “Step down, now, be a gentleman….Now I asked the police to step back, because I think I can get some respect from my own people.”

With his intervention, the atmosphere changed. The interlopers rejoined the audience, the police retreated. By putting himself in the literal firing line Brown faced down a potential riot and saved lives. He had, at a moment when the stakes had never been higher, stepped up and provided leadership.

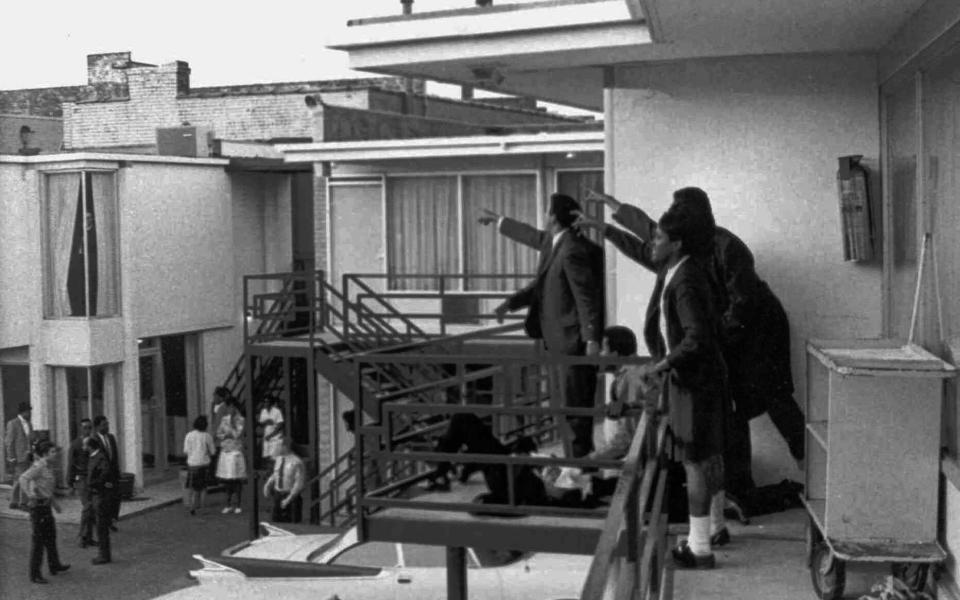

It was April 5 1968 and all across America flames were rising into the night sky, accompanied by the squall of sirens and the sound of gunshots. On April 4 Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King had been shot dead, at the age of just 39, by white supremacist James Earl Ray. Horror and grief had led to protests and then to violence in New York, Atlanta, Los Angeles, Washington DC and elsewhere.

Today, as America is engulfed by protests, riots and looting following the killing by Minneapolis police of George Floyd, footage of the 1968 unrest feels eerily familiar. Then as now marginalised communities took to the streets to protest and the police cracked down viciously. As the situation escalated, so the cities burned.

This obviously places prominent African-Americans in a difficult position. Rapper Killer Mike this week drew praise and criticism in equal measure for an impassioned speech delivered live on American TV.

“I woke up wanting to see the world burn down yesterday because I'm tired of seeing black men die,” he said. “But we have to be better than this moment. We have to be better than burning down our own homes.”

Mike, to some, represented a voice of reason in a world gone mad. Others noted that he is himself the son of an Atlanta police officer and suggested he was thus incapable of objectively discussing police violence.

“Killer Mike is a millionaire from a police family who raps about killing cops for money and then cries when people in his city rise up against the police,” went one Tweet.

🙄 a sellout ... until it comes to his city. @KillerMike https://t.co/qhNejBmUsa

— RbW008 (@playbirdiegolf) May 31, 2020

“We ALL watched Killer Mike and [fellow rapper]TI stand at that EXACT SAME PODIUM and gloss over police terrorism in ATL and make it seem like Atlanta is “Wakanda.”,” said another. “Two days later ATL cops are caught on camera terrorising Black folks and all they get is desk duty and fired?”

