More than just a miniskirt: Two exhibitions reveal how Mary Quant shaped our world

If you’re a British woman, you’ve probably got Mary Quant in your wardrobe. OK, maybe not literally – but if there’s a sleeveless shift or a tunic dress, a Peter Pan collar or a skinny-rib sweater, a pair of brightly coloured tights or even a PVC raincoat, you’re wearing Quant. And that’s before mentioning her most famous creation: the miniskirt.

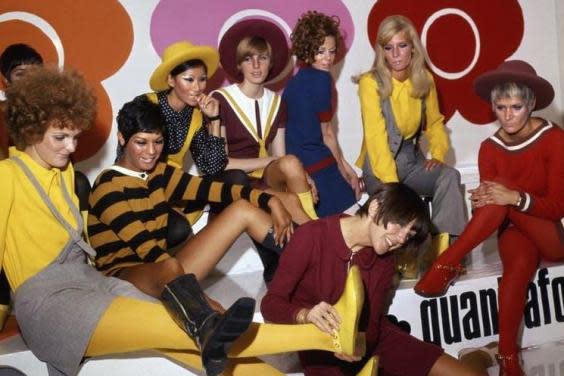

She pioneered mass-market, trend-led clothing – but the looks Quant came up with have proved anything but throwaway, still influencing both high end and high street fashion more than 60 years after she opened her first boutique. And in 2019, her creative vision and enduring influence is being recognised by two new museum shows.

This spring, the V&A opens a major exhibition of her work, with more than 200 garments and accessories, including previously unseen gems from Quant’s own archive. But first, Swinging London: A Lifestyle Revolution opens at the Fashion and Textile Museum in London. It uses Quant, and designer Terence Conran, as a way into looking at the “youth quake” that shook London in the late Fifties and early Sixties, which transformed the way we live. It features rare and early designs by Quant and Conran, plus clothing, textiles, furniture, lighting and homeware by fellow members of the “Chelsea set”, the bohemian west London crowd they ran with.

Quant changed how the world looked. Her vision – her use of shape, and of colour; her choice of material, and of model – really did define an era. When someone says to you “Swinging Sixties”, you might hear The Beatles, but you see Quant. Sure, her work is not (usually) to be found hanging in a gallery, but it would be wrong to underestimate the aesthetic impact of her designs. That two shows in one year are staging exhibitions of her work is surely testament to that.

There was a time when putting a Fifties frock on a pedestal and inviting serious contemplation of it as a work of art would have been sneered at. Still is in some quarters. But such cultural snobbery is increasingly being swept away. The decorative arts, long dismissed as feminine fripperies, are beginning to get their dues: museums and art galleries host shows looking at fashion, furniture, and textiles, from Anni Albers at the Tate Modern to the Dior exhibition at the V&A. And these not only celebrate artistry and innovation, but they also explore what decorative arts can tell us about their social moment and historical context.

“People don’t really want to even call them ‘decorative arts’ any more – it sounds less important than it is,” Dennis Nothdruft, head of exhibitions at the Fashion and Textile Museum, points out. Swinging London, he adds, is dealing with the big stuff: “It’s really a show about a group of people who changed how people lived their lives. There was a real shift in how people wanted to live after the war – and a new generation came up with new ideas.”

In fashion, the woman with the ideas was Quant. And her gender was surely key to her success: in an era of the pill and women’s lib, her clothes did their bit. True, hotpants may not seem the most generous invention for the average woman, but her tunics, pinafores and jumper dresses were practical and easy to wear, freeing the female form – and certainly a far cry from the hobble skirts and wasp waists of the 1950s and Dior’s New Look. Hemlines may have eventually reached unforgiving heights, but even being allowed to get your legs out was something of a liberation.

“Necessity wasn’t the mother of invention, fun was,” observes Quant’s son, Orlando Plunket Greene, in an introduction to the V&A show’s catalogue. “Across Britain a generation decided to risk it; go for it and have fun, unleashing an attitude revolution that changed much more than fashion.”

This revolution was, in part, economic: with the advent of mass production, stylish homeware and clothing could become widely available and affordable to all. Quant embraced that – famously claiming that “snobbery has gone out of fashion and in our shops you will find duchesses jostling with typists to buy the same dress”.

