Murder in Mayfair, review: trial by television made necessary by diplomatic failure

Many home movies capture the inconsequential moments in innocent young lives. No parent wielding a camera can imagine that lovingly shot footage of a child will one day meet the darker needs of true crime. Such was the fate of a clip showing a sweet blonde girl with gap teeth mucking about by a Norwegian lake in the 1990s: her father would one day hand it over to the makers of This World: Murder in Mayfair (BBC Two).

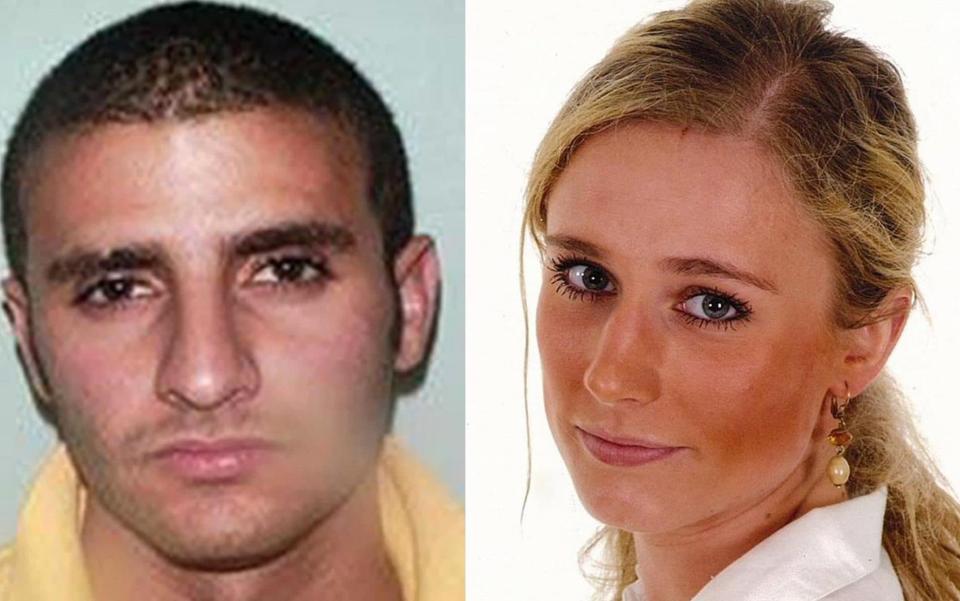

On 14 March 2008, the body of Martine Vik Magnussen was found under rubble in a basement in central London. She had been raped and, by compression of the neck, murdered. The only suspect – fellow business student Farouk Abdulhak – had already fled home to Yemen, which has no extradition treaty with the UK and where he was assured of protection: his father, a well-connected arms dealer so rich he was the only Yemeni with a private plane, refused to hand over his son to “a country where I don’t know who their god is”.

Abdulhak is still there and Murder in Mayfair offered no hint that he will ever stand trial in an English court. So in one sense this was a report without a true denouement, or the possibility of one. Instead it was something else: a portrait of grief, a story about journalism, and finally a trial – for lack of any other means – by television as Abdulhak, never before interviewed by the police or a journalist, answered questions and admitted his involvement for the first time.

Martine’s father, Odd Petter Magnussen, was the only family member to speak on film. Unflinchingly he described the feeling of learning that his daughter had died as “nearly physically to be ripped apart”. And seeing her laid out in the mortuary: “That is a situation beyond comprehension really. I couldn’t leave Martine. I just couldn’t leave her.”

In a sense he still can’t, and won’t until death, or until justice has been served. More than any of the UK authorities, Magnusson's best ally has been London-based Yemeni journalist Nawal Al-Maghafi, who made contact with him in 2011. Threatened by the Yemeni state, she got nowhere when trying to coax Abdulhak from his foxhole. Then war came to Yemen and, marooned in a city held by Houthi rebels, Abdulhak’s protective wall crumbled. Last year, when Al-Maghafi contacted Abdulhak on Snapchat, where he styles himself as “Yemeni Dude”, it was as if he had been waiting.

While their shared nationality evidently assisted Al-Maghafi, it was also clear that Abdulhak was more prepared to communicate with a woman who presented herself as a neutral non-threat. Only when they spoke over the phone, and his self-deluding evasions piled up, did she start to challenge his narrative.

The psychological profile she managed to draw up was of a self-pitying monster, devoid of empathy, who cared only for his own well-being and felt nothing for his victim’s family. “I don’t know what answers they’re going to get,” he mused. “Nothing’s going to bring their daughter back.” He terminated one call because he was feeling “uncomfortable”, postponed a face-to-face interview when Al-Maghafi flew to Yemen because he was “too shy and too nervous”, and eventually, denying murder, dismissed Martine’s death as “just an accident, nothing nefarious, a sex accident gone wrong”. On screen it was even grimmer than it sounds.

Television as an instrument of inquiry did its best. It got a story, and filmed itself doing so. But it’s difficult to know what lesson to take from it. Does Abdulhak’s casual cruelty tell us anything more widely about toxic masculinity? All that’s left is waste, and home movies sapped of all joy. “Martine,” said a friend filming their girl gang in 2008, “I’m going to show this movie when we’re old, fifty and frail.” That gang, three Norwegians now in their late thirties, reunited on a sofa to remember a woman who didn’t make it past 23.