The mother who fell out with her son for writing about his drug abuse has done it again – in a novel

The narrator of Julie Myerson’s stark new novel keeps needling away at the moments when she feels she let her daughter down. The time when while away for work, she told her daughter when she rang that she’d call her back tomorrow, even though her daughter was clearly in distress. The time when she had an affair, which for a short period catastrophically impacted on family life. The time when she looks at her daughter, whose shoes are flecked with vomit, and can’t “see anything there to love or even to like”. And the time when she wrote a book about her child’s addiction to skunk, an addiction so bad she and her husband kicked the child out and changed the locks. Except the narrator, who is also a novelist, doesn’t mention this one.

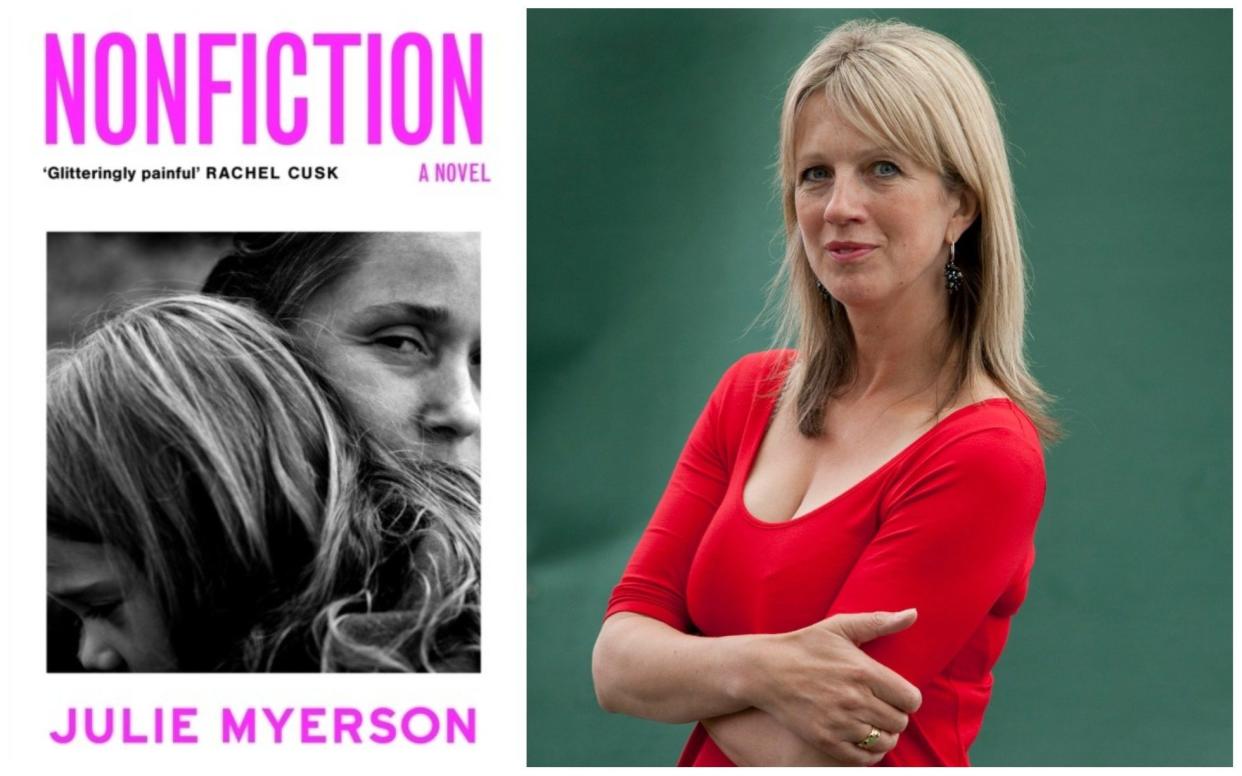

Novels are, or ought to be, distinct unto themselves, but Myerson is fully aware it’s almost impossible for Nonfiction, about a married couple struggling with their only child’s spiralling heroin addiction, to be read apart from her 2009 nonfiction book The Lost Child, in which Myerson detailed her son Jake’s crippling addiction to cannabis. Jake publicly objected that he never gave permission; Myerson – at the time a considerably more high-profile figure than she is now – was vilified in some quarters as a mother who had exploited her child’s private life in the name of her career. All the same, while Nonfiction reads on one level as a writer defending the right to write what she likes in whichever way she pleases, its knowing proximity to real life is also unavoidable: one quick internet search reveals that Jake did indeed briefly succumb to heroin addiction shortly after The Lost Child was published.

Still, the real question Myerson is implicitly insisting on with her title is whether Nonfiction can stand alone as a work of fiction. Certainly its territory is pretty harrowing. The daughter steals, lies and once hits the narrator so hard she is forced to go to A and E. When her parents refuse to give her money she goads them with stories of prostitution to fund her habit. She goes to rehab, relapses, and disappears for weeks on end. Throughout, the narrator mourns the baby teeth she used to brush that are now decayed and brown and struggles with what it means as a mother to be so unable to help a desperate child. At the same time her poisonous relationship with her own mother – the latter refuses to offer useful support and cuts her out of her will – provides a warped, inverted sort of mirror. Pointedly perhaps, or at least one can’t help but notice this, the narrator never once blames her mother for being the way she is.

Yet Nonfiction also feels locked in a baleful quest for significance. It’s delivered in an uncompromising second person singular, which can be a powerful animating narrative tool but which here sometimes feels disingenuously performative. The prose is featureless and insistent, like strip lighting, yet the effect varies from the unrepentantly bland – “They are difficult days. Just getting from one moment to the next is a struggle” – to the dissembling trick beloved of autofiction in which an awful lot is supposedly implied by sentences that literally convey very little. “He asks me what I’m thinking. I tell him I’m not thinking anything.” The writer Rachel Cusk, who was also pilloried for straying from the path of accepted maternal behaviour in her 2001 memoir A Life’s Work, feels like an unofficial referential framework throughout, both stylistically – Myerson’s prose resembles a watered down version of Cusk’s elegantly distilled clarity – and in terms of substance: there are distinctly Cuskian moments when the narrator, like the narrator in Cusk’s acclaimed Outline trilogy, attends literary festivals and fixates on incidental encounters with strangers.

Such moments also allow Myerson to shoehorn in stagy conversations about novels and autobiography and how it’s assumed that female novelists will draw on their personal lives in ways that men do not, and are then attacked for doing so. But these are well worn, increasingly tired arguments. What I couldn’t get over was how little I actually cared about the novel’s blood and guts; the unfolding tragedy at its centre. Why, you wonder, did she even write it? One only hopes that now she has, this whole sorry saga has fully run its course.

Nonfiction is published by Corsair at £16.99. To order your copy call 0844 871 1514 or visit Telegraph Books