Quant began her business with exclusive boutiques, but as the Sixties began to swing, she launched the more affordable Ginger Group. While today mass production might feel uneasily synonymous with landfill and waste, in 1963 it was a revelation. Mary Quant became a global brand, its logo – a single daisy; very flower-power – becoming instantly recognisable.

“There was a point where Mary Quant could have continued making more and more expensive clothing but she really wanted to make things more accessible,” says Nothdruft. “She made a conscious decision.” Quant, from 1964, even sold paper patterns for her designs, so that women could make their own versions; the most popular sold over 70,000 copies.

Quant was born in 1934 in London. Her parents were hard-working schoolteachers who felt there was “no future in studying fashion”. Quant studied illustration at Goldsmiths instead – where she met her future husband and business partner, Alexander Plunket Greene, who hailed from a rather eccentric aristocratic family. After they met fellow Chelsea set member Archie McNair, who brought legal and business nous, the three started a company.

In November 1955, their fashion boutique Bazaar opened on the King’s Road in Chelsea. Quant initially thought they’d stock other designers – but could find almost nothing she actually liked. So she made the clothes herself. “I brought Butterick paper patterns and cut out pieces where I didn’t want them and added more paper where I did,” Quant is quoted in the catalogue to Swinging London as saying. “I brought the materials from Harrods as no one had told me about buying cloth wholesale.”

This may have been an extremely poor business model but it did at least result in unique, quirky looks. Her early designs were radically plain, often made using practical fabrics such as denim and tweed (the synthetics of the space age come later). And they took off, Quant attracting admiring customers and plenty of press attention.

Quant not only created the look of Swinging London, she also embodied it: the ultimate Chelsea Girl, young and hip, slim and gamine, she became a celebrity in her own right. When she visited New York in 1960, Life magazine dubbed Quant and her husband “exponents of elegantly way out ways both in clothes and behaviour”.

That visit was important for more than her burgeoning profile, however: it was where Quant and Plunket Greene first learnt about mass production techniques that were accurate in a range of sizes. On their return to England they launched the ready-to-wear Ginger Group line. And then, they sold it back to America: Quant’s clothing took off there, picked up by chain store JC Penney. Global domination beckoned.

Bright colours, clean lines, short skirts, shiny boots… as the Quant look developed, it continued to move with its era. New synthetic materials were put to inventive use, while art and design trends found their way onto the body. In 1963 Quant launched her “Wet collection”, featuring op art-inspired PVC raincoats. Swirling floral patterns bridged the gap between Liberty prints and psychedelia (as seen in the Quant poppy print worn by Jane Asher in 1966’s Alfie).

And while Quant was the perfect face of the brand, she also tapped into – or shaped – the zeitgeist with her choice of models. Jean Shrimpton, Grace Coddington, and Twiggy were a new type of fashion girl, all long legs and made-up doe eyes. They may not seem all that relatable today, but at the time such models, with their loose hair and more natural poses, seemed positively girl-next-door compared to the composed and lacquered fashion shoots that had been de rigueur.

Quant also branched out into makeup, with cutesy product names that sound like they could be used by Benefit products today – Cry, Baby waterproof mascara and Bring Back the Lash! fake eyelashes. All were emblazoned with her daisy logo. She’d later move into homewares and interiors too, an early example of a fashion label becoming a 360-degree lifestyle brand. Although her influence in the fashion world waned from the Seventies onwards, the brand endured: she licensed everything from Quant carpets to Quant cars, designing the interior of a Mini in 1988.

Quant was awarded an OBE in 1966; almost 50 years later, she was made a dame. And no wonder: as much as any fine artist, Quant’s approach to colour, pattern and structure epitomised an era. She shaped how we make and market fashion, how we buy and wear clothes – not to mention how much thigh we think it’s acceptable to flash. Diving into the archives of her work at the Fashion and Textile Museum, or at the V&A, will no doubt transport the visitor to Swinging London in its Sixties glory. But the real revelation surely is just how daisy-fresh many of these designs seem today.

Swinging London: A Lifestyle Revolution is at the Fashion and Textile Museum, 8 February to 2 June (ftmlondon.org); Mary Quant is at the V&A 6 April till 16 Feb 2020