Some 50 years earlier, Brown was likewise caught between opposing forces. He’d always admired Martin Luther King, though he had disagreed with King’s policy of non-violent resistance.

But Brown was in many ways reflexively conservative – a proud American who would endorse Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan for the Presidency (and in 1993 would sing happy birthday to his friend, the notorious white supremacist politician Strom Thurmond).

Moreover, as with the basketball star Michael Jordan, a generation later, he tended to avoid politics for fear of alienating a mainstream audience. This had brought him to the attention of the Black Panthers, who condemned him as a “capitalist”.

Still, Brown, then aged 34, was deeply shaken when on April 5 he boarded his personal Lear Jet and took off for Boston’s Logan Airport for that evening’s concert at the 14,000-capacity Boston Garden. He and Martin Luther King hadn’t been friendly. But they’d met on several occasions and Brown was numbed by the assassination.

As his plane soared towards Massachusetts, though, little could he have suspected the fierce debate taking place below. As was the case in most other American cities, Boston’s African-American community lived in segregated poverty. Largely confined to the distant suburbs of Roxbury, three miles from downtown , they existed apart from the city’s white population.

The calculation was that, if they rioted, they would do so in their own streets. For the rest of Boston life would carry on as normal. But then it was pointed out to recently-elected Boston Mayor Kevin White that Brown was booked to play that night at Boston Garden, bang in the middle of town.

“His concert might bring 20,000 black people into the city,” White would say. “It had too much emotion in it.”

“They didn’t appear to be all that concerned about the rioting as long as it was happening in Roxbury,“ said Robert Hall, professor of African American Studies and History at Northeastern University in Boston. “They cordoned off the riot here and let it happen.”

White was a liberal Democrat who supported the racial integration of schools in Massachusetts (hugely controversial at the time). But he was still a privileged white person who knew little of African-American culture. When he heard Brown was coming to town, for instance, he thought it was former football star Jim Brown.

His first instinct was to call off the show. He was talked out of doing so by Tom Atkins, Boston’s only African-American councilman : “You can't cancel the James Brown show because if you do that, you're going to have 14,000 kids showing up at the Boston Garden finding out by a piece of paper stuck on the door that the show has been canceled,” Atkins was quoted as saying in James Sullivan’s The Hardest Working Man: How James Brown Saved the Soul of America.

“If they're not already angry and distraught over the murder of Dr. King,” Atkins continued, “Now they're really going to be mad.”

Instead of cancelling, it was suggested the concert be aired live on local television. The calculation was that people who might otherwise have taken to the streets would instead stay at home and watch Brown. White was persuaded and the WGBH public service agreed to carry the show at short notice. Now all they had to do was convince James Brown.

As he touched down at Logan, Brown may have been surprised to find Tom Atkins waiting at arrivals. On the drive into Boston, the councilman made his pitch about showing the concert on air. Brown reacted with fury. Reports were already reaching him of concert-goers returning to the venue for refunds.

“If you put the show on TV for free, who's going to come?” he said. “I’ll do it if the city government can promise me some money.'”

“The city arranged to televise his concert without his consent and he was losing tens of thousands of dollars through people returning tickets so they could watch at home free,” said David Leaf, director of the 2008 documentary The Night James Brown Saved Boston, explained.

“In those days it wasn’t easy for African American headliners to find a place in Boston, and now the mayor of Boston was practically begging a black man for help,” he told Wax Poetics.

Brown’s demand was $60,000, at which White and the council blanched (Brown’s manager would state they were in the end paid just $10,000). Atkins pointed out that if rioting broke out in Boston, as it had across the rest of America, the cost to the city would be considerably higher.

The singer later claimed money wasn’t a consideration. “Even though I was going to take a financial bath I knew I had to go on and keep the peace,” he wrote in his 2005 memoir I Feel Good: A Memoir of a Life Of Soul. “There are some things more important than money.”

But other accounts have it that Brown continued holding out. WGBH only received final confirmation that the broadcast was going ahead three hours before he was due on stage.

And Brown had been correct. Fans did stay away. In the end only 1,500 filed into the 14,000-capacity venue. Some had decided to watch at home. Others stayed away fearing the show would dissolve into a riot.

“Major dread, major dread that day,” David Gates, a white devotee of James Brown, told Leaf in his documentary. “Should we go, should we not go…? That’s a victory for the bad guys if every white person stays away.”

Brown kept his word, though, and, an hour before he was due on, arrived at Boston Garden. There to greet him was Mayor White. “I never met any thing like James Brown. I never saw any thing like James Brown,” he would reflect. “Man, he was a piece of work.”

But if he’d turned up, Brown was in no hurry to take to the stage. The broadcast began yet there was no sign of the headliner. Forty minutes passed, during which WGGBH was required to fill the airtime with inane commentary.

Finally, Brown and his band trooped on. Backstage he’d been agitated about money. His band meanwhile had feared somebody might try to shoot him – perhaps a white supremacist seeking to emulate James Earl Ray.

Yet as soon the curtain went up, a switch flipped. Brown was suddenly, irresistibly larger than life. This was clear when Kevin White came on and the MC made to introduce him.

“Just let me say, I had the pleasure of meeting him,” interjected Brown, grabbing the microphone from the announcer. “And I said “Honourable Mayor,” and he said, “Look, man, just call me Kevin.” And look, this is a swinging cat Okay, yeah, give him a big round of applause, ladies and gentlemen. He’s a swinging cat.”

Twelve hours previously he had been completely unaware of the existence of Mayor White. Now he was talking about him as if they had been life-long friends. Brown proceeded to charged through his set, swivelling, snarling and sweating in that trademark fashion.

In the largely empty room, the atmosphere turned increasingly ebullient. And all across Boston people, black and white, stayed at home glued to their sets.

As the end loomed, Brown launched into I Can’t Stand Myself (When You Touch Me). Suddenly a young black man tried to jump up. A cop appeared from nowhere and shoved him off. In response a group of teenager invaded the stage. More police arrived. The band stopped. Everything – the show, Boston, maybe even Brown’s career – was on a knife edge

“I’m all right, I’m all right” said the singer, indicating to the police that they should retreat. “I want to shake their hands.”

With the cops exiting, he addressed the stage-invaders. “We are black! Don’t make us all look bad! Let me finish the show,” he said. “You’re not being fair to yourself or me or your race. Now I asked the police to step back because I thought I could get some respect from my own people. It don’t make sense. Are we together or are we ain’t?”

They heard his words and left and the performance resumed. In the wings, Kevin White got on the phone to WGBH: could they repeat the broadcast in full at 11pm? They did and in Boston, the evening went off largely peacefully.

For Brown, the night changed everything. A few days later, the Mayor of Washington called on him to speak out against rioting, which he was happy to do. The following month, he attended a White House state dinner. And he fulfilled his promise to perform for American troops in Vietnam.

“In Augusta Georgia, I used to shine shoes outside a radio station,” Brown said in Washington. “Today I own that radio station. You know what that is? That’s black power. I’m talking from experience: let’s live for our country, let’s live for ourselves.”

These gestures were not universally welcomed by the African-American community. As with Killer Mike’s speech some perceived a black man taking a position of leadership. Others saw someone pandering to the status quo. Brown, though, was in no doubt where he stood – and that August poured his feelings into his new single, Say It Loud I’m Black and I’m Proud.

“There was only one man who could make America stand still and think and that was a man who didn’t have a PhD from Boston University like Dr King,” civil rights activist Al Sharpton told Leaf in The Night James Brown Saved Boston.

“He was a man who knew how to express the utterances and the screams and the feelings of a whole people…If anyone understands what we feel, it’s James Brown